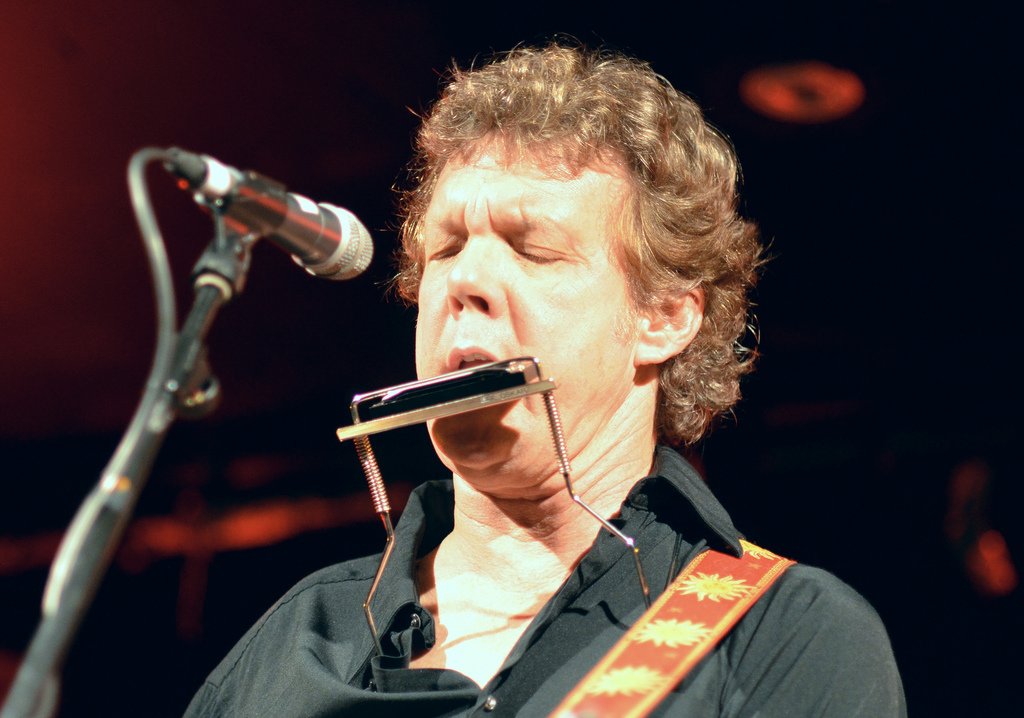

American folk veteran Steve Forbert: “I don’t care to sit down”

Photo credit: Sean Rowe

It was at the dawn of my teen years that my dad first handed me a copy of Jackrabbit Slim, the 1979 second album from American folk singer Steve Forbert, gifted him by a friend. With that began the longest unbroken period I, now 24, have yet spent listening to any artist, and a habit that survived untroubled through an adolescence otherwise dominated by heavy metal. I can vouch that it is an education to discover a musician who becomes one’s ‘own’. It allows space to explore their back catalogue at one’s own pace, to think about their songs for oneself, to feel that humorous lyrics are a private joke, insightful ones part of an ongoing conversation.

I meet Forbert outside Nell’s Jazz and Blues, Hammersmith, where he will play the London leg of his most recent European tour. I don’t notice him approaching, and it is an odd sensation to be so immediately face-to-face with a man who has only ever gazed out from successive CD covers, ageing 35 years as I aged 12.

We sit down in the green room, and he sits pulling casually on the strings of a large, weathered acoustic guitar. “It’s a warhorse”, I say. He smiles and tells me that this is the guitar he is pictured playing on the back cover of Alive on Arrival, his 1978 debut, a fact that delights me more than I risk letting on. The way his left hand jumps about the fretboard reminds me of improvisational guitarists like Derek Bailey and John Russell, but the sound produced speaks of years spent studying and writing carefully crafted melodies infused with folk, country, and pop.

I ask whether nearly 40 years after the release of his first album he still finds new aspects of old songs to keep him interested. “Absolutely”, he says in a soft Mississippi accent, “Even a song like ‘You Cannot Win If You Do Not Play’ [Alive’s closing track], which I’ve probably played 3,000 times. I’m still finding new ways to play the guitar on it, especially when I play solo. It’s a three chord song but it’s still interesting to me, the ways that it gets a little more sophisticated through the years.”

Many of those early songs are lively ensembles—‘Cellophane City’ is a masterclass in how to build a song evenly over five minutes, opening with a quiet, pseudo-reggae beat and crescendoing with a ringing saxophone solo—but Forbert now tours with only his voice box and a guitar. I ask whether it’s easy to reproduce the energy of those tracks in a solo performance.

“No, it’s real hard. But if the audience is really going with it then it’s okay. The other night someone kept on requesting ‘When You Walk In The Room’, and I hadn’t worked out how to do the melody, but then these guys on the front row sang that. If the spirit is there in the room you can go with something like that. With the audiences, each night is a different animal. And when they’re really involved in a good way you can do anything you want pretty much, and that’s what I love most of all about this thing, because I like it to be pretty spontaneous.

“Even playing with a band live clips my wings some. I won’t stick to a setlist, and they know it, but you can’t play something that the band doesn’t know. But I often play songs that I don’t know [while playing solo] if the spirit is right, because I know that if I make a mistake the audience is going to be okay, and that’s really fun. It’s a little like jazz, that you’re just taking those chances.

“I would hate to be in a show that’s so big. I could never do a broadway play. But even a bigger arena show, the bigger they get, the more constructed they have to be, the less room there is for risk-taking.”

I’ve spent much of the last few weeks thinking about why I was so taken by Forbert’s music as a teenager. Certainly one mark of a good songwriter is the ability to write about love with sincerity, simply because there are too many love songs around for most to have lyrics worth listening to. John Martyn and Joni Mitchell, for example, both wrote about love using language that would never have been used had they never picked up a pen. Forbert has written some enviably beautiful romantic lyrics–You’re too much for me/ I’m a worn out sail/ On a sidewalk sea–and a devastating song, ‘Sadly Sorta Like a Soap Opera’, addressed lovingly to a victim of domestic violence.

He can write politically as well. His epic The Oil Song chronicles the world’s mass oil spills, and he will often pen and perform additional verses in response to the most recent disaster. He wrote The Baghdad Dream questioning the wisdom of the Iraq War, and in the wake of the 2008 financial crash told unrepentant financiers: You’ve set the world ablaze/ Now give yourself a raise.

“It’s when something really fires me up,” he says when I ask what motivates his forays into politics, “It’s when something gnaws at me until I think I might have something to say, or at least some way to put into a song what’s gnawing at me. It’s just sometimes there are things that you find you want to write a song about”.

But he is at his most potent when thinking aloud about the everyday, and does so with clarity and humour: ‘You gotta have insurance, boy, to drive your car to work/ And wind up down in court with some bad actor neck brace jerk’, or ‘It’s often said that life is strange/ Oh yes, but compared to what?’

It strikes me that, perhaps as a direct result, someone reading a set of Forbert’s lyrics would often be able to guess the age of the person writing them. Try it with ‘All we do is talk about the dreams we share/ Talkin while they vanish in the thin hot air/ Hey listen, mountains move/ Ain’t there a time frame here?’ or ‘The male of this here species lives for eighty years or so/ Starts to see the mess he’s made and then it’s time to go’.

I ask whether over his long career he has consciously documented the passage of time. “You just work with inspiration,” he says, “If you get some inspiration you want to go with it. You make observations. It’s not an overall theme to chronicle the ageing process but it is happening to me.”

There isn’t much sign of it later that evening. He plays an energetic setlist, and moves onstage with the same youthful malleability as in any of the live footage from his four decades performing. At the close of the interview I had asked how long he plans to keep touring. “As long as I can,” he replied, “I’m not looking forward to sitting down and playing. I’ll cross that bridge when I come to it, but I don’t care to sit down.”

Filed under: Music

Comments