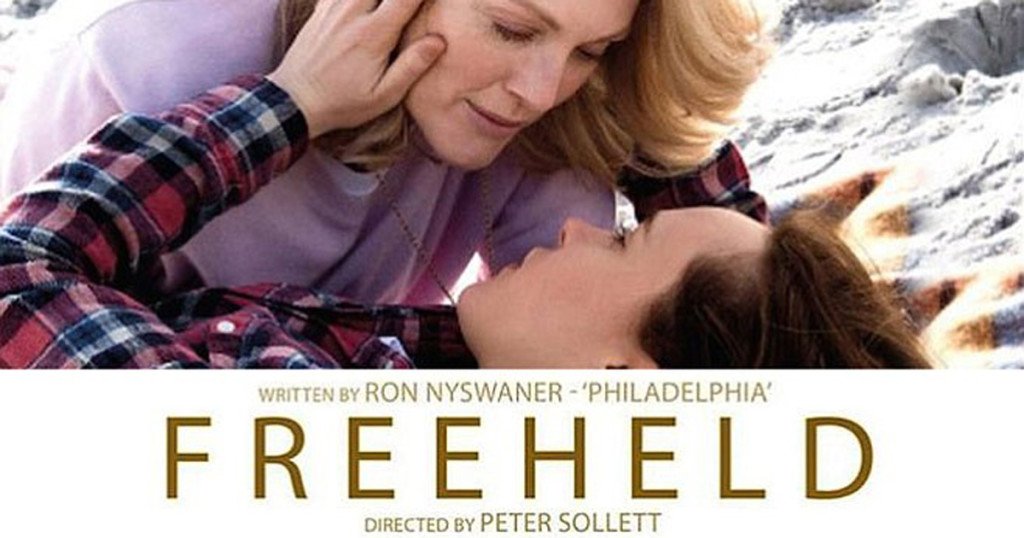

Review: Director Peter Sollett’s Freeheld

February 23, 2016

With the issue of marriage equality occupying front and centre of the US national debate, Freeheld seemed perfectly poised to cut a swath through awards season. Then Carol (2015) was released, and Freeheld receded into the overpopulated morass of also-rans. Taking its cue from Cynthia Wade’s 2007 Oscar-winning short documentary, Peter Sollett’s dramatic adaptation went through development hell for almost six years – a portent of the problems inherent in the finished product. Freeheld tells the story of Laurie Hester (Julianne Moore), a New Jersey police detective who is diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Hester fights the county’s freeholder committee for her pension to be passed on to her partner, Stacie Andree (Ellen Page). Given its emotive true-life subject matter and first-rate cast, Freeheld had the makings of a timely and important piece. But so much about Freeheld feels mishandled.

Freeheld is written by Ron Nyswaner, a gay activist who previously penned the screenplay for Philadelphia (1993). Everything Nyswaner got right in Philadelphia he botches here; the activist in Nyswaner does battle with the dramatist, and the activist wins out. Nyswaner fleshes out the scenes captured in the documentary with a rather plodding procedural subplot and a soft-centred romance; the overall effect is a clumsy jumble of tearjerker and civics lesson which has a distinctly ‘TV Movie of the Week’ tinge. Beyond the leads, characterisation is paper-thin, with Central Casting antagonists and activists who utter cringeworthy dialogue. Freeheld piles contrivance upon contrivance, and tries to juggle so many dramatic balls that the whole thing is rendered dramatically inert. It is perfectly laudable for a film to have a thesis, but not at the expense of its narrative integrity.

Sollett, whose previous major credit is the winsome Rom-Com Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist (2008), is a problematic choice to helm the film; his workmanlike direction does little to remedy the screenplay’s shortcomings. The actual scenes of the freeholder meetings shown in the documentary are much more stirring than the mannered speechifying on show here; there is much to be said for direction which does not draw attention to itself, but the freeholder meetings on which the film’s dénouement hinges fail to match the tension and passion of the real thing – a brilliant example of how to shoot these kind of scenes with dynamism can be seen in David Simon’s excellent HBO mini-series Show Me a Hero (2015).

Moore is a truly fearless actor, and never anything less than compelling as Hester, a role which has parallels with her Oscar-winning turn in Still Alice (2014) in its depiction of an accomplished woman losing control in the face of illness. Page was with the project for the entire duration of its tortuous passage to the screen; this has clearly been a labour of love for her and the early scenes of Laurie and Stacie’s burgeoning romance are shot through with genuine tenderness. For everything else that is wrong with Freeheld, there is a solid relationship at its centre. It’s strange to see Michael Shannon in a ‘straight’ role as Laurie’s police partner; one has become so accustomed to seeing Shannon playing psychos and weirdoes that the effect is somewhat jarring, but he uses gait and gesture to carve out something resembling a character. Steve Carell plays brash activist Steven Goldstein with quasi-comedic élan; it is a role that at one time would have been tailor made for Harvey Fierstein, and it is occasionally amusing to see him interact with the laconic Shannon.

While it is great to see female stories being told, and gay characters whose domestic life is shown with prosaic matter-of-factness, Freeheld is the dictionary definition of worthy, amounting to little more than a Lifetime movie wrapped in indie clothing. One can trot out the usual qualifiers in defence of Freeheld – its heart is in the right place, it is a story which needed to be told – but the film wears its importance as a free pass to abjure the rules of successful socially conscious filmmaking laid out by the likes of Capra and Kazan. Its intentions may be noble, but Freeheld never really reconciles its sense of mission with a coherent structure within which to make its progressive points.

Find Daniel Palmer on twitter at @mrdmpalmer.

Filed under: Film, TV & Tech

Tagged with: ellen page, film, freeheld, julianne moore, Peter Sollett, Ron Nyswaner

Comments