Review: Monday @ Sheffield’s DocFest

June 23, 2016

White Rage

Unlocking the Cage is the latest from husband and wife team D.A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus, and follows lawyer turned animal activist Steven Wise as his Non-Human Rights Project seeks to break down and the ‘artificial wall’ which separates human and non-human life. Wise and his team venture into ‘terra nova’ as they fight for the legal personhood of apes, elephants and cetaceans; and search for a primate whose confinement represents a denial of its ‘autonomy and self-determination’. Unlocking the Cage throws up a number of ethical questions, and strays into difficult territory at times, but above all it is a trademark Pennebaker/Hegedus character study. Pennebaker and Hegedus seem more interested in Wise as a subject than the cause for which he fights; their methods preclude the possibility of a more thorough examination, and what remains is a meandering profile of an affable if quixotic figure which fails to clarify or dramatise the issues in any meaningful way. This may well be the beginning of a social dialogue, and posterity may look more kindly upon it, but as it stands Unlocking the Cage is a minor work in the Pennebaker/Hegedus canon.

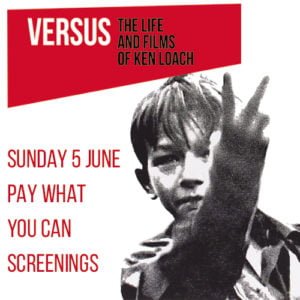

Versus: The Life and Films of Ken Loach is Louise Osmond’s affectionate look at the fifty-year career of Ken loach, produced in collaboration with Loach’s own Sixteen Films. As one would expect from a film made with its subject’s full co-operation, Osmond’s film never strays far from its admiration of Loach, often to its detriment. Versus was intended to mark Loach’s retirement from filmmaking, but the Cameron government spurred Loach back into action, and we see him at work on I, Daniel Blake as friends, family and collaborators line up to touch the hem of his garment. The most interesting sections of Versus deal with Loach’s political awakening; his early days in TV, in which the dramatic battering ram was forged with ground-breaking, incendiary work like Up the Junction (1965) and Cathy Come Home (1966); and his decade in the wilderness after a disastrous foray into documentary. But where Versus falls down as a fully-formed portrait is its unwillingness to engage Loach’s detractors: it would have been nice to hear from at least one of the voices who reviled Hidden Agenda (1990) or The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006) for being ‘pro-IRA’. It does a disservice to such a combative and divisive figure as Loach to exclude the opposite side of the debate. The sole concession to ambiguity is the admittance that Loach made ads for Nestlé and McDonalds when the work dried up in the ’80s. Loach himself comes across as a quite firebrand, possessed of an inner-steel his unassuming demeanour belies; there is little in the way of personal revelation, which speaks to his unswerving focus on the purity of the work. Seeing the clips from Loach’s major works which pepper Versus, one is struck by their fearlessness; which only serves to make its absence in the rest of Versus all the more glaring.

Versus: The Life and Films of Ken Loach is Louise Osmond’s affectionate look at the fifty-year career of Ken loach, produced in collaboration with Loach’s own Sixteen Films. As one would expect from a film made with its subject’s full co-operation, Osmond’s film never strays far from its admiration of Loach, often to its detriment. Versus was intended to mark Loach’s retirement from filmmaking, but the Cameron government spurred Loach back into action, and we see him at work on I, Daniel Blake as friends, family and collaborators line up to touch the hem of his garment. The most interesting sections of Versus deal with Loach’s political awakening; his early days in TV, in which the dramatic battering ram was forged with ground-breaking, incendiary work like Up the Junction (1965) and Cathy Come Home (1966); and his decade in the wilderness after a disastrous foray into documentary. But where Versus falls down as a fully-formed portrait is its unwillingness to engage Loach’s detractors: it would have been nice to hear from at least one of the voices who reviled Hidden Agenda (1990) or The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006) for being ‘pro-IRA’. It does a disservice to such a combative and divisive figure as Loach to exclude the opposite side of the debate. The sole concession to ambiguity is the admittance that Loach made ads for Nestlé and McDonalds when the work dried up in the ’80s. Loach himself comes across as a quite firebrand, possessed of an inner-steel his unassuming demeanour belies; there is little in the way of personal revelation, which speaks to his unswerving focus on the purity of the work. Seeing the clips from Loach’s major works which pepper Versus, one is struck by their fearlessness; which only serves to make its absence in the rest of Versus all the more glaring.

White Rage is an ambitious but awkward hybrid which seeks to shed light on the mindset behind mass shootings, but suffers from some structural issues and a lack of narrative coherence. In seeking to dramatise this phenomenon, veteran Finnish director Arto Halonen makes some bold stylistic choices which rarely work in the film’s favour; particularly irksome is the preponderance of drone shots, which quickly become repetitive and immediately timestamp the film. The documentary component of White Rage is often difficult to discern – there are dramatic recreations from the life of an alienated and bullied young man called Lauri, with the words of an anonymous ‘real person’ narrating Lauri’s growing desire for violent revenge on his tormentors. White Rage‘s visual excesses give it the feel of a lurid crime recreation show, with sweeping shots set to bombastic music; though Kirka Sainio’s sound design is effective in creating some unsettling ambient soundscapes. This issue was explored with greater depth in explicitly dramatic works like Elephant (2003) and We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011); indeed, much more effective than White Rage in distilling this issue was the short film which preceded it, Speaking is Difficult, which I urge you to watch.

Care is Deirdre Fishel’s timely and touching examination of the home care industry; an industry upon which an ageing population that wishes to age at home will increasingly rely. Fishel studies the relationship between care givers and recipients from various walks of life, and underlines the perils inherent to both in a ‘wild west’ for-profit system. Fishel captures the day-to-day routines of domiciliary care with intimacy and compassion, showing people at their most vulnerable being attended to with patience, devotion, diligence and kindness by carers who often go beyond their job description but exist in an occupational limbo: carers are insufficiently trained and poorly paid, working long hours without benefits or protection – labour laws do not extend recognition to home care providers. It is an indictment of the system that hard-working people such as these exist on the brink of penury; it is equally grotesque that people requiring care must plunge themselves into debt to finance their care. Care wears its activism lightly, making its point with stories about personal bonds which transcend their economic underpinnings. It is a celebration of those who do this vital but unheralded work, and a warning to the rest of us; illustrating that ‘ability is a temporary thing’, and we may be looking at our own future without greater oversight of the industry.

Follow Daniel Palmer on Twitter at @mrdmpalmer.

Comments