Exhibition review: The Body Extended: Sculpture and Prosthetics @ Henry Moore Institute, Leeds

August 7, 2016

TSOTA’s Rich Jevons talks to Lisa Le Feuvre, Head of Sculpture Studies at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds about curating her latest show.

Firstly could I ask about the genesis of the exhibition, how the exhibition came about?

We’d been thinking a lot about sculpture and the body and obviously that’s so important in figurative sculpture. And we’ve also been thinking a lot about the relationships between technology and sculpture. We did a lot of research about that thinking through various ideas. So we focused down on the period just after the First World War and something really interesting happens then. There seems to be a dichotomy between sculptors who are looking at how technology can create a better future and can save people; and also how technology can create a complete dystopia. So when we looked at this period we saw a radical change as a result of the global military conflict that was fought with analogue means. Casualties were of a nature never been seen before and these bodies had to be fixed.

Heinrich Hoerle, Monument to Unkonwn Prostheses, 1930, Courtesy of Medienzentrum, Antje Zeis-Loi / Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal

So the medical profession responded, sculptors responded. Artists like Heinrich Hoerle (1895-1936, Cologne) made a folio that is calling to help the veterans. It was about trying to get people to think about how they could help these people. Others like Jacob Epstein (1880, New York – 1959, London) made a horrific technologised body. It seemed to us that that period in history really resonates in all the sculpture that was being made.

You’ve deliberately put artworks next to actual prosthetics, did you want us to compare and contrast the two?

It’s a good question, I wouldn’t say contrast because it is more about looking at the commonalities. When you think about sculpture you think about form but you also think about what something looks like. But also what does it do? If you think of the processes of sculpture it is about skill but it is also about content as well. This applies too to the skill of the clinical prostheticist is really important.

Some of the pieces were made for aesthetic reasons too so it as not quite so disturbing to go out with facial wounds or a missing limb.

You have really just completely cracked the nut there because it is about a public life. And one of the things that was so tragic for soldiers with horrific facial injuries was the reaction of others. Children would be frightened of their fathers, one’s romantic partner would find it very difficult.

Lisa takes me on a tour of the show: ‘This work Marie Christine by Michael Kienzer (b. 1962, Steyr, Austria) consists of three really basic elements: a really old chair, a pair of artificial limbs for a child, and a long string of elastic. It is about making a game where you gradually move the elastic right up to your neck. So it makes you think of children in the many countries where there are landmines. So it’s a game but it’s also a game that involves jumping and it is looking at the horrors of war but also that things can be fixed.

‘This is not an exhibition that is looking at only sadness – it is about how culture and medical science respond to the surrounding world. If our world is difficult, if it has conflict that seeps through into every aspect of society.

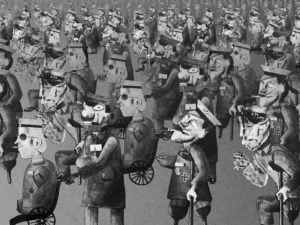

‘This picture of Epstein’s original Rock Drill which is a technologized body but then a few years later what Epsten did was he destroyed it and remade it to make Torso in Metal which gives a sense of a terrifying body. And there is this beautiful photomontage by Alice Lex-Nerlinger (Berlin, 1893-1975) she has made a composite body with the right leg being a prosthetic which she would have sourced these from catalogue for prosthetics. Wyndham Lewis’ piece from 1913 is a very technologised human , standing tall, articulating, the head has turned into some kind of receiver, and no one wants that future.

Yael Bartana, Degenerate Art Lives, 2010, Courtesy of Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam and Sommer Contemporary Art., Tel Aviv

‘This is based on Otto Dix’s work that was one of the stars of the Degenerate Art Show of the Nazis ad it may have been lost but at the very first Dada art fair there was photography from this exhibition. Yael Bartana (b. 1970, Kfar-Yehezkel, Israel) is really interested in his painting that shows the veterans returning from war needing prosthetics. So she has re-animated it.

‘This work by Martin Boyce (b. 1987, Glasgow) and one of the forms is almost the same as one of the splints on display which have now become museum pieces. Then this piece by Louise Bourgeois (1911, Paris-2010, New York) has really drawn on anecdotes of her childhood and she wanted to express her shock when working in the Louvre that the entire staff almost has prosthetics.’

If there was one thing you would like people to take away from the exhibition what would it be?

For me it is about how all of us have the desire to exceed the limits of our own body. One of the things that make us so human is our frailty, the limits of our body, and then what happens when we exceed that. I’d really like people to think about the thing we know best, our own body, how we move in the world and how our limbs have form and function and at times can be extended.

Showing until 26th October 2016 at Henry Moore Institute, Leeds.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: Henry Moore Institute, Lisa Le Feauvre, Rich Jevons, Sculpture & Prosthetics, The Body Extended

Comments