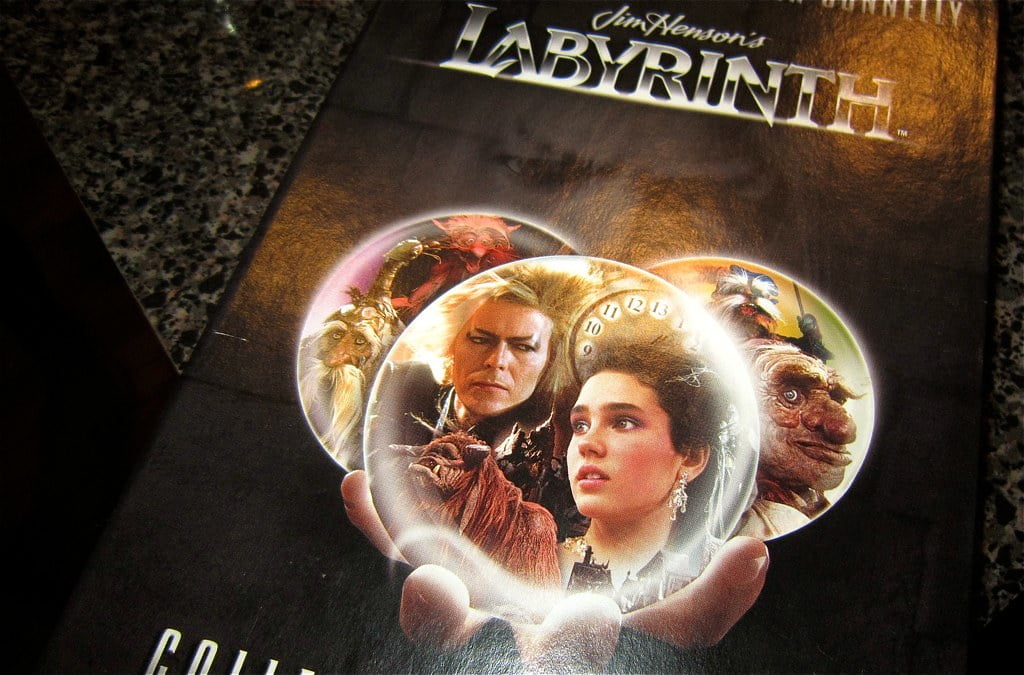

“You have no power over me. –Sarah (Labyrinth, 1986)” by anokarina is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Unlike its namesake, The Bog of Eternal Stench, which featured in the iconic 1986 Jim Henson film ‘Labyrinth’ starring the inimitable David Bowie, The Bog of Eternal Superlatives isn’t a muddy wetland that leaves any unfortunate soul who happens to fall into it irreversibly malodorant, but rather a phenomenon within the cultural sector. A phenomenon that compels cultural organisations and workers, myself included, to describe any piece of work as, to quote the catchphrase of another 1980s in demand Jim, comedian and host of the darts-based game show ‘Bullseye’ Jim Bowen, as “super, smashing, great!”

I get it; it makes good business sense, and it’s hardly likely that the marketing for any future re-issue of ‘Labyrinth’ would use the less flattering reviews on Rotten Tomatoes that describe it as suffering from “a distinct lack of charm”, “nonsensical songs” and “no pep” (for the record, all of which I vehemently disagree with). Promoting the beneficial impact of arts, culture and heritage can help attract audiences and investment and highlight the accomplishments – often achieved in spite of considerable odds – of a mostly underpaid and overstretched workforce.

It’s understandable then that The Bog of Eternal Superlatives is so enticing; it offers bucket loads of positive affirmations and provides some respite from the daily grind of a cultural sector increasingly expected to do more with less. Once fully immersed in it, you’ll become proficient in describing, evaluating and promoting any project (no matter how perfectly ordinary) in the most glowing terms possible. Before long, you’ll have a superlative-centred vocabulary the envy of any writer at Marvel Comics assigning epithets to their ever-expanding universe of superheroes: amazing, fantastic and sensational!

So what’s driving our overconsumption of superlatives? Simply put: competitiveness. Cultural organisations and workers are under immense pressure to demonstrate positive impact in order to release funding. Funding that is in unprecedented demand due to the ongoing harm caused to the economy, environment and society at large via austerity, Brexit, budget cuts, cost of living crisis, Covid and Trussonomics. Who knows, maybe the British Museum will stage an exhibition that examines the primary cause of this financial, political and societal turmoil? I can’t see any reason why the British Museum’s current chair of trustees could possibly object to such a show.

Understandably, not every cultural worker is as comfortable with competition as, say, a former Tory Chancellor of the Exchequer might be. The competitive atmosphere surrounding the process of cultural organisations applying to Arts Council England to either retain or gain National Portfolio status from 2023 onwards was even likened by some cultural workers to the dystopian plot of another acclaimed 1980s film, George Miller’s 1985 ‘Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome’, starring the irrepressible Tina Turner. In it, the inhabitants of the post-apocalyptic Bartertown are locked in an unedifying yet unavoidable struggle for survival, resources and power.

Deploying superlatives to bag the resources necessary to ensure a viable future for a cultural organisation is one thing, liberally over-applying them in pursuit of prestige is quite another. Take the pending relocation of the English National Opera to outside of London, for instance. When the shortlist of potential new locations was announced, some movers and shakers in these places launched themselves headlong into The Bog to big-up their arts, culture and heritage on offer in order to bolster their nomination. This caused one almighty superlative splash and subsequent surge, sweeping away any apparent consideration for those cultural organisations and workers already in or near these areas facing uncertain futures, if any future at all, and sinking any discernible empathy for concerned staff at the English National Opera.

Persistently plunging into the bog for purely reputational reasons, and things can turn positively toxic. Before long, you can begin to lose all sense of perspective, gloss over exploitative practice and get besotted with perfectionism. It can feel like you’re trapped in a never-ending impeccably choreographed exclusive opening in the grand entrance hall of a venerated cultural institution – but you’re on duty. Not only are you forbidden from taking advantage of the complementary booze, but you’re under strict instructions to smile effusively and convince invited VIPs the likes of David Bowie, Tina Turner and Jim Bowen, without appearing feigned, that the project has been an astonishing, incredible and spectacular success, and nothing but. It’s exhausting.

In my humble opinion, I’d also include actor, director and Marvel Cinematic Universe alumnus Taika Waititi on any opening guest list, especially if he was going to dispense the kind of sage advice that he shared during his musings on creativity for Adobe MAX in 2020: “Here’s the thing: 90 percent of all ideas are shit, 90 percent of all art is terrible, 90 percent of all movies are pretty bad. And I think if you kind of take that ratio into account, it allows you to relax a lot more. You don’t have to worry about making something good all the time.” Alongside the Waititi Ratio, as I like to call it, there are also other ways to prevent yourself from becoming submerged in The Bog and take advantage of a toxic positivity purge, with projects like FailSpace and Fuckup Nights both providing safe and supportive ways to share and learn from stories of failure.

I’m not calling for a cultural sector devoid of superlatives; I’m not that pessimistic. That being said, there’s a definite need for more resources devoted to superlative-free safe spaces in which cultural organisations, workers and their collaborators can take the opportunity to deservedly decompress and open up about the less successful or less salubrious aspects of their work or the sector.

Expanding opportunities for genuine reflection would help cultural organisations and workers to flag issues without experiencing the kind of self-doubt that writer Gabriela Wiener endured shortly after imbibing the psychoactive brew ayahuasca, as recounted in her 2018 book Sexographies: “I chastise myself for my relentless skepticism, my pedantic sarcasm, my unfettered cynicism.” The good news is, however, that Gabriela, after “mercilessly berating” herself in this way, forgave herself and began to “laugh out loud, joyfully.” I think we could all benefit from taking a leaf out of Gabriela’s book by embracing our inner critical thinker or, in my most convincing impersonation of David Bowie as Jareth the Goblin King in ‘Labyrinth’, risk getting stuck in The Bog of Eternal Superlatives forever!

Disclaimer: No ayahuasca or any other hallucinogens, for that matter, were consumed in the writing of this piece.

Comments