Film review: Ben Wheatley’s High-Rise

March 23, 2016

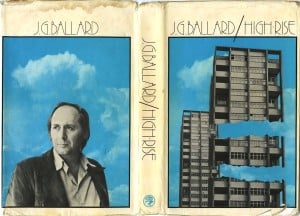

If any writer could be said to have sketched the contours of early-twentieth-century malaise, it is J.G. Ballard. We live in increasingly Ballardian times: we have been conditioned to embrace the barbarity of infinite choice; we are atomised and adrift; we subscribe to an anatomical view of life in which sex, death and technology coalesce in garish loops. Ballard described himself as ‘a one-man safari, pushing through the jungle’, and saw the future as ‘a vast, endless suburb, ordered but interrupted by acts of totally unpredictable violence’. Nowhere is this worldview best articulated than in his 1975 novel High-Rise, in which the inhabitants of an upscale tower block ‘surrender to a logic more powerful than reason’. In High-Rise, Ballard foresaw the social shift which would come to fruition with the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, and extrapolated with startling and surrealistic results.

High-Rise centres on Robert Laing (Tom Hiddleston), a young doctor who has moved into the twenty-fifth floor of the high-rise. Laing is struggling to get over the recent death of his sister, and soon becomes involved with Charlotte Melville (Sienna Miller), a single mother who lives a floor above him with her precocious son, Toby (Louis Suc). Laing finds himself becoming the squash partner of the building’s architect, Anthony Royal (Jeremy Irons), who is recovering from a car crash and resides in a luxurious penthouse on the top floor. Laing meets Richard Wilder (Luke Evans), an opportunistic documentary filmmaker who is stuck on the second floor and wants to make a film about the inequalities that exist within the high-rise. Laing finds himself in the middle of a full-scale inter-floor tribal conflict as the high-rise begins to malfunction and descends into a morass of degradation and disorder.

To tackle Ballard is an audacious act; David Cronenberg set the bar very high with his unflinching adaptation of Ballard’s polymorphically perverse 1977 novel Crash (1996). But Ben Wheatley’s previous work – the stunning Kill List (2011) and the riotous Sightseers (2012) – suggests he is up to the task. The end result of Wheatley’s fourth collaboration with writer Amy Jump is a major step forward for both, fulfilling the promise they showed in their previous low-budget offerings. High-Rise harks back to the work of British New Wave master Lindsay Anderson in its surrealistic, darkly comic tone; particularly Anderson’s overlooked classic Britannia Hospital (1982) in its sense of the setting serving an allegorical function. High-Rise is retro without being nostalgic; it essays the present by evoking the past, a time when post-war austerity gave way to a consumer idyll; but one laced with inflation, oil shocks, simmering class antagonism and the spectre of authoritarianism.

High-Rise by J G Ballard

Much like Ballard’s one-man safari, Wheatley cultivates a probing but dispassionate eye, positioning himself as an observer to the chaos, interspersed with vertiginous shots of the high-rise, which chokes the horizon like a spacecraft designed by Le Corbusier. Jump’s screenplay has a commendable lack of reverence for the source material, condensing many of Ballard’s conceptual preoccupations into scenes that play out as satirical pantomime. Mark Tildesley’s production design captures the ominous opulence and rampant squalor the building’s arc encompasses – referencing Alex Cox’s Repo Man (1984) in the supermarket sequences – while Laurie Rose’s cinematography recreates the gaudy-yet-sterile hues of the era. Clint Mansell’s score is as integral to the film’s effectiveness as Wendy Carlos’s work on A Clockwork Orange (1971), heightening the pervading sense of unease.

The casting of Hiddleston in the central role is a canny move; Hiddleston is an inherently likeable presence and, much like Hitchock’s use of Jimmy Stewart, the disjuncture between what the actor embodies and the role represents strikes a disquieting note. Laing is a man hiding in plain sight who chooses to row against the tide, and Hiddleston skilfully offers glimpses of the maelstrom swirling just below Laing’s urbane surface. High-Rise has an embarrassment of acting talent on show; indeed, one of the film’s shortcomings is the sheer number of characters it struggles to introduce. Irons is in fine form as Royal, a weary deity who conceived the high-rise as ‘a crucible for change’ and sees his creation turn into ‘a huge children’s party that got out of hand’; Keeley Hawes is in full Marie Antoinette mode as the aristocratic Ann Royal; James Purefoy delivers a wonderfully dissolute performance as the snooty gynaecologist Pangbourne; Evans brings a sense of threat to the truculent Wilder; Elizabeth Moss is a study in quiet desperation as Wilder’s dissatisfied wife, Helen; and Dan Renton Skinner stands out as Royal’s foul-mouthed goon, Simmons.

While it never quite hits the subversive heights of Crash, High-Rise honours the novel’s thesis while casting the story forward to incorporate a pointed critique of the aspiration cult which for the past three decades has driven its acolytes to regard themselves as stakeholders rather than citizens. Ballard’s social prescription for small doses of psychopathic violence is sugared with pitch-black humour and a stylistic daring which occasionally succumbs to the madness it portrays, driving the narrative into sybaritic cul-de-sacs. High-Rise marks Wheatley’s ascension into the ranks of great British mavericks like Nicolas Roeg; it is a flawed but undeniably vital piece of work that is destined for cult status.

Follow Daniel Palmer on Twitter at @mrdmpalmer.

Comments