I joined the DIY publishing collective Snitch late in the summer of 2018 to edit, print and distribute publications. Snitch was set up by Rory and Jack, two disenfranchised art school graduates, to address the absence of freely available opportunities for artists, particularly unestablished ones.

I joined the DIY publishing collective Snitch late in the summer of 2018 to edit, print and distribute publications. Snitch was set up by Rory and Jack, two disenfranchised art school graduates, to address the absence of freely available opportunities for artists, particularly unestablished ones.

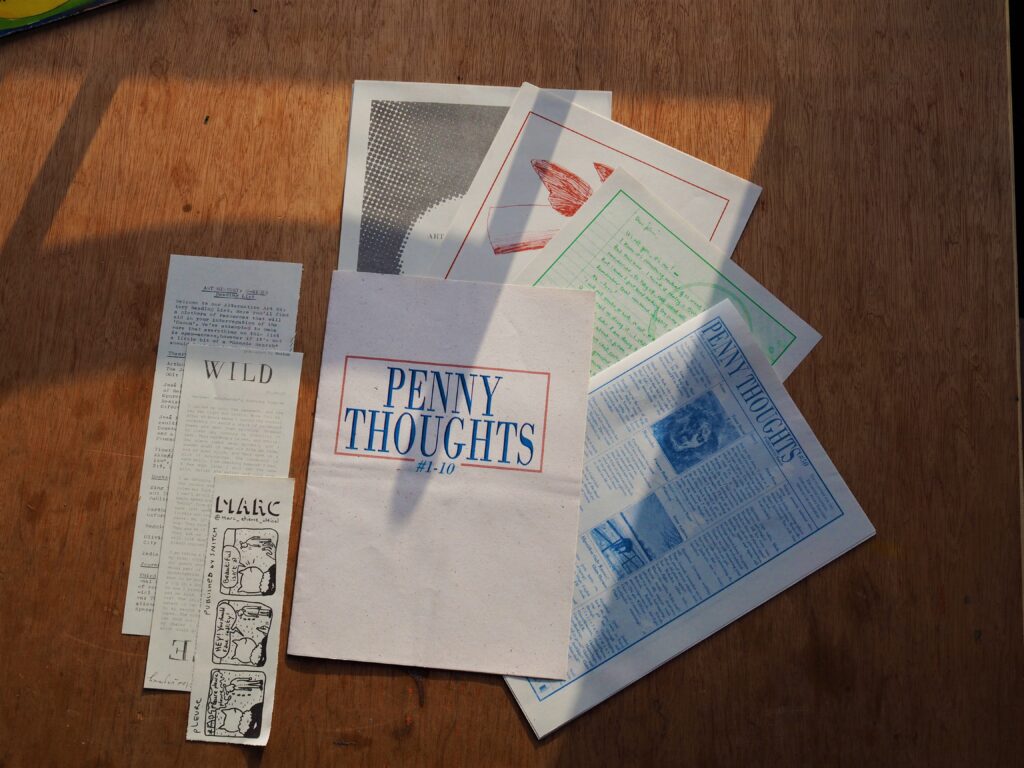

Their frustration was distilled into Penny Thoughts, a free, single-sheet, double-sided broadside collecting submissions ranging from finished works to ephemera. Contributors to Penny Thoughts have sent in all sorts, and among my favourites are a notes page poem written in auto-correct, a love letter to planet earth, and an RPG (role-player game).

Pretty soon however, my role in the collective changed. I assisted with dreaming up new publications, a podcast, events and club nights. At the time, all of these iterations seemed completely natural. The trajectory was obvious; we would do more, make more. There was a checklist: website, Spotify, Soundcloud, Twitter, Curatorspace. It was easy to imagine us as publishing monoliths.

Despite our growing online presence, we remained a somewhat nebulous set-up. We never quite became ‘professionals’ in the sense of registering Snitch as a CIC, or a charity – or anything that might make us bureaucratically legitimate. We were professionals insofar as we loved to graft. Rory loved the all-nighters. I loved the feeling of suffocating in my own post-its. For that reason, the first year of publishing was as exciting as it was precarious. There wasn’t any money, and both Rory and Jack would subsidise print runs with their own earnings. For a time, we took to paper theft, orchestrating elaborate heists into The University of Manchester’s various libraries, heaving reams of paper into back-packs.

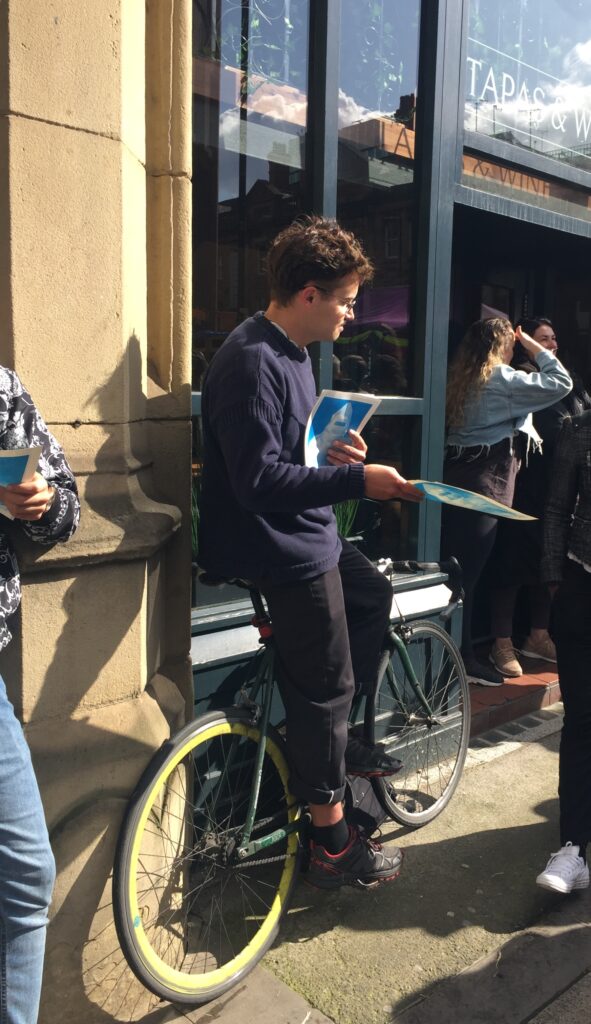

We were getting good feedback too. To the extent that there was something glamorous about a minor incident of copyright infringement. I also enjoyed moments when I’d hand someone a copy, and feigning interest they’d crumple it into a back pocket, adding “I’ll read this later.” All of this chimes with what Nicholas Thoburn, author of ‘Anti-Book: On the art and politics of radical publishing’ comes up with when describing ephemerality in relation to small-press publishing. He calls it “existence courted by destruction”.

At the start of 2020, just as we began treading more heavily in Manchester’s art world, there was the inevitable stand-still. And while we all know how it went, the problem that arose for us, as physical print publishers, was that touch was not only rare but threatening. So, we cancelled events, we withheld the week’s worth of issues and waited. Almost immediately, the world moved aggressively online. Instagram was alight with open calls, digital exhibitions, online projects and collaborations, podcasts, Zoom talks and conferences. Grayson Perry’s ‘Art Club’ was on telly and acrylic paint was sold out online.

Everything amounted to the endless scrolling. Everything we were doing was reflected back at us, by creatives with far better phone cameras and marketing strategies. We felt rejected, unseen. And while I don’t mean to betray my tribe with this slough of despond, there was something too earnest and too extreme happening behind the explosion of online creativity. We felt a crisis looming. Rory and I were both unemployed and despite our efforts to overhaul all publishing activities online, we felt lost and overwhelmed everytime we sat down together to plan an issue. It was a tricky bind; on the one hand, platforms like Instagram enabled so much of our work to get seen, but on the other hand we rarely felt like we were making an impact. It gets trickier when you consider how vital the internet is as a platform for creatives who cannot access the physical spaces where art can happen. It is a great enabler and my belief in that fact cannot be overstated enough.

The problem was far more complex, partially embedded in our frantic relationship to work, as well as the sheer breadth of the internet. When Rory initially proposed ending Snitch, the product of two years’ hard work, we thought of it as giving-up. I couldn’t extract my self-esteem from Snitch; it was meant to be my thing. We hobbled along stubbornly for a while, cold and uninspired.

The ideology behind this resistance is perhaps familiar to creatives who suffer from imposter syndrome. It’s a do-or-die, adapt-or-fuck-off kind of energy. This way of thinking skewed my perspective on what was realistic, achievable and perhaps was the whole point of Snitch in the first place. Evidently, Snitch publications lived healthier, happier lives out in the open. Their existence on the internet was only ever meant to be supplementary.

Though we tried, we never quite worked out how to keep momentum on our online platform, even with the help of our three incredible friends and colleagues: Will, Dylan and Victoria. Despite the frustration and low-moods, each of them reminded us that publishing and being published makes you feel all kinds of wonder. They also reminded us that projects can be picked up again, transformed with time into something better, more refined.

Thoburn qualifies the idea that ephemeral things are “courted by destruction” by stating that it is precisely this quality that makes them enduring. Bus tickets for example, become redundant after use, but you might keep them in your wallet for a while remembering the trip you went on, who you were with, how you felt. In a similar way, it is a complex web of physical touch (scrunching up, pinning up, keeping safe, screenshotting and forgetting) that surrounds our publications.

But what I have since learnt, is that sometimes pandemic or not, projects end. Success is rarely gauged accurately, or else it is overrated. Your projects can be left abandoned, and that is really quite ok.

When in doubt, refer to the immutable words of our patron saint of trip hop, Nelly Furtado:

“All good things come to an end.”

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: covid, instagram, online, Out of print, pandemic, paper, physical, print, printed, publishing

Comments