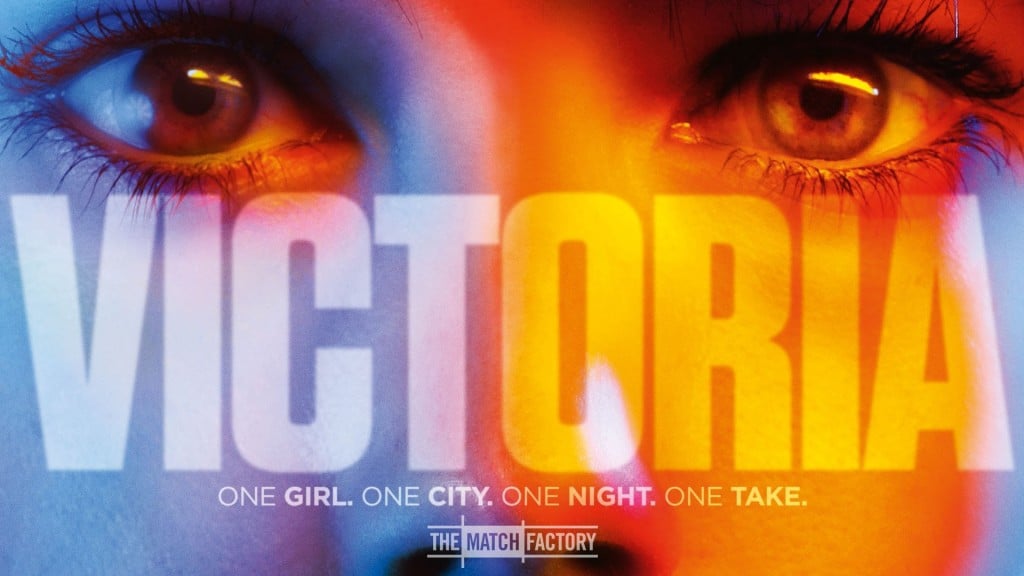

Review: Victoria by Sebastian Schipper

April 3, 2016

To reject the primacy of the cut in the process of filmmaking was for the longest time regarded as a transgressive act, the preserve of the avant-garde; the conventions of editing have been so firmly ingrained into viewers by the Hollywood system that we all fall into its rhythms, so fundamental to the grammar of cinema that their absence is jarring. Like the point-of-view perspective, the ‘single-take’ form was always regarded as a stylistic gimmick which impeded narrative clarity. The Oscars garlanded upon Birdman (2014) signalled the form’s full emergence into mainstream respectability.

Historically, the ‘single-take’ form has always been an illusion: from Rope (1948) to Silent House (2011), transitions are hidden and made to appear seamless. Mike Figgis’s daring real-time, split-screen satire Timecode (2000) and Aleksandr Sokurov’s sumptuous single-take historical sojourn The Russian Ark (2002) harnessed the nascent digital technology to push the boundaries further, but both lie more within the realm of experimental cinema. So Sebastian Schipper’s claim that he has finally cracked the formula and made a truly ‘single-take’ film that is also a plot-drive thriller is a bold one.

The 138-minute continuous take that is Victoria was met with equal acclimation and scepticism at its Berlinale premiere – Darren Aronofsky swore he saw three cuts in there. Whatever the truth, Victoria picked up a Silver Bear and swept the board at the German Film Awards. Its eponymous protagonist (Laia Costa) is a Spanish twentysomething living in Berlin temporarily, where she works for a pittance in a cafe and knows nobody. As she is leaving a club at 4 A.M., Victoria encounters a group of young men being denied access. The young men befriend Victoria and offer to show her the ‘real’ Berlin. They drink together, and Victoria begins to flirt with Sonne (Frederick Lau), the most charming and articulate of the group. Victoria tells her new friends she must leave to open the cafe, but invites Sonne to join her. At the cafe, Victoria and Sonne become more intimate. Then Sonne receives a phone call, and Victoria is thrust into a dark, violent side of the city.

The critical hosannas Victoria has received all centre on its technical accomplishments. There is no disputing the fact that Schipper and cinematographer/camera operator Sturla Brandth Grøvlen have pulled off an audacious and outstanding feat. But is it anything more than that? Victoria blends the social-realist immediacy of the Dardenne Brothers, the classic crime drama tropes of Jules Dassin, the high-concept gloss of Michael Mann and the freewheeling spirit of Jean-Luc Godard. Like the repetitive techno music that figures throughout, Grøvlen’s breathless, kinetic camerawork has a hypnotic effect, and we are swept along on what Schipper calls a ‘river of story’. It rejects the precision of an Emmanuel Lubezki in favour of a wilfully messy guerrilla approach which feels like being in a car whose driver is asleep at the wheel as it hurtles towards a brick wall: thrilling but terrifying.

But the conceit is ever-present. One can never fully escape the bravura at work; it draws attention to itself with every lurch and spin of Grøvlen’s propulsive camera. Schipper has admitted that he wouldn’t have made the film without the one-take concept, which suggests that story is subordinate to its execution – the script was a 12-page outline from which the cast developed their characters through improvisation. Taken on its own terms, the story is a somewhat formulaic heist thriller; with dim-witted thugs out of their depth, and a sinister hood (André Hennicke) doing a passable Christoph Waltz impersonation. The only area in which Victoria moves beyond these narrative conventions is in its inversion of the traditional female role within the crime canon: Victoria is not the femme fatale, but the alienated outsider who takes a wrong turn and finds her world thrown into chaos.

Victoria is imbued with the grit and energy of improvisation, there is a purity to the two central performance that come from Schipper’s empowering the cast to follow their instincts – this is the third take they shot. Costa delivers an extraordinary performance as a reckless, nihilistic spirit who steers ever-closer to the precipice. There is a definite Belmondo/Seberg dynamic between her and Lau, who lends Sonne a roguish charm underscored with doomed vulnerability. But not everyone flourishes in this permissive environment: the other characters are identikit, and serve to underline the perils of empowering actors.

Whether anything actually lies behind the initial rush of adrenaline one feels upon seeing Victoria, whether it stands up beyond the confines of the theatre experience, will be discovered in subsequent viewings. What is immediately evident is that Victoria has tremendous vibrancy, but it is a work in which we see the process unfolding before us, in which we are made aware of its mechanics, putting the viewer in the position of admirer. It may well be a film to be experienced once, with no claim to it beyond the visceral. It may not amount to much, but as an exercise in sheer sensation it is an unqualified success.

Comments