Jan Hopkins is a Sheffield based artist and writer working in drawing, making and digital media. Within her current body of work, she makes drawings in partnership with a machine. The part she plays within this collaboration is to provide the coding for the initial idea whilst the machine uses this to work from though not quite in the way you might think. The machine contributes far more to the drawing than simply printing; there are elements and variations to the final piece that come from the machine itself.

During lockdown Jan made a book of drawings that were to be her last for a while. She’s paused drawing by hand for the time being as she explores ways to communicate with machines as creative collaborators. Her research explores how an art practice working in partnership with machines can rethink our relationship with technology.

Jan Hopkins in her studio in Sheffield.

Court: Jan I should have known your studio would be like this! I absolutely love how monochromatic, ordered and calm it is. Our outfits even go with the space! Speaking of outfits, can you talk me through the knitted vest top?

Jan: Now, that was a labour of love. It’s a version of the tank top worn by Paul McCartney in the movie, ‘The Magical Mystery Tour’ that first broadcast on Christmas Eve 1967. It was filmed in colour but broadcast in black and white and that’s how I first saw it. I knitted it from black and white photos, from observation. So it’s not a replica, it’s a response. It was a struggle. I knitted and pulled it back over and over again and many tears were shed. In the end it took me a year, on and off, to finish it. The original was knitted by Freda Parkinson, Michael Parkinson’s mum, who, like me, came from Barnsley. I love how all these things join up. It was the pattern that grabbed me.

It looks repetitive but if you look carefully, there are all kinds of variations in it, all Freda. I’m a big fan of repetition in my work and pattern dominates.

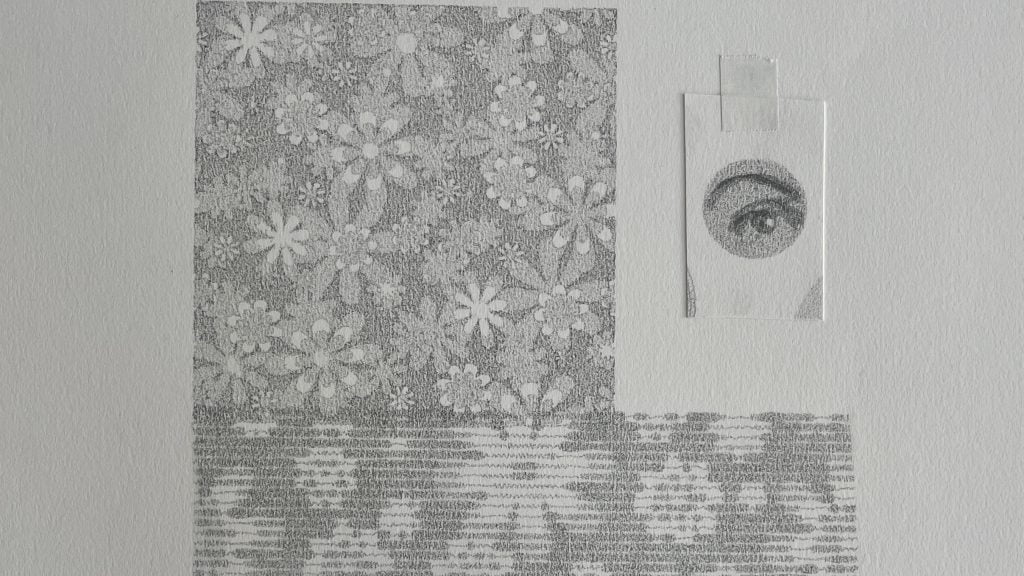

A drawing with references from the Beatles (with Paul McCartney’s eye) and Flower Power.

Court: Can you talk a little more about your relationships to tech?

Jan: I say I’m in a creative partnership with the machine. By machine, I mean the electronic computer in the first instance and in a broader context its related systems and products such as computer networks, the internet, sociotechnical systems, digital devices and software. As well as all the technology that’s travelled with me though life. It could be anything from the 1960s Bush transistor radio my parents bought just before I was born, to the global network of servers this website relies on.

As you know, partnerships or “commingle” as I call it are notoriously complicated. Just look at Lennon & McCartney, one of the greatest creative partnerships of all time, riddled with conflict, jostling for power, for control, yet at the heart of it, a deep and enduring love and respect.

I mean I’m not comparing my partnership with Lennon and McCartney but you could call it a love affair and we all know how messy those can get. Really, I think it’s about having another mind in the mix. Keeps things lively.

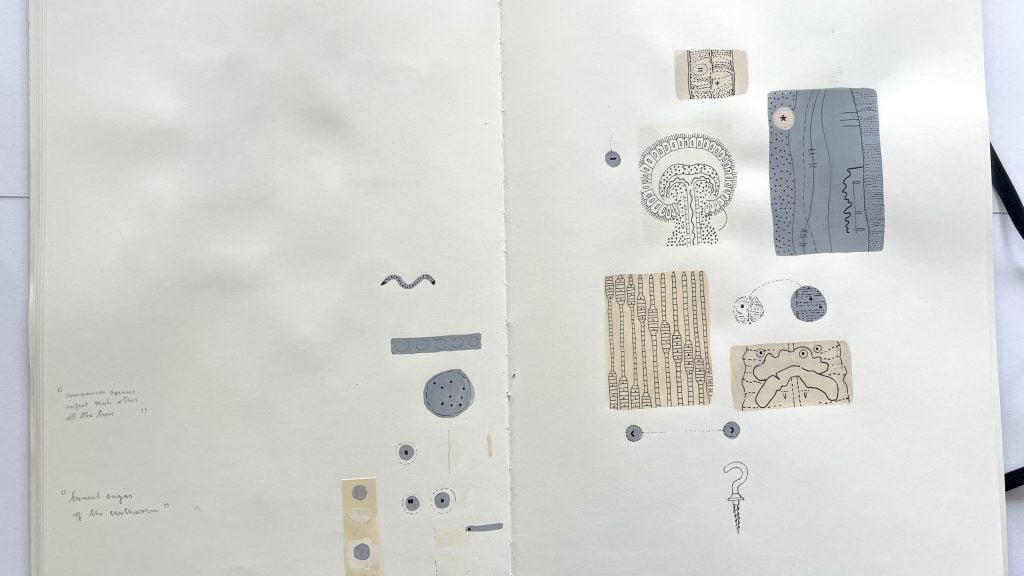

A page from the sketchbook containing the last drawings Jan made by hand.

Court: You’ve mentioned before that you no longer draw by hand. How did that come about? And do you think you’ll go back to it at some point?

Jan: I was struggling to break out of my own predictability, all the tried and tested patterns of thinking and working, even down to unconscious patterns of thinking and muscle memory. It was too cosy and I needed to get out of myself. I needed shaking up to do something different. Drawing is the thing I love to do the most and I wondered what would happen if I just stopped doing it. Of course there’d be loss, but what would I gain?

I’ve had to wrestle with a whole host of new ways of working. I have a lifetime of experience in generating images by hand and eye. Now I have to work harder at learning the language of my partner and prioritising their methodology, their expertise and machine muscle. I developed my programming skills to communicate better with my partner machine and generate ideas and imagery that best enables the hand that holds the pencil. Obviously I’m still driving this at the most basic level and I’m present in the work – that’s part of the deal – I won’t disappear – but I’m always aiming for the respect and balance that any partnership requires. Subject to subject.

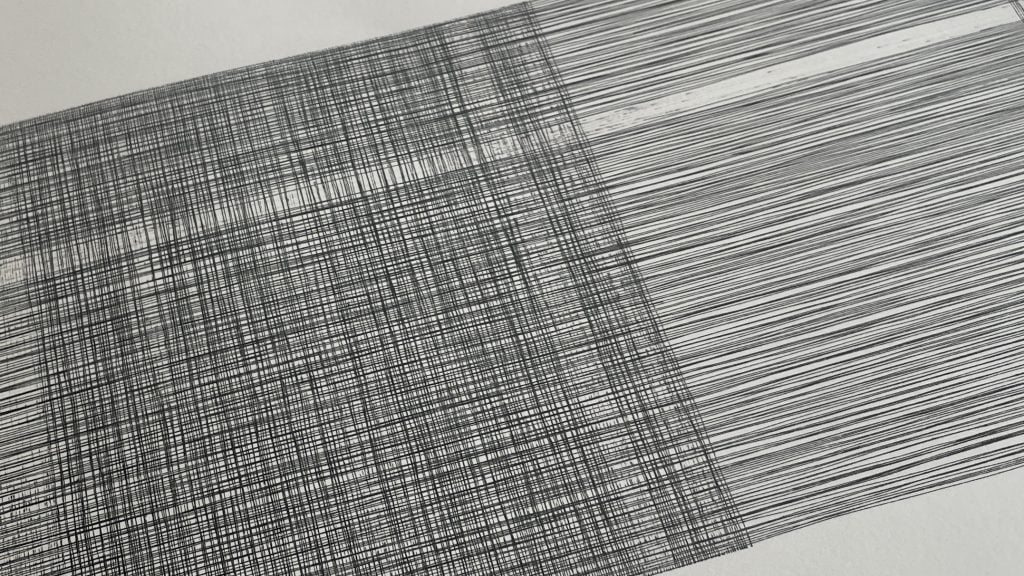

The machine drawing sineflowers.

Court: Would it be possible to see the machine draw?

Jan: Well, we can see. Here’s a program I wrote that draws sineflowers, in effect, randomly generated sine waves. It’s a relatively straightforward algorithm but you can see how the patterns it produces resemble flowers. It fascinates me that you can even start to categorise them into different types of flower: lilies, daisies and what have you. You could say that flowers are mathematical objects anyway, they’re part of the physical world after all. It’s accepted that mathematics describes the world but maybe mathematics is the world.

I just read a book by Max Tegmark called “Our Mathematical Universe: My Quest for the Ultimate Nature of Reality” where he argues just that. Worth a read. I’m a bit of a magpie when it comes to ideas, even ones I don’t fully understand. Where’s the fun in knowing all the answers?

The algorithm has randomness built in so every sineflower generated is unique and we can generate a whole flower-power-bed of them. We’ll give the Axidraw machine a pen and send them over to be drawn.

Court: That is incredible! It actually draws with a pen! And it takes a pretty random approach to the order it draws in! Are the results always the same?

Jan: The order it draws is down to the software’s decision on the most efficient order of drawing. You might expect it to draw from left to right or in an obvious order but it’s more sophisticated than that and the aim is to efficiently execute the drawing. I could ask it to draw in the order the image was drawn to the virtual canvas but that’d feel like a step too far, and anyway it’s always lovely to be surprised by the direction it takes alone. I love how unpredictable it is.

About if the results are always the same – every time the program runs, it creates a unique array of flowers and saves a file that can be drawn by the Axidraw. Of course I could ask it to draw the same file again and in that case it would draw the same path but because the drawing is happening in real time with the same materials I would use to draw, even then, there would be some analogue uniqueness to each drawing. I don’t do that though. Each generated drawing gets used only once. It’s a humany thing I insist on. Part of my/our methodology.

Court: So you’re never quite sure of the end result and that really adds to the anticipation. So what sort of work were you making before you started this collaborative approach with machines?

Jan: Mostly drawing and writing. I made artist’s books, handmade mostly, one offs, very materials based, very traditional. You have to remember, I’m not a digital native and I came through a pretty traditional art education. I didn’t meet my first computer until I was almost 30 though I admit I was immediately smitten when I did. It’s this that gives me what I think is a pretty unusual take on the digital in art in that it’s informed by a lifetime of traditional drawing practice, drawing by hand I mean. I’m not a digital artist, whatever you might think.

I started my dalliance with machines around 2012 when I was introduced to Arduino microcontrollers and physical computing by Leila Johnston when she was technologist in residence at Site Gallery in Sheffield. As soon as I saw the jewel-like electrical components, I knew it was for me. I became part of her Hack Circus Collective which was really a springboard for me.

Court: That’s fab! You mentioned a traditional art education. What was your journey into the arts?

Jan: I grew up in Barnsley, South Yorkshire. My dad was a coalminer and my mum worked for social services as a driver. So it wasn’t obvious that I’d become an artist but I was pretty precocious and knew what I wanted to do pretty early on. I credit television and radio with giving me an extended view of the world beyond my immediate environment. So important.

I wasn’t really able, for all kinds of reasons, to have a steady progression through school and art school and the like. But I persisted and eventually got myself a degree in Fine Art from Newcastle Poly in 1989. Following that, it was clear that I couldn’t make a living as an artist, though I tried. I couldn’t face living hand to mouth anymore so at 28 I trained to be a teacher and taught art in secondary school for many many years.

That and family took most of my creative energy and although I never completely gave up on being a professional artist, that ambition fell into the background. So many women fall foul of the same circumstances. I see a lot of older women reactivating their art career in later life, once caring responsibilities have been fulfilled. It wasn’t until 2017 that I had the opportunity to take back my ambition. I did an MA in Fine Art at Sheffield Hallam, was given a bursary for a year after that and then was lucky enough to be selected for the Freelands Artist Programme which gave me another 2 years of financial support and professional development.

Jan’s work exhibited in ‘The prism of the feminine: machines, oocytes, wires, potions’, Paris.

Court: We first met as you were finishing your two year Freelands Artist Programme. How were those two years for you? And you’ve since had shows in London and Paris! I know the group show in Paris included idols such as Agnes Martin. Can you tell us a bit about that?

Jan: It’s been a steep learning curve and quite the rollercoaster. I’ve learnt a lot about how to operate as an artist and that’s really valuable and I’m much better equipped to progress my career now. It has to be said though that I’m still unclear on exactly what shape my practice will take in the future. I turn 60 this week but I’m still only considered to be “emerging” as a professional artist. The idea makes me laugh.

The show in Paris came about through a writer and curator, Joana Neves who wrote about my practice for the Freelands Foundation publication, Un Chorus. She’s the Artistic Director for the Drawing Now Art Fair in Paris and invited me to be part of her show, The Prism of the Feminine: machines, oocytes, wires, potions, in partnership with Frac Picardie.

I’ve admired and studied the work of Agnes Martin for such a long time so it was an absolute joy to be in the same show, mentioned in the same breath. And not just Agnes but Vera Molnar too, a pioneering computer artist still working at the age of 99! She’s a huge inspiration. And there I was with my little animated video work wedged between these two giants. I thought, I can die happy now.

Court: That’s incredible! I always ask artists for their career highlight to date. But have we just discussed that already?

Jan: Oh, one of them, for sure. I mean, who’d have thought a coalminer’s daughter from Barnsley would be showing her artwork in Paris!? What a hoot!

Another highlight was having a pamphlet published last year by Intergraphia Books. I always wanted to be a writer so that was a huge ambition fulfilled.

Court: That’s incredible. The other question I always ask is if you have a dream project, something you would love to make happen?

Jan: You mean, apart from the solo show in New York? Well, I can dream. A solo show would be great though. I’d love to work closely with a curator to make something far out.

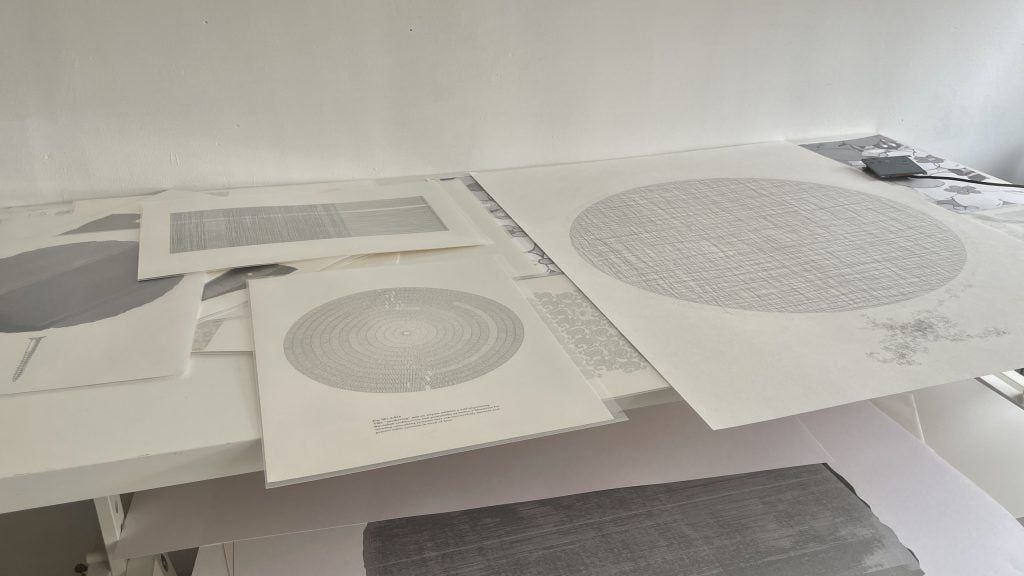

Drawings in the studio.

Court: I’m very excited to have you in the show Definitions of Drawing II that I’m curating at Sunny Bank Mills in Pudsey in August. Have you got any other shows coming up?

Jan: I’m taking part in a collective art project, the brainchild of Toni Buckby, in partnership with The Victoria and Albert Museum called An Unstitched Coif. I’m one of 40 core participants whose work will enter the collection of the V&A. Get me! The project explores an unfinished blackwork embroidery piece from the V&A collection and will feature over a hundred variations by a collective of stitchers and artists from around the world.

There’ll also be an exhibition at the end of the year at Bloc in Sheffield and more coming next year. Very exciting. I love being invited to take part in things.

Court: You’ve got loads going on! What’s the best way for people to keep up to date with what you’re up to?

Jan: Instagram is best. I’m @janxhopkins there or you can visit my website. If you want to get in touch, DM me on Instagram. I’m usually around.

Court: That sounds great! Thank you so much for your time. Your work is absolutely stunning and I’m so looking froward to having you in Definitions of Drawing II at Sunny Bank Mills next month.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: art, artist, coding, collaboration, drawings, exhibition, machines, Sheffield, technology

Comments