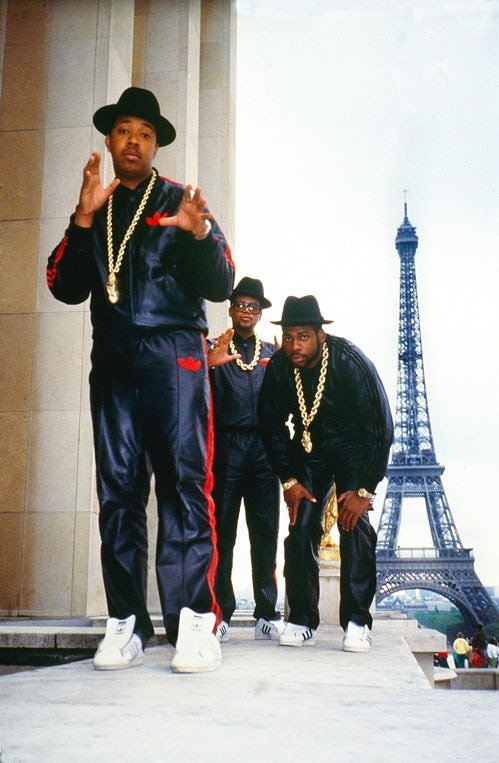

Credit: Ricky Powell

Compared to rock, rap seems to have a relatively positive relationship to consumer brands and commercialism. But the role of brands in rap music culture also tells us about a historically racist music industry that has excluded or under-invested in black artists, and about brands which only ‘support’ artists when the benefits of association are likely to outweigh perceived risks. While critiques of commercialism are overshadowed by celebrations of consumerism in rap lyrics, Public Enemy has interrogated the corporate exploitation behind such partnerships, perhaps most powerfully through 1991’s ‘1 Million Bottlebags’.

The tendency of mainstream music institutions to exclude black music until proven profitable, then to exploit black music until it has been drained of its value, has been demonstrated by tales of black labels and artists that have succeeded against the odds since the early days of recording. It is against this backdrop that rap artists have been wary of mainstream music institutions and particularly receptive to overtures from consumer brands looking to build relationships.

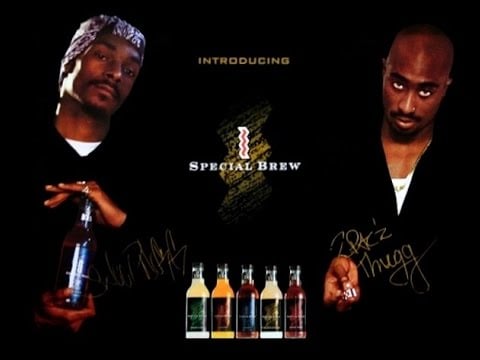

The relationship between Run-DMC and Adidas, following the release of Run-DMC’s 1986 single ‘My Adidas’, is perhaps the best known and most celebrated case of endorsement in rap, because it was an early and novel example, and because it was perceived as an ‘organic’ partnership, a moment of branding serendipity. Another early example which has not aged as well features beverage firm McKenzie River Corporation, which in 1988 turned to members of the underground West Coast rap scene to promote their St. Ides malt liquor. Over the following years, some of the biggest names from both coasts – Snoop Dogg, Wu Tang Clan, Notorious B.I.G. – appeared in the radio and television spots, rapping the praises of the malt liquor brand. As Eithne Quinn explains in ‘Nuthin’ but a “G” Thang: the Culture and Commerce of Gangsta Rap’, ‘Instead of incurring the common accusation of “selling out” from its core audience, the promoting of St. Ides actually worked to enhance rappers’ “keepin’ it real” image’ (Quinn 2005: 5).

Unlike Adidas, St. Ides was not a brand with an existing relationship to the hip-hop community, and some members criticised the endorsement of malt liquor by rappers. Quinn highlights the 1991 Public Enemy song ‘1 Million Bottlebags’ about the white corporate exploitation driving such partnerships: ‘They drink it thinkin’ it’s good/ But they don’t sell that shit in the white neighborhood/ Exposin’ the plan, they get mad at me / I understand, they’re slaves to the liquor man’.

As the lyrics suggest, the connection between malt liquor and rap culture reflected the strategy of malt liquor producers to target their marketing at poor, inner-city, mostly black populations – relying on a combination of poverty and alcohol abuse to popularise the product. While rappers moved on from endorsing malt liquor, the relationship to consumer brands continued to grow in the decades that followed, with sneaker and soft drink companies forging especially strong links. Sprite’s roster has included Kurtis Blow (1986), Heavy D (1990), A Tribe Called Quest (1994), KRS-One and MC Shan (1995), Nas and AZ (1997), and Drake (2010).

As Randall Kennedy writes in Sellout: ‘The Politics of Racial Betrayal‘, ‘When used in a racial context among African Americans, “sellout” is a disparaging term that refers to blacks who knowingly or with gross negligence act against the interest of blacks as a whole’ (2008: 5). For rap artists, commercial success or brand partnerships are not necessarily subject to accusations of selling out, as long as artists don’t use their newfound wealth to abandon the communities that nurtured them.

The role of racial authenticity in brokering the relationship between art and commerce makes it possible for rap artists to enjoy tremendous chart success, partner with consumer brands, and develop (into) global brands, all without being accused of selling out. However, looking back at its history, the relaxed relationship of rap to commercialism cannot be separated from racist treatment by the music industries and profit-seeking exploitation by consumer brands.

This is the third in a series of posts about the concept of ‘selling out’ in popular music culture in advance of the August publication of Selling Out: Culture, Commerce and Popular Music by Bloomsbury. You can read the previous post, which considers major labels, independence and the Clash, here. Follow @bethanylklein on Twitter and register for the 6th August online book launch here.

Filed under: Music

Tagged with: adidas, advertising, black, book, Brand, commercialism, corporate, exploitation, label, launch, Notorious B.I.G., Rap, rap music, selling out, snoop dog, st ides, white, wu tang clan

Comments