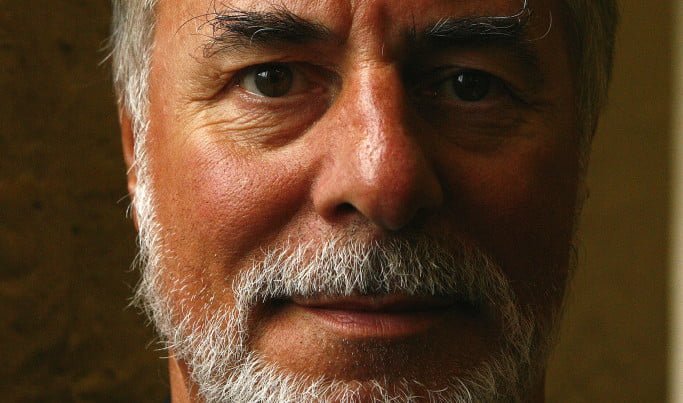

Barrie Rutter OBE, founder of Northern Broadsides and a self-declared ‘son of Hull’, took time out to chat about his resurrection of Richard III and being part of City of Culture ‘from day one’.

Barrie Rutter OBE, founder of Northern Broadsides and a self-declared ‘son of Hull’, took time out to chat about his resurrection of Richard III and being part of City of Culture ‘from day one’.

To begin at the beginning: “The company started here 25 years ago with a play, Richard III”, so today, the company are back to revive and retell this classic story. Rutter assured me that although “the basic text hasn’t changed, my word, it’s got different colours” this time around. Fitted out with a new designer, crew, and cast, this production will pay homage to Northern Broadsides’ heritage, without living in the past.

By chance, we were interrupted when the play’s producer, Barrie’s daughter, came to the dressing room. It was clear that “the Rutters [were] in town!” But beyond direct family ties, Rutter gushed about his fellow cast member Roy North, who also returns from the original production 25 years ago. “It goes beyond casting to fit the play. We’re family, so we’re both in it” once again. Rutter humbly claims: “I wasn’t going to be in it at first”, but “poetic pressure” from fans and family alike bring this theatrical heavyweight to the stage.

Yet, where Rutter began playing the eponymous villain many moons ago, he has since cast Mat Fraser in his place. He explained how the journey to find a Richard this time around was far from smooth. But upon meeting Mat there was a moment of relief and excitement: “This kid can play this.” From there, Rutter explained how they had to work on making him more of a monster, as well as making a spectacle of Fraser’s own disability: phocomelia. “He’s been terrific, very open about that. He’s very un-coy, because to him it’s not a sensation… But it is sensational, or can be sensational. I’ve been saying things like ‘don’t do that quickly, let it take it’s time’, because what we’re watching is a mini-work play of how you do something.” This casting seems to have brought another level to the emotion of the piece. And, beyond all of that, Rutter explained how Mat “is a mean percussionist”, perfectly complimenting the way in which this production “tells the story of the battles with instruments”. “The last thing I want is a bloody one-armed sword fight after two hours of slogging those words out”, Rutter thought upon playing the role himself.

To delve beyond the real, into the realm of Richard’s England, we discussed the character. Quite simply, Rutter is adamant that “he’s blatantly amoral”, but that this play is certainly not a “study in evil”. To balance the two aspects, Rutter places Richard alongside strong female characters who despise him, as the director “like[s] strong women on the stage”. But, as a “whacking-great part”, we, as an audience, must also like this ‘twat’ to an extent! “We all love our villains. They talk to us. They make us laugh!” Thus Rutter has directed his Richard to draw out the comedy that is intrinsically present in the piece. Through “the sheer audacity of the situations […] it can’t help but make you smile. But you know you’re being kicked as well.”

From discussing that “perfect Jacobean laugh that smacks you across the face”, I asked about editing the 400-year-old text. Rutter assured me that as “it’s a very long play”, he had done just that. “You’re entitled to edit it. But I’m very pleased with my edit.” Yet, as I’m a Shakespeare enthusiast, I feared for the welfare of some of my favourite characters and lines. Rutter poetically described that “it’s frogspawn. You can’t pick up a little bit of frogspawn, it all comes with it. So if you cut Margaret out, you cut all the links and all the frogspawn. So it’s a folly to cut Margaret.” With such poeticism in his own speech, I felt the text was in safe hands.

But beyond his own expressive flair, Rutter couldn’t help but punctuate his speech with eloquent quotes from this play that he clearly knows very well: “there are lines that sing out”. But, rather than intending to emphasise certain lines, the director seemed adamant that this production is not tied down to any specific interpretation or themes. “I’m not interested in that quasi-psychology four hundred years after the event—doesn’t interest me, never has done.” He describes such attempts as “sticking bits on with blutack”, “a shortcut” or “lack of imagination”. Thus, just as he spoke to me with Shakespeare’s own language, Rutter champions the written word in his production. “It is superbly written and crafted by Shakespeare”, so Rutter’s cast simply draw out what is already there. First and foremost, this is about “a passionate storytelling”, told with clarity, as if nobody had ever seen or heard this tale before.

Rather than strictly adherent to his own directorial vision, Rutter seemed to repeatedly return to the idea of giving his play up to the audience. When discussing actors doubling, he offered “poetry there if you want”, but claimed he, personally, “was not trying to say anything” in particular. Sticking loyally to the classic text for evidence and guidance, Rutter promised to “leave [interpretation] to the audience who hear it, to make up their own minds about how they think”. “They’ll do what they do, you know, they’re an audience and we have to keep our lugs on for reactions.” Rutter clearly has ownership and pride in his production, but repeatedly bows to the authority of both his playwright and his audience.

As “a classical company, with the pugnacity of the Northern voice”, Northern Broadsides promise to bring alive “a passionate, poetic, pugnacious, percussive …” (and as Rutter struggled for further p-words, I stepped in with…) plosive performance. “An evening in the theatre, which bears some relation to the passions of the play.” What more could you ask for?

Filed under: Theatre & Dance

Tagged with: Barrie Rutter, director, halifax, Hull, interview, Northern Broadsides, Richard III

Comments