Casual staff in creative industries, and why they are undervalued – opinion

December 14, 2021

The UK and Global Arts have had to do some serious self-reflection recently. Following George Floyd’s murder and the Black Lives Matter protests, Sarah Everard’s murder and the Women’s Rights protests, the climate crisis, increasing poverty, and the mass movement of people from around the world to find safety and refuge, all compressed by a global pandemic: we’ve had to really consider how the arts operates within an increasingly precarious world.

As Morvern Cunningham urges us, we need to “build back better”. We saw arts organisations begin to commit to anti-racism training, goals on diversity, pledges on working practices were made, and targets were set. The new Arts world was going to be a far more equitable place to work and make. Or so it seemed.

There have been some truly reflective and considered responses to the calls from art workers and artists for positive change. Whilst we’ve seen some organisations consider how the work they promote and create can be more representative, we have been shown examples of organisations not considering how their organisational practices intersect with racism, sexism, ableism, heteronormativity, and classism abound.

Whilst I firmly believe it is important that positive action is taken towards artistic representation, I also believe it is equally important that these sentiments continue within organisational practices. The arts industry is notorious for advertising staff positions that are based on minimum wage (£8.91/hr), and zero-hour temporary contracts.

The ‘Trades Union Congress’ published an article in 2019 highlighting that zero hour contracts disproportionately impact BIPOC+ workers, who are more likely to become stuck in temporary, low pay and insecure work and suggested that zero hours contracts have also been linked to “…trapping women of colour on low pay”.

Furthermore, studies have shown overall that women also make up the majority of low paid roles (with 24% of women earning less than the real living wage), people with disabilities are facing a significant pay gap , as do LGBTQIA+ people.

Yet despite the build back better mentality within the arts we signed up to, organisations are still not implementing a living wage (£9.90/hr) for workers across the board.

Campaign group ‘Disabled People Against Cuts’ during a 2012 protest. (Source: Left Unity)

So why are organisations delivering anti-racism training, setting goals on diversity, and making pledges to do better, whilst also employing people in ways which maintain and encourage inequalities?

In 2018 Creative Scotland, the arms-length Government funding body, stated that all regularly funded organisations (those that receive 3 years’ worth of financial support), were to “commit to pay a Living Wage… to all core workers”. However, in a recent response asking why they were advertising positions below the real living wage, a Glasgow based theatre stated in response:

“We do pay a small % of casuals the minimum wage of £8.91 regardless of their age. This is in line with our Creative Scotland RFO agreement, with the core team paid a living wage. We have aspirations to pay living wage levels across the board as soon as we’re financially able.”

They are not alone in their questionable employability practices. Several arts organisations advertise for temporary Christmas workers (many of whom are expected to work on Christmas Eve, Boxing Day and New Years Eve), which offer their new employees nothing more than minimum wage, unconfirmed hours and temporary contracts. Perhaps this is legitimised by not considering these staff members as ‘core’. Of course, without these temporary workers, pantos and Christmas shows couldn’t open, audiences would not be welcomed, and tickets would not be checked. Most theatres wouldn’t be able to generate their only reliable source of income for the year. Organisations within the Arts seem to be recreating the capitalist structures which many artists fight against within their work.

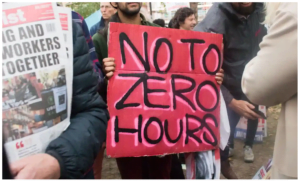

Protests against Zero Hours Contacts, 2018 (Source: Amer Ghazzal, Rex, Shutterstock)

This is not a problem isolated to Scotland. A Salford-based Theatre, advertised for temporary front of house staff in October, and despite being near Manchester one of the most expensive cities in the UK, offered just minimum wages. Theatres across the UK wouldn’t be able to function sufficiently without these temporary festive workers – so why do we not pay them more?

Ironically, this same theatre has staged a play which focuses on the impact of unpaid care, austerity, and inequalities, whilst simultaneously not implementing a living wage for all the staff working the show. How can organisations claim they are tackling inequality without looking to the most precariously employed within their structures?

One potential solution to this comes from funding bodies themselves. Organisations often resort to building businesses on hierarchical organisation structures, where those at the ‘bottom’ feel the impacts of shrinking budgets the most, whilst those at the ‘top’ may not.

However, if funding bodies stipulate that those organisations pay their workers a fair living wage; the exhibitions, productions, screenings… etc which which are put on, are not done so at the expense of those employed.

Protesters outside the National Theatre, August 2021, calling for better payment terms for casual workers. (Source: The Stage)

Lyn Gardener wrote extensively about the need for theatres to slow down, how organisations constantly rushing to stage work may in turn have detrimental impacts on the people they encounter and employ. Without a slow, sustainable and fair approach, organisations will continue to squeeze their budgets dry and fail to support their staff.

This idea of slowness is one we need arts organisations to buy into, with the support of funders. This would allow the public to step into a theatre, a gallery, a cinema knowing that every member of staff there was being cared for even if it meant fewer exhibitions, performances, or screenings in the long term.

As an 2020 American study found, organisations which truly embed meaningful equality practices make larger profits, retain staff for longer and are more innovative. The results for Arts organisations could be even more phenomenal if perhaps they slowed down, just a little.

Follow writer Rosie here, on their twitter, instagram and website to see what they’re up to.

***

The views within the article reflect that of the author and not necessarily the TSOTA’s as a whole.

Filed under: Politics

Tagged with: arts, casual staff, creative industry, discrimination, fair pay, Glasgow, minimum wage, Pay gap, Salford, staff, temporary contacts, zero hours contacts

Comments