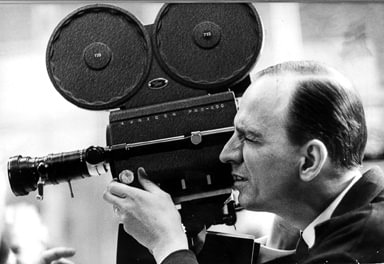

Source: sydsvenskan.se via Wikimedia Commons

If asked, the average film enthusiast would probably list Kubrick, Scorsese, or Hitchcock amongst their favourite directors. A name often missing amongst the all-time greats is Ingmar Bergman, who many people may not have even heard of. Born in Sweden in 1918, and blatantly inspired by his recent Scandinavian predecessors such as Ibsen and Strindberg, Bergman created innovative and profound drama. 2018 marks the centenary of Bergman’s birth and to celebrate his exceptional work, the Watershed in Bristol screened a selection of his best films.

Persona (1966) is not the best place to start if you are new to Bergman. Whilst it is undoubtedly one of his greatest films (if not one of the greatest films), its presentation is exceptionally avant-garde, and many may find it difficult to watch. In the film, a nurse is assigned, for the summer, to an isolated seaside cottage with an actress who has taken an unexplained vow of silence. Whilst at the cottage the nurse reveals her past to the actress and experiences an identity crisis. I made the hilarious mistake of bringing a friend who had never seen a film by Bergman to the Watershed’s screening of Persona, and for the rest of the evening, like the actress, she was speechless.

In a way, Persona is a perfect example of Bergman’s cinematic achievements, but don’t let my friend’s reaction put you off. Persona, along with many of his other works, reflects a personal crisis within Bergman, which is a testament to why his films are so profound. They come from a place rooted deep within the auteur, which explains why the film moved me, and my friend felt attacked by it. It digs deep into your subconscious id and makes you question not only the film but yourself.

Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) offers a slightly lighter entry into Bergman’s work. A comedy of Shakespearean regard, it still has many of the darker themes of Bergman’s other films. However, this film benefits from a light tone throughout and has many genuine laugh-out-loud moments that even a modern comedy fan can enjoy. Still, even in this early comedy, Bergman is unafraid of being innovative. The film grapples with challenging themes such as sex, polygamy, and suicide, and yet manages to sustain Bergman’s sophisticated taste and avoids being crass. I regard this film’s comedy as a predecessor to Monty Python’s silly comic style. Those that enjoy the Python films will love Smiles of a Summer Night.

Via Wikimedia Commons

Set at the end of the 20th Century, but one of Bergman’s final films, Cries & Whispers (1972) shows the lives of three sisters and their maid who have gathered to look after one of the three sisters, Agnes, who is dying from cancer. The film is shot in colour and proves that Bergman is capable of using colour for a purpose rather than profit or cosmetics. The striking crimson colours in the scenery and editing style reflect the visceral and intense moments that we experience throughout. Cries and Whispers is my favourite Ingmar Bergman film because, from a filmmaker’s perspective, it is perfect. The choice of sound, colour, dialogue, and cast are all artistically justified, creating an experience that, similarly to Persona, is emotionally exhaustive yet inescapably fascinating. Cries and Whispers is likely Bergman’s most distressing film, however, it is clear that throughout his career he refined his craft. I consider it one of the greatest films ever made by the greatest film director who ever lived!

Many know Ingmar Bergman for his collaborations with actor Max von Sydow, who appears in Bergman classics such as The Seventh Seal (1957) and Winter Light (1963). Incredible performances from actors like Sydow, Liv Ullmann, and Gunnar Björnstrand succeed in bringing Bergman’s films to life. These actors, with Ullmann being a personal favourite, have an intriguing beauty and subtlety to their performances. Bergman had a fascination with the human face and as a result became a master of filming them, and through this, he allowed avid cinema-goers an opportunity to share in his fascination.

Bergman’s films are selfish, they do not reach out to appease the viewer. Instead they present themselves as an enigma, inviting you to investigate, and as a result, discover something deeply profound about life. Whilst he is admittedly a difficult cinema auteur to get to grips with for the average film fan, Ingmar Bergman has cemented his place as an all-time great, worthy of an entire season at the Bristol Watershed in preparation for his centenary this coming July.

Filed under: Film, TV & Tech

Tagged with: bristol, Celebrating Ingmar Bergman, film, Ingmar Bergman, the Watershed

Comments