“Europe is a place everchanging. Sometimes stunningly beautiful, sometimes dreadfully cruel. What will the next changes of Europe be? It is upon all of us to answer, and everyone will have a responsibility for this answer. Will this be a Europe of the few or a Europe of many? How will we react to the coming challenges, which can only be solved together? Climate change will only be solved by empathy and working together, which Stephen Hawking pointed out before his death. And so it will be with the pandemic growth of coronavirus, too. Will Europe wear the dress of iron barb again? Or will it be another future for us?” – Julya Rabinowich, March 2020

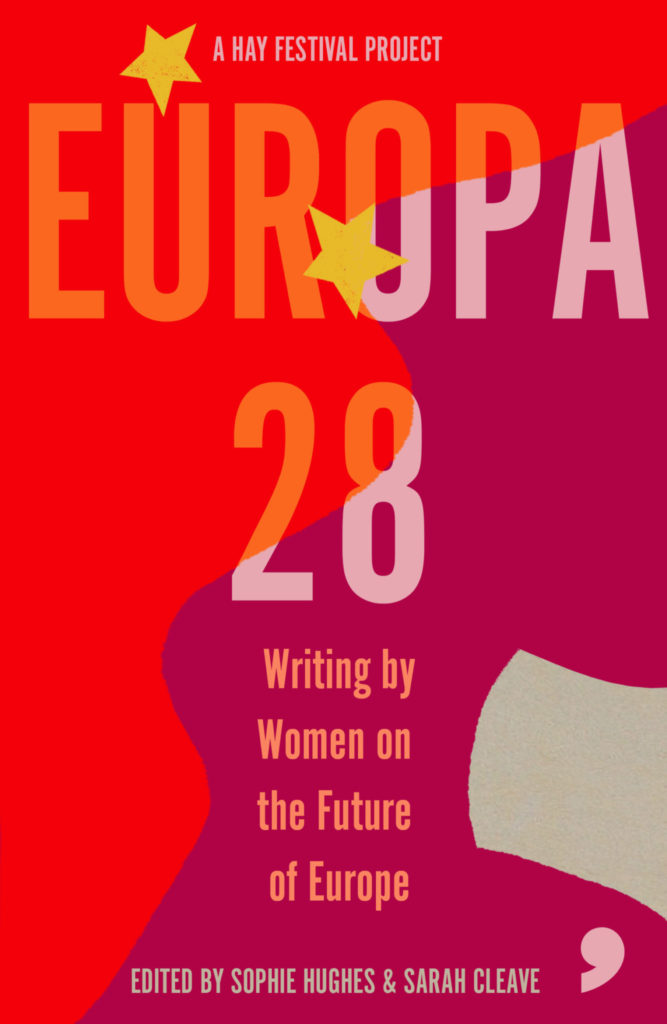

The following essay is taken from Comma Press’ latest publication ‘Europa28: Writing by Women on the Future of Europe’, a project in partnership with Hay Festival. This is a collection of 28 essays and short fiction by 28 women writers, artists, scientists and entrepreneurs from 28 EU countries (including the recently departed UK), each writing their vision for the future of Europe.

Europa28 is out now and available from all good bookshops, online retailers and direct from https://commapress.co.uk/books/europa28/

AUSTRIA

‘Cracks in the Ice’, Julya Rabinowich

The Europe we know today, the Europe of common factors, is still young. Almost as young as the people who have unthinkingly received its wealth of opportunities, laid in their cradles as a gift from the fairies. The old Europe is shifting away, apparently blurring in the shadow of memory, almost disappeared from the consciousness of advancing generations. That world marked out by borders, in some cases insurmountable, laid down in Europe between East and West. Those heavily-guarded, barbed-wire-reinforced borders, in those days, scaled on pain of death. Borders with dramatic escape attempts, with soldiers and earth roiled-up in death strips. Patrols and the hoarse barks of guard dogs.

Berlin was the beating heart of this Europe-wide fragmentation, a terrifying and fascinating hybrid of East and West. West Germany and the GDR. Linked by well-guarded cracks between the worlds. Checkpoint Charlie was a spaceport from which to leap into another galaxy. On either side of that border, people were largely clueless about what lay beyond. Crossing the worlds was like leaping into a black hole. The Eastern Bloc ceased to exist at the Iron Curtain. The world had frozen in the held breath of the Cold War, and Vienna was a small, much-visited island between the two. It was during this time that the tides carried my little family to Vienna, where we got caught up like driftwood. And luckily so.

When I was nineteen, this apparently stable state of torpor began to tremble. Bricks loosened from walls and crashed to the ground, falling across decades-old lines drawn to divide the land both on the map and in its real form. Europe as we knew it morphed bit by bit into a new, open, common Europe. Shortly after the Wall fell, I moved to Berlin for a while. The great euphoria, the intoxication of freedom, the creative dialogue along the Wall are experiences forever anchored in my mind – brighter, more intense, uncanny and exciting than almost anything else. And I have not forgotten it my whole life long, that atmosphere of starting anew. With all the unexplored, and yet, common factors.

Back when the first sections of the Wall broke down and contemporary history was written – tangibly, palpably, co-operatively – Europe was not yet where it stood a few years later. What had once split Germany in two was surmounted. Great days lay ahead of us, we thought at the time.

What lay behind us, though? That steel fencing was not the first of its kind.

Europe has donned its barbed-wire dress several times. People prevented from leaving their country died, chased down in hiding places, driven together like animals, degraded, de-humanised, emaciated, skin stretched taut over bones. Children playing in piles of corpses, seeking protection from the wind and weather. That too is our European past. Never again, it was said back then, and today we gaze once more into the hideous face of this de-humanisation, born again, albeit not derailing at full speed. Not yet. Our common Europe is thus the response to the destruction wrought by the Holocaust upon the European body. It is intended to place our common factors over those that divide us. It is intended to tear down borders of the mind and our territories. It is intended to unite and enable common growth. It is intended as the opposite of what once was. The idea is beautiful. But also, a little delusory. The ice of civilisation is thin, too thin to carry out test drillings of a political nature. The ice is thin and its cracking is clearly audible in times like these.

The ability for empathy is what might help humankind survive. This aggression and waning of empathy, incidentally, are the deadly sins that Stephen Hawking regards as a threat to humankind’s survival as a species. What can be done when inhibition levels fall while sea levels rise? Unfamiliar tides await us. The safety and security to which we are so accustomed – they are not guaranteed. They are a mere promise that might perhaps no longer be kept if the fronts become entrenched. We only have this one world, and at the moment, Hawking’s recommendation to resettle in space is unachievable science fiction.

The waters are rising. The inhibition levels, however, are falling.

Stephen Hawking was a scientist of great genius, whose theories were well-founded. I am merely one writer among many. And yet I want to believe in a better world and a better outcome. I want to believe in humankind. And in its ability to develop further. I want to believe that we might not develop only weapons capable of bringing us death and extinction a hundred times over. We can also develop a way of cooperating, a culture of dialogue that might secure a different future for us.

And now, Europe? What once was divided is now expected to grow. Another thing growing, however, is the resistance against uniting. And nationalism is on the rise too. The nationalism that the European Union set out to end, and likewise the nationalism whose political representatives have often developed a remarkable closeness to Russia, particularly to Vladimir Putin. Presumably not without reason, when we keep finding leaks about monetary transfers from Russia to parties like Marine Le Pen’s, for instance.

What might help repair this rupture? What might put a stop to this fragmentation?

We need a Europe of affinity. A Europe of empathy. A Europe of cooperation and equal opportunity. Only with firm ground beneath our feet can we reach for the stars – including those set against a blue background. We need a Europe of self-confidence. Of moral conviction. And that’s where the next question arises. The much-touted European values – what exactly are they? Worshipping the past while disregarding its crimes? Or recalling what makes humans human: compassion and responsibility? Recalling what makes Europeans European: the Enlightenment and humanism? And if that’s the case, how do we now deal with the deaths in the Mediterranean? The lifeless corpses of children floating on the water of our next beach holiday – do we suppress the thought of them, do we prevent them?

How does Europe explain this failure on its borders? How do we explain the reception camps in Greece, the starving refugees in Hungary, where the state refuses to provide them with food so as to encourage them to leave the country? How can the European Union watch Viktor Orbán’s actions, the destruction of press freedom, the unleashing of darkest instincts – right-wing populists always resort to the darkest of instincts, a simple, effective and cheap solution that will cost us all dearly.

I am writing this piece in Vienna, the city that was always poised between East and West, a Checkpoint Charlie of a different kind, a political fulcrum in the style of ‘The Third Man’ and a neutral site of the United Nations. But also a country that has veiled its complicity in the Holocaust, unlike Germany – Austria with its myth of being Hitler’s first victim – and at the same time a country that has made great contributions in the humanitarian sector, the country that gave me a new home and that I regard as my country, the country which I therefore demand does the right thing more firmly than I demand of other places not as dear to my heart.

I love the narrow, winding streets around St Stephen’s Cathedral, I love the magnificent buildings along the Ring, the rustic taverns selling local wine, the cool museum quarter, the range of culture on offer, the literature and the biting wit, and I love the safety and security it still provides. And yet: as I sit at my desk and look out of my window, I see Stumbling Stones, the brass cobblestones inscribed with the names of the Jews murdered after 1938, remembrance cast in metal outside the front doors of their former abodes. And right next door to me, someone has drawn a swastika in the dusty glass of a flat being renovated. That is the reality of Europe at this moment. That which we believed surmounted has returned. To date, it is erratic, blurred, not yet fully materialised; the sleep of reason is still in the act of producing its monsters.

We want to be a moral instance, an embodiment of Never again, we want to be enlightened and humanist? Then we must tackle all these issues. Earnestly. Decisively. There is not much time left to act. Already the structure is swaying, already bricks are falling from facades once thought solid, already the ice is cracking beneath our feet. Listen very closely. You can hear it now, at this moment. We want to be human and remain so? Good. Then let us take action. Now.

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire

Julya Rabinowich was born in St. Petersburg in 1970, but has lived in Vienna since 1977, where she also studied. She works as a writer and columnist, and also worked as an interpreter until 2006. She is the author of ’Splithead’ (2008), which won awards including the 2009 Rauriser Literaturpreis, ’Herznovelle’ (2011), nominated for the Prix du Livre Européen, and ’Dazwischen: Ich’, her first book for children. Julya has been awarded the Friedrich-Gerstäcker Prize, the Österreichischer Kinder- und Jugendbuchpreis award and the Luchs Prize (Die Zeit & Radio Bremen), and one of her works was selected among the seven best books for young readers (Deutschlandfunk). In 2019, she published the children’s book ’Hinter Glas’.

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: austria, book, climate change, Comma Press, europa 28, europe, everchanging, future, holocaust, nationalism, nazi, new, politics, publication, stephen hawking, text, vienna, war, women, writers, writing

Comments