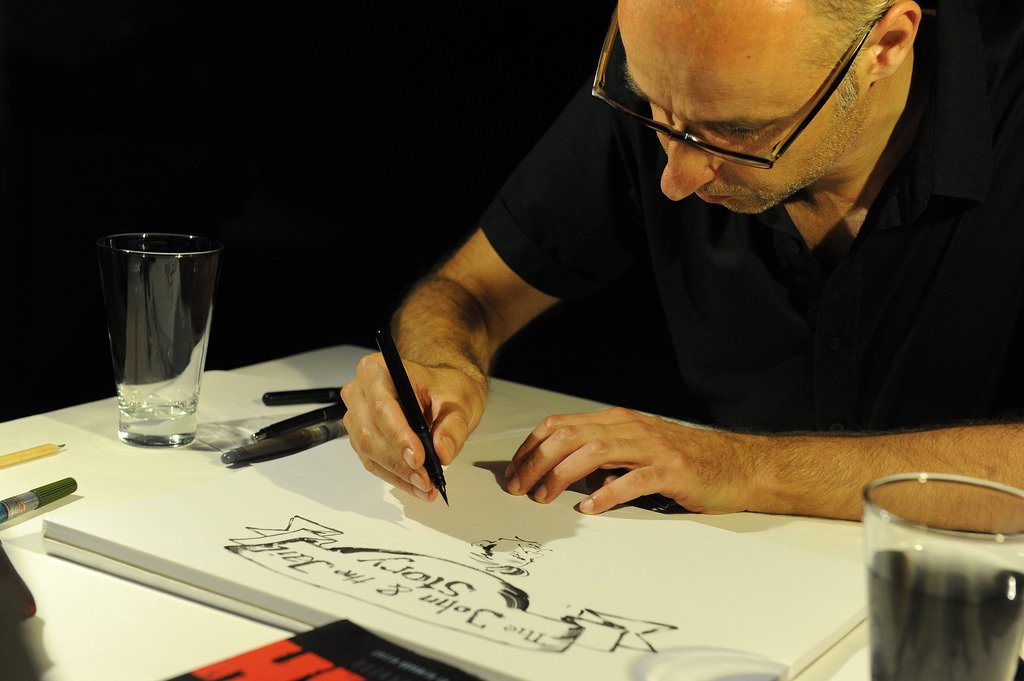

On the back cover of Nick Cave: Mercy on Me, Cave himself describes the book’s author, Reinhard Kleist, as a “master graphic-novelist and myth-maker”. This is a reputation Kleist has cultivated in a career spanning over two decades, in which he has solidified himself as an innovator of the graphic novel form.

Much of Kleist’s recent work has been focussed around the exploration of icons. From Johnny Cash (Johnny Cash: I See Darkness, 2006) to Fidel Castro (Castro, 2010) – the world of music to the world of revolution – the author treats his subjects with subtlety and attentiveness, creating a lucid picture of the lives and environments of his characters, and adding to the legends that these fascinating figures carry with them.

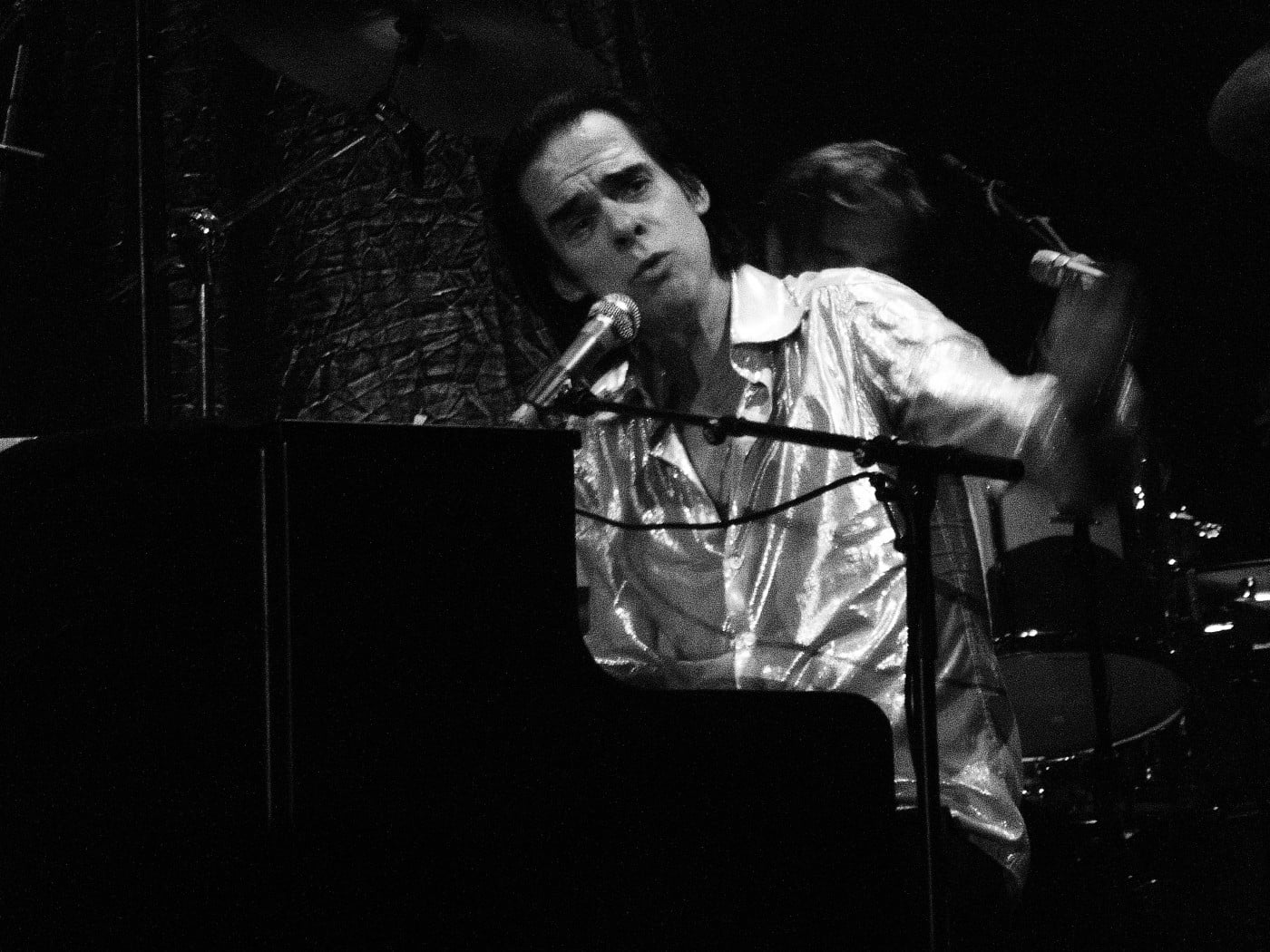

With his most recent work, Nick Cave: Mercy on Me, Kleist has returned to the subject of the enigmatic musician, focussing his attention on the singer and writer Nick Cave. The graphic biography charts Cave’s rise from his angsty teenage years in Australia to the renowned vocalist and lyricist of bands like The Birthday Party and Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds. Much like Kleist’s other subjects, Cave is just as much an icon as he is an iconoclast, and Kleist depicts him as a complex, contrarian and, especially in the early days, not entirely pleasant person. But this gives a hint to why Kleist found his story so interesting; with so many convolutions and contradictions in his life it was bound to make a captivating tale, and perhaps one for which the restrictiveness of text does not suffice.

The first depiction of Cave comes just a few pages into the first chapter: a shadowy, gun-toting, and eerily still individual. We get our first glimpse into the character of this mysterious figure as he fires a ruthless, two-barrelled blast into the gut of a seemingly innocent man. It becomes clear that the victim of this attack is a Cave-created character, the protagonist of the Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds’ song “The Hammer Song”, from which the first chapter borrows its title. This is the first instance in Mercy on Me of Kleist using a kind of meta-narrator that fluctuates between characters from Cave’s songs, as well as from his literary output, blurring the lines between fiction and biography, and providing an adversary for Cave to battle against – his own unfortunate creations, disgruntled at having been killed off by their author.

Just like the narrator of “The Hammer Song”, the narrator of the first chapter of Mercy on Me sees visions of angels, beautifully depicted by Kleist, with velvety wings and white eyes turning into hissing snakes – a paradox of demonic holiness not uncommon in “Cave World”, as Cave puts it in the blurb he wrote for the cover of the book. Though it may seem slightly egotistical to name an artistic landscape such as “Cave World” after oneself, Nick Cave is somewhat of a polymath, whose distinctive style has spread from music to novels and film, and now to graphic novels, so perhaps the coinage is appropriate.

A couple of pages on from this violent introduction, we see a completely different version of Cave as a cocky teenager, his scrawny frame almost skeletal. From this point we witness the character’s volatile transformation from anonymous kid to rock star. One of the most interesting aspects of the book is the concept of identity being forged by the individual, rather than external forces. Kleist paints a picture of Cave as a man who decided who he wanted to be, then went out into the world and made that vision a reality – though seemingly to the detriment of the lives of those around him. This duality of Cave as a talented artist, but difficult bandmate and absent lover, gives an otherwise emblematic character an emotional edge, making him appear as just another flawed human being, rather than the impenetrable icon.

The way Kleist draws Cave at every stage of his life shows how this transformation manifests in his physical form, from punk teenager, to the suited, slicked-back Cave of the present. It is not, however, only the man who changes, but also the world around him, and Kleist does an equally compelling job at portraying the environments his character steps into. The 1980’s post-punk scene of London is particularly immersive, with the meticulously drawn band posters and multifarious extreme hairstyles providing a vivid layer of detail.

The oscillations from Southern Gothic vignettes to biographical facts, leaps from Brazil to Geneva and beyond, and the generally erratic structure of the narrative, all work to create a confounding world of ambiguous boundaries. This scattered, jazz-like approach to narrative is a common feature of Kleist’s work, serving to encourage the reader to find their own meanings. Kleist put it frankly in an interview with his publisher SelfMadeHero stating, “Sometimes you have to confuse the reader a little bit.” This is a simple but pertinent admission, as with confusion comes intrigue, drawing the reader deeper into the chaos of the work.

This is a dynamic and inventive graphic novel, and an impressive addition to Kleist’s body of work. It once again shows how he has the ability to tell a variety of diverse stories. The differences between Mercy on Me and a book like Castro are myriad. Where the contentious story of Castro required, to a large extent, a more sober, journalistic approach, resulting in a more constrained narrative and panel-structure, the subject matter of Mercy on Me allows for the form to break down into unrestricted, dreamlike sequences, floating in space or driving through the apocalypse with Robert Johnson in the passenger seat – and it’s these sections that make Mercy on Me so fun and enjoyable. The book has a tendency to verge into sycophancy in parts, and sometimes the narrators that Kleist employs can come across as proxies for his own admiration, which may be off-putting for non-obsessives. Otherwise, Mercy on Me is a great extension of “Cave World”.

Filed under: Art & Photography, Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: Biography, Graphic Novels, nick cave, Reinhard Kleist

Comments