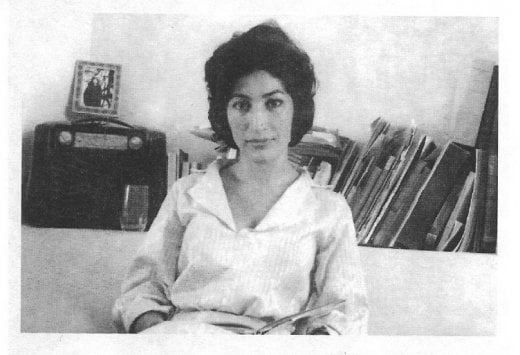

Love in Its Rawest Form: a brief look at the work and life of poet Forugh Farrokhzad

August 26, 2020

I recently discovered that repeating a passage from a book in my head can help me fall asleep, distracting my brain so my body can shut down. The passage isn’t always the same, but the author is. Other authors would do, but her collection of poems has been sitting on my bedside table since the first time I tried it.”

By this time I was already in love with Forugh Farrokhzad’s work, but this functional quality seemed to come about by accident, suddenly realising that her words, both in rhythm and subject, have a calming effect on me. Her history drew me to the work in the first place, and to my delight her poems reflect how she is described by the people who have written about her. Radical, beautiful, sardonic, lyrical; contemplative about life and hurt by it, and combative about her place as a woman in Iranian society.

Farrokhzad was an urbanite, born in Tehran in 1935. She was precocious, reading whatever she could, and was determined to compete with her brothers, or the boys from her neighbourhood, wherever her family settled. Married at 16, her husband was progressive enough to encourage her obvious poetic talent. The marriage wouldn’t last, but her formative years benefited from this relatively unusual relationship; it was not only creative freedom she experienced, but emancipation from Iran’s corporeal oppression of women.

Sholeh Wolpé (one of her translators, please see reference at the bottom) describes how, during her marriage, Farrokhzad began wearing “revealing” clothing, garnering disapproval from the local men. Wolpé says, “Forugh is pushing the limits as she will continue to do throughout her brief but eventful life.”

Iran in the 20th century was constantly in turmoil. For women, there was an ebb and flow of social freedom, but it was precarious and depended on who ruled at the time. Reza Shah, whose son would be the last Shah of Iran, banned the veil in 1936. It remained in law under his son’s rule, but the law was hardly enforced and there were still certain expectations of women. After the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the religious conservatives would enforce traditional dress.

A formidable artist, the Iranian intelligentsia could not ignore Farrokhzad, but there were many who tried to discredit her. Her love affairs became the focus, rather than her revolutionary work, which contributed to a modernisation of Persian poetry. Rather than archaic raptures about women’s breasts, her lyrics waxed sensual about the male form and the pleasure two parties can derive from it, especially herself. From one of her most infamous poems, ‘Sin’:

“I poured in his ears lyrics of love/ Oh my life, my lover it’s you I want./ Life-giving arms, it’s you I crave./ Crazed lover, for you I thirst.”

Her relationship with Ebrahim Goldstein, Iranian filmmaker and writer, was well-known, and many of her critics had the audacity to claim that he was the real author of her work. More than anything, this exposed the inadequacy of her detractors, who clearly believed the work was significant. She was bullied and undermined, but reading her now, it’s easy to understand why she posed such a threat.

The Iranian media were in part responsible for the vile and constant public shaming she received. Though she struggled with this aspect of her fame, she always hit back, whether it was in her work, letters, or in interviews. ‘Only Voice Remains’ is a brilliantly bitter example of Farrokhzad using her poetry as a weapon. Epic in its scope, she had no intention of veiling her anger, haranguing the press in between reflections on the experience of living:

“The Earth repeats itself in space, air tunnels/ become connecting canals and day changes/ to an entity so vast it cannot be stuffed/ into the narrow imaginations of the newspaper worms.”

Despite her strength, there is a noticeable weariness – she was tired of having to prove herself while her male contemporaries produced inferior work, free of the barriers she had to break through with every step. But, regardless, she never stopped. She spoke only from her own heart and mind (“… my heart’s charter cannot be drafted/ by the provincial government of the blind.”), but her words empower anyone who is interested in listening.

There has always been revolutionary art which simultaneously criticises backwards politics and touches the soul, but Farrokhzad’s work is different. Rarely does art such as this come from so deep within a person’s core, where political action and spiritual advancement depend on one another for the artist to succeed in her fight. There are so many fights going on now, and it can be tiring and depressing just to follow what’s going on. That is why, when we have time to disconnect from the world, we have to bury ourselves in the work of people like Forugh Farrokhzad.

It’s a cruel joke that some of the artists who change us are the ones who find life the hardest to enjoy. At age 20, in 1955, having already released some of her best work, she was admitted to a psychiatric clinic and given electroshock therapy after a nervous breakdown. She recovered, but the remaining years of her life were spent battling the world and herself. The first verse of her poem, ‘Forgive Her’, perfectly expresses the struggle between her urge to fight and her tiredness at having to do so.

“Forgive her./ Sometimes she forgets/ she is painfully the same/ as stagnant water,/ hollow ditches,/ foolishly imagines/ she has the right to exist.”

After she meets Ebrahim Goldstein in 1958, she goes to England to study film production. In 1962, she films ‘The House is Black’, a stunning film which humanises the people of a leper colony with the kind of spiritual and radical approach she was known for as a poet. The 20-minute experimental documentary is one of Iran’s greatest films, and is a precursor to the revered Iranian New Wave. Abbas Kiarostami would name his film, ‘The Wind Will Carry Us’, after one of her best poems.

Forugh Farrokhzad died in 1967 in a car crash. She was 32. Like all great artists who die young, their lives are a reminder of how much we can achieve during what might otherwise seem like a short amount of time. Read her poems, and what you will find is a person who believed. In her work, herself, life, the spirit, and especially love. No matter how much she had to fight, Farrokhzad believed in the power of love in its rawest form, and urged us to do the same:

“Yes, so love begins,/ and though the road’s end is out of sight,/ I do not think of the end/ for it’s the loving I so love.”

Source of all translations: ‘Sin: Selected Poems of Forugh Farrokhzad‘ edited and translated by Sholeh Wolpé (University Arkansas Press)

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: artist, courage, Forough Farrokhzad, Iran, Iranian, opressed, opression, poem, poet, revolutuion, sensual, sexuality

Comments