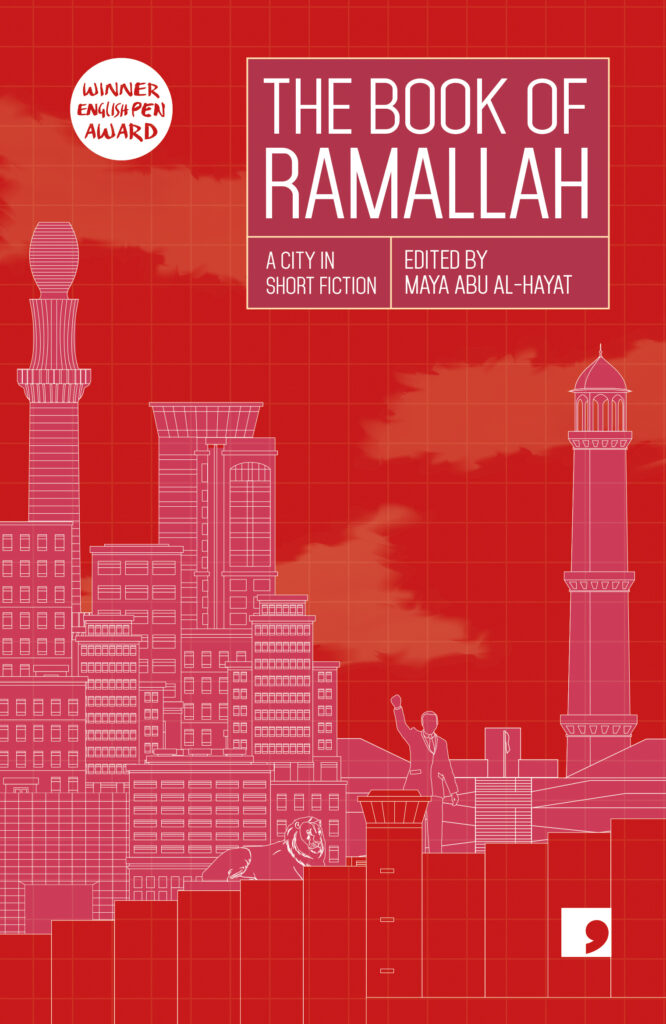

The following story is taken from ‘The Book of Ramallah: A City in Short Fiction’ edited by Maya Abu Al-Hayat, published by Comma Press (2021).

Unlike most other Palestinian cities, Ramallah is a relatively new town, a de facto capital of the West Bank allowed to thrive after the Oslo Peace Accords, but just as quickly hemmed in and suffocated by the Occupation as the Accords have failed. Perched along the top of a mountainous ridge, it plays host to many contradictions: traditional Palestinian architecture jostling against aspirational developments and cultural initiatives, a thriving nightlife in one district, with much more conservative, religious attitudes in the next. Most striking however – as these stories show – is the quiet dignity, resilience and humour of its people; citizens who take their lives into their hands every time they travel from one place to the next, who continue to live through countless sieges, and yet still find the time, and resourcefulness, to create.

Secrets Stroll the City’s Streets

Ahmed Jaber

Translated by Adam Talib

‘Good morning. God give you strength.’

‘And to you,’ the street-sweeper replied to the young woman, then silently to himself: ‘God bless your every step.’ On a street corner in downtown Ramallah, this scene is repeated every day at the same time, with the same characters – Abu Ibrahim and the young woman – the only things that ever change are the date and what the woman is wearing.

Abu Ibrahim was two months into his sixth year working as a street-sweeper in the district. He woke up early each morning and greeted us all, rousing the roosters and imploring the skies, before turning to me, Ramallah, to say, ‘Here we go, Gorgeous.’ Then he would start sweeping my streets and alleys, whisking away any trace of the night before and preparing me for the day ahead. Cloaked in my new finery, I watched as the houses stirred, their windows thrown wide like eyes, their doors yawning. It was finally my turn to wish the people a good morning.

Every day, I played the goddess, observing my people closely and exchanging secrets with them. For example, today the young woman abandoned her heart on a street corner – I won’t tell you which one because that’s strictly between me and her – before heading on her daily visit to the shops that squat hidden behind the brand-name outlets. When I lost track of her, all I had to do was look for the clashing bright colours she was known to wear and then I found her easily. She went from shop to shop until she’d finished her rounds and then before returning home she went back to that very corner, the one that only she and I know, and picked her heart up again. Then she ran back home. This morning, she had stopped by her usual coffee guy – in Ramallah, everyone has their favourite coffee guy – and although she knew his coffee wasn’t the best the city had to offer, she and the other customers liked it enough and the prospect of changing their routine was too much of a drag. That’s all there was to it. She had simply become a regular.

The coffee guy didn’t have time to chat with his customers. He barely had time to ask them what they wanted and to hand them their order because the whole operation took no more than three minutes. He allowed himself to ask each of his customers just one question and that was how he heard about the day’s news. His customers were a pretty diverse group: they included economists, politicians, engineers, businessmen, labourers, students, and so on. He also asked everyone how they were doing and everyone gave the same answer, ‘Good, thanks.’ He always hoped that one of them – man or woman – would ask the same of him but they never did. I, Ramallah, asked him all the time, however. Every evening as he wiped down his coffee cart before shutting it, he would answer me: ‘I’m fine,’ he’d say and then he’d smile and whisper to me. I’m not telling you what he said – it’s a secret – but it always made me laugh.

After he finished his morning shift, Abu Ibrahim walked down Rukab Street, with a slight but perceptible limp, toward the coffee guy because he was a regular, too. He peered into the shop windows as he strolled past before a poster stopped him in his tracks. Well designed with eye-catching red text, the poster advertised a music festival that was happening in a few days. After he’d noted all the details, the time and the location, which like most musical and artistic festivals was in the area between Rashid al-Hadadin Square and the Ramallah Cultural Center, he recalled an event from ten years ago.

Abu Ibrahim calls his sister on the phone. ‘I’m taking you to a concert tonight.’

‘A concert? Are you serious?’ she asks. ‘Why me? Why don’t you go with your wife?’

‘Because this concert is for us. We’re the ones who used to dance to Boney M. songs in the 70s.’

‘Boney M.! When?’

‘Tonight. They’re here for the Palestine International Music and Dance Festival. We can relive our days of dancing to ‘Daddy Cool’ and ‘Rasputin’. We can be kids again.’

The band comes out on stage to cheers and applause that lasted far longer than they expected. ‘We love Palestine!’ Maizie Williams shouts into the microphone. ‘We love you all – people of Palestine! We’re going to take you somewhere far away. To the sea!’

Every detail of that night will remain clear: how he loses his voice; how he dances like he hasn’t danced in years, holding his sister’s hand like he did thirty years before. He will never forget the moment when the power goes out and he laughs and screams, ‘Welcome to Palestine!’ Then the electricity kicks back in and with it all the colourful lights, the euphoria, the twirling plaited hair, and the Casio watches all the kids are wearing.

Abu Ibrahim emerged from his daydream and carried on walking. He saw grains scattered carefully on the street corner. He always wondered who it was who came to leave wheat for the pigeons. That person created an image for anyone who walked past, a painting of pigeons calmly eating their meal, unstartled by the footsteps on the pavement. He still didn’t know who this person was, he realised, and at that moment he resolved – like someone deciding on a new adventure, if you could call it that – that he would wake up even earlier the next morning in the hope of meeting the pigeons’ friend.

The next morning at 6am, Abu Ibrahim steps out of his house into the darkness and heads toward the corner where the pigeons’ friend leaves wheat for them. He looks at the face of the sky, which is still freckled with stars. He sees an orange light peeking out from a bakery nearby so he runs over quickly to say, ‘Good morning, neighbour,’ and then returns to his route down Rukab Street. He looks over his shoulder at the streets he has to sweep and says to them, ‘I’ll be back, Alleyways. I just need to satisfy my curiosity first. I won’t be late, my lovelies.’ As he walks, he imagines what the person he’s searching for might look like. It’ll be someone gentle with delicate features and we’ll become friends, he whispers to himself. He arrives, limping as usual, at the pigeon corner and notices that there’s no wheat on the ground. He’s elated. In a few minutes, he will finally meet his new friend. He decides to wait in the doorway of a nearby shop and sits down, but it isn’t nearly as easy as he’d expected. The pain in his foot causes him to shut his eyes before he can settle into his new position. He takes an old radio out of his jacket pocket, presses the button, and extends the antenna. Fairouz begins to sing: I asked you, my love, where are you going to? A quarter of an hour passes and still no one has come. He stands up and looks into the distance, first to his right and then to his left. Perhaps he’ll see the pigeon’s friend coming. But he doesn’t see anyone interesting-looking, which is how he imagined the person would appear. He sits back down in the doorway. A grey pigeon lands on the ground in front of him and searches for any grain leftover from the day before. When it fails to find any, it returns to its companions who are all perched on the heads and backs of the lions in Al-Manara Square. Their little eyes are fixed on their corner of the road, waiting for their friend to come and scatter wheat for them. He examines the empty streets, which remind him of the First and Second Intifadas. These streets were full of rocks and planks and the remains of burnt tyres back then. He remembers the days and nights he’d spent fighting to keep the Israeli Army Jeeps from entering the city. He thinks about everything he did for me, the city he loves. How he defended me as a resistance fighter and how a bullet in his upper thigh had caused the limp he has now, how he refused to leave me to go work in the Gulf, and how these days he wakes up earlier than most of his neighbours in order to get me ready to meet them like a son changing places with his mother.

He stands up, his eyes misty, and turns to walk back toward the area where he works. Before he’s even taken two steps, he hears a voice calling him. ‘Hello there!’ It’s a voice he knows perfectly well, but he doesn’t turn around and he doesn’t return the greeting. He carries on walking, confident that the pigeons will be fed and pleased to have discovered their friend’s identity. Only when he arrives at his own patch does he say to himself, ‘Cities have to know how to keep secrets, don’t they, Ramallah?’

‘Yes, my son.’

Ahmad Jaber holds a Master’s degree in Civil Engineering and is a winner of the Abdul Qattan Foundation Award for Young Writer 2017 for his story collection ‘Mr. Azraq in the Cinema’. He has published stories in many local websites and newspapers.

Adam Talib is an award-winning translator of Arabic literature. He has translated four novels, including Fadi Azzam’s ‘Sarmada’, Khairy Shalaby’s ‘The Hashish Waiter’, Mekkawi Said’s ‘Cairo Swan Song’, and Raja Alem’s ‘The Dove’s Necklace’, which he and Katharine Halls translated together. Other translations for Comma include Ahmed al-Malik’s ‘The Tank’ in ‘The Book of Khartoum’ (2015), Abdallah Tayeh’s ‘Two Men’ in ‘The Book of Gaza’ (2014), and Khaled Kaki’s ‘Operation Daniel’ in ‘Iraq + 100’ (2016). He teaches Arabic and comparative literature at Durham University.

‘The Book of Ramallah’ is out now and available to order here: https://commapress.co.uk/books/the-book-of-ramallah. The anthology is the latest instalment in Comma’s Reading the City series.

Comments