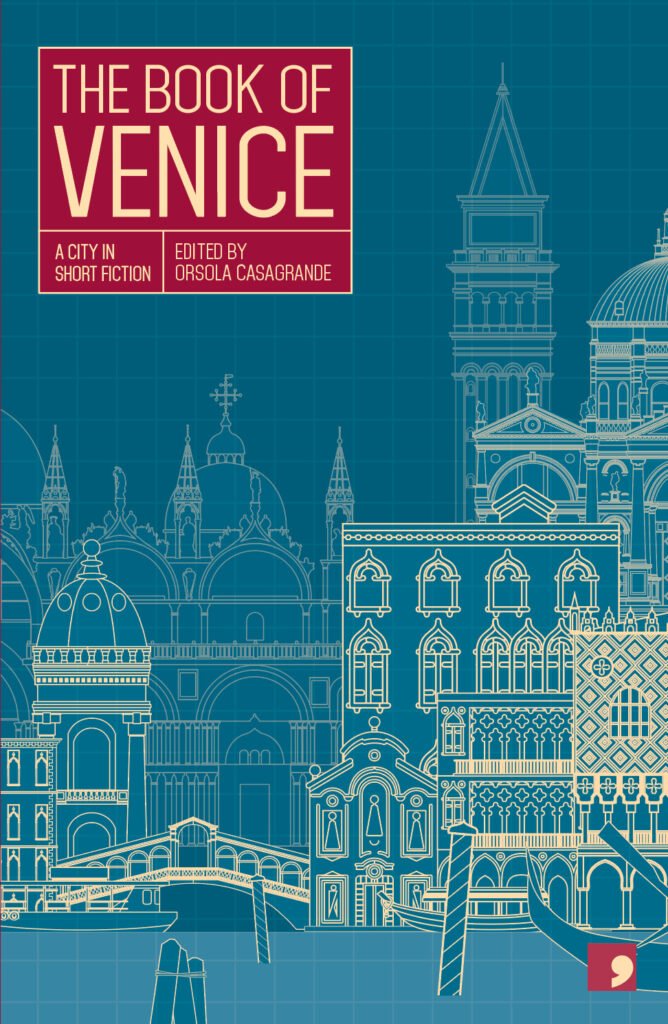

On 27th May, a new addition to our ‘Reading in the City’ series is coming out. ‘The Book of Venice’, edited by Orsola Casagrande, features ten stories by emerging and established Italian writers. This collection explores the double-edged relationship between Venice’s citizens and its visitors, investigating problems of over-tourism and rethinking the renowned city’s future. Rather than a city in stasis, we see it at a crossroads, fighting to regain its radical, working-class soul, regretting the policies that have seen it turn slowly into a theme park, and taking the pandemic as an opportunity to rethink what kind of city it wants to be. We have asked some of the contributing authors to share what Venice means to them and what moved them to write these stories. If you want to hear more about ‘The Book of Venice’, join us for the online launch event on the 5th May. At Italy’s ‘aperitivo’ hour, we will welcome Orsola Casagrande and three contributing authors for readings and discussions.

Orsola Casagrande

Writing about Venice is always tricky. There are some clichés which are hard to defeat. Readers somehow expect to find them, and writers often give in to this desire. This is a city that has been frozen in time, her beauty crystalized and therefore perfect (or at least this is what most people think). When Comma asked me to edit this book, I, being from Venice myself, had my doubts. But then I remembered Henry James writing that “there is nothing new to be said” about this city, and yet I had been reading so many interesting novels and stories in the past two decades proving the contrary. Many were books written by authors you will find in this collection, and they all proved that there is still a lot to say about Venice. The stories in this book will present a different Venice, with citizens struggling to reclaim their city and to preserve her beauty and historical value without accepting the theme park many would like to convert her into. The coronavirus pandemic has suddenly emptied the streets and squares, restoring a balance that was believed to be lost and giving those living in the city time to think about what future they want for her.

Enrico Palandri

My favourite quote about Venice comes from Krishna Kumar, a Buddhist monk who wrote in the 1500s: “I know that beyond the plains and the seas there is a city, anchored in the water, suspended between sky and earth, which is made of light and colour and it is called Venice. It is there I would like to be taken in a dream, where silence lives, where contemplation and beauty yield happiness.” I hope Kumar would not be disappointed if he had really been to Venice. Like for this monk, dream, silence, contemplation, and beauty are already here for most of those who engage with this place. They are narratives that keep developing from an amazingly beautiful story. Politically and culturally, for those who care to understand it or are curious about it, Venice is truly rewarding and never stops giving. Greeks and Romans, Slaves and Armenians, Christians, Jews and Protestants have lived here together for 1600 years, and their stories emerge through poets such as Shakespeare and Goldoni, painters like Titian and Canaletto, musicians like Vivaldi. This is why I love it so much, because there are so many layers and metaphors in this city that you constantly encounter its narratives, and they are never-ending.

Samantha Lenarda

Venice is one of those cities you fall madly in love with. It is uncomfortable, tiring and gives you no break. Everything in this city means difficulties that do not exist in other cities.

An example: when shopping you need to have a shopping trolley in which to put your food and take it home, crossing bridges in all kinds of weather: it is definitely an enterprise. Everything leads to a different way of approaching things because the communication and transport route is water and what in other cities moves on land, in Venice travels by boat or on foot. Imagine the garbage collection, the post office, public transport, everything has another dimension, another form. Everything undergoes a sort of forced slowdown. Thus, the relationship between Venice and its citizens has another rhythm. It is the city of the future, the one that everyone is looking for, that “human-friendly” city that follows the speed marked by paces and heartbeat. Or rather, it would be nice if it really were such a city. Venezia 2084 is a crude, merciless story about the lack of foresight of a political administration that, in recent decades, has shifted all attention towards an economy geared exclusively to tourism, shifting the needs of the citizens to the background. In this story, the citizens had to find their place elsewhere.

Ginevra Lamberti

A couple of years before the pandemic, I was working seven days a week in the vast field of Venice tourism and, at the same time, dealing with a grieving process. A family member had just died, and I started reading about death education and body disposal options. I was also dealing with the failure of a dream. Back in 2005 – when I first moved to the floating city – I thought it might be my home forever. After 15 years, I found myself struggling not to be kicked out of it because I wasn’t wealthy enough. Suddenly there it was: the idea of a novel about loss, death, graveyards, thanatology and everyday life set in the most idealized city in the world.

The novel ‘Why I begin at the end’, from which the excerpt contained in ‘The Book of Venice’ comes, was published in Italy at the end of 2019. Here I narrate a Venice both loved and hated, protective and pretentious, generous and awfully greedy. A city where everyone fights against everyone else to own at least a scrap of it. An almost-organic creature filled with complexity.

Michele Catozzi

As I was born in Mestre, in the mainland of Venice, I frequently paid a visit to the City and was always torn between continental native pride and envy for Venetian islanders, the real locals. That’s probably why my novels, a series of Police Procedural stories starring Inspector Aldani, are set in contemporary Venice. Aldani was a kind of personal revenge against the fate that had me born on the mainland and not on the “laguna”.

When I was asked to write a short story for ‘The Book of Venice’, I was very excited, and I thought it would be an easy ride. Not at all. I did not consider the incumbent presence of the City, with all its globalised stereotypes and problems, from over-tourism to “acqua alta” (high tide), from depopulation to the lack of residential housing.

Every story I imagined rapidly filled me with all this kind of “deja vu” stuff. That was not what I wanted to write about. So, after the deadline had already passed, the solution flashed in my mind: I would write a crime story without a crime… A story starring the same characters of my novels, above all, my Inspector Aldani. The starting point was very simple: the news about the move of police headquarters in Venice to the mainland.

The move is highly representative of the difficult relation of the City with the mainland. It symbolised the dispossession of its normal life landmarks and their moving to the mainland, leaving Venice free to evolve to an amusement theme park for tourists: “Veniceland”. By the way, the news of the police headquarters move is completely true…

If you want to hear more about ‘The Book of Venice’, join us for the online launch event on the 5th May. At Italy’s ‘aperitivo’ hour, we will welcome Orsola Casagrande and three contributing authors for readings and discussions.

Pre-order the book here.

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: book, book of Venice, city, Comma Press, publish, publisher, Venice

Comments