On Andrea Dunbar, the playwright who showed “Thatcher’s Britain with its knickers down”

December 24, 2020

Source: Bradford Lit Fest

The 20th of December 2020 marks 30 years since the death of Bradford-born playwright Andrea Dunbar. Dunbar’s most famous work is undoubtedly her 1981 play ‘Rita, Sue and Bob Too’, which was later adapted into a film of the same name by British director Alan Clarke. Although the film achieved widespread success on its release, Dunbar’s name is rarely mentioned in the line-up of great British working-class writers. Her writing falls outside the time frame of 1960’s ‘kitchen sink’ realism where it would perhaps have found its perfect home. Her themes, however, not only seem prevalent to this time, but still ring true today. Using experiences from her everyday life, Dunbar perfectly encapsulated the bleak situation faced by those on the lowest rungs of British society.

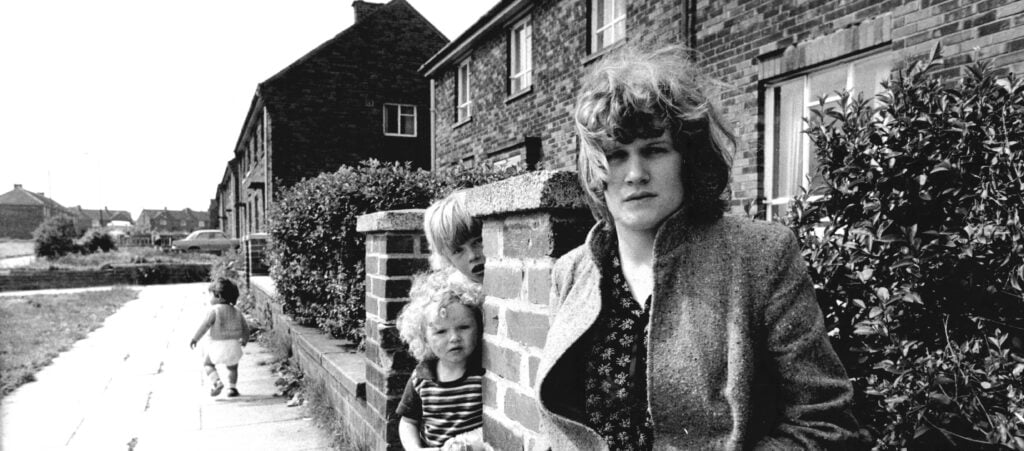

Dunbar was brought up on Bradford’s Buttershaw council estate. Her surroundings growing up poignantly demonstrate the 1980s government’s irresponsible handling of its most vulnerable. It is therefore unsurprising that her semi-autobiographical plays encompass a life surrounded by violence, alcoholism, underage pregnancy and poverty. Dunbar approaches these themes directly in her work, refusing to flinch away from portraying the harshness with which families in her world are willing to attack each other verbally, and threaten each other physically. Her first play ‘The Arbor’ was written when Dunbar was only 15; scrawled in green biro on a page ripped from a school textbook, the play would go on to win her the accolade of youngest writer ever to have a play produced at the Royal Court Theatre.

The release of the film version of ‘Rita, Sue and Bob Too’ caused backlash for Dunbar on the Buttershaw estate. Although it has been reported that many of the occupants were outraged, Dunbar claimed in a BBC interview that only around three people complained to her, which “is not bad off a whole estate is it?”

Dunbar would spend the rest of her life on the Buttershaw estate where she would have three children: Lorraine, Lisa and Andrew. Her writing would be sporadic, with alcoholism and family issues notably dominating her time. Dunbar eventually died at the tragically young age of 29, suffering a sudden brain haemorrhage in the Beacon pub. The same pub which centers in the opening shot of the 1987 film version of ’Rita, Sue and Bob Too’.

This film version of Dunbar’s play does what it says on the tagline, showing “Thatcher’s Britain with its knickers down”. Not only do we see the sexual side of 1980s Conservative England, but we also see the private aspects of people’s lives whose tragic situation has turned them against each other. The tagline also, however, encapsulates the issues that a modern viewing of the film bring to light. The storyline of two teenage girls engaging in sexual activity with an adult man now reads as an awful tragedy on grooming and sexual abuse, not, as the film would portray it, as a lighthearted sex comedy. The film’s treatment of the material now seems not only insensitive, but actively damaging.

This perhaps in part explains why the film is rarely listed amongst those of a similar kind by directors such as Ken Loach or Mike Leigh, whose work is heralded as showing the bleak realities of working-class England. ‘Rita, Sue and Bob Too’ shows its age. In doing so, however, we perhaps have an even more shocking example of realism. Watched as a piece of history, the film shows the abhorrent societal attitudes towards the issues that surround its narrative. When read as words on a page today, Dunbar’s comic brilliance still shines through and what we also see, however, is a harrowing insight into her world.

Many writers have handled the topic of the world from which Dunbar comes, but few have also experienced it first hand. Her unfortunate situation offered her an insight into a world which few could grasp a true understanding of. Theatre director Max Stafford-Clark referred to Dunbar’s work as “an articulate record of life in the lower depths recorded not, for once, by an outsider but by someone still passionately involved in that life themselves.”. Her work gives a key insight into this world, opening up conversation about those who were left behind by a political sphere obsessed with upwards mobility. When asked about her work in a BBC interview, Dunbar noted that she didn’t find it shocking to write about what happened on the estate, it was simply her normality. Her realism was not something artificially constructed, but something she lived through and documented.

Dunbar’s story has been explored by multiple artists. Two works of note are Clio Bardnard’s film ‘The Arbor’, and writer Adelle Stripe’s book ‘Black Teeth and Brilliant Smile’, which gives a dramatised account of Dunbar’s life. Both portray a life plagued with issues, but one which brought invaluable insights into a world which is often demonised, little documented, and even less understood. Dunbar’s work not only acts as gripping realist drama, but embodies issues often only viewed from an outside perspective.

BBC Inside Out feature on Andrea Dunbar is available here.

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: 80s, Andrea Dunbar, author, kitchen sink realism, play, Playwright, realism, Rita Sue and Bob Too, Thatcher, The Arbor, working class, writing

Comments