‘Performance is where I can be sick in the way I want’: Martin O’Brien @ DaDaFest

December 20, 2018

In the carpeted comfort of the Reid Room in Liverpool’s iconic St George’s Hall, Martin O’Brien is presenting a performance lecture. ‘Until the Last Breath is Breathed’, named for the video installation premiered in the heritage centre below. O’Brien stands at a lectern, naked but for a pair of cut away, white y-fronts. His face is bathed in the warm yellow light cast from an upturned green bankers lamp. An eerie shadow plays on the wall behind him.

He begins by narrating the scene played out on the video projection on the wall behind him. In a darkened space, he sits in front of a candle. He blows it out and immediately it relights itself. He repeats until it is completely extinguished. “We were in complete darkness. Now everything is different. Time is different, this is the beginning of the zombie years.”

What follows is a performance lecture which explores Martin O’Brien’s concept of the “zombie years”: the years which lead up to the expected end of his life. O’Brien is a live artist known for durational solo performances concerned with physical endurance, hardship, pain and excess. He was born with cystic fibrosis, a condition which creates a build-up of thick sticky mucus in the lungs, digestive system and other organs, the long-term effects can cause difficulty in breathing and recurrent infections. The life expectancy of someone with cystic fibrosis is 30.

As a result, O’Brien’s art practice is informed by the lived experience of his condition. The texts he presents tear across a narrative terrain that is at times autobiographical, fantastical, surreal and apocalyptic. His anecdotal ramblings are heavily informed by Catholicism, queer culture, illness and the notion of the zombie apocalypse – and we are swept along for the ride. Inspiring uneasy laughter, he describes an apocalyptic zombie rampage with another “queer zombie”. The audience is lured into the description of an idyllic country landscape with a river running through it before it mutates into a river of mucus, thick and slow moving, green and sticky. A river of disease that affects everyone surrounding it. Lurching between humour, discomfort and the grotesque, O’Brien’s takes us on a visceral tour of his experience of illness and his way of dealing with it.

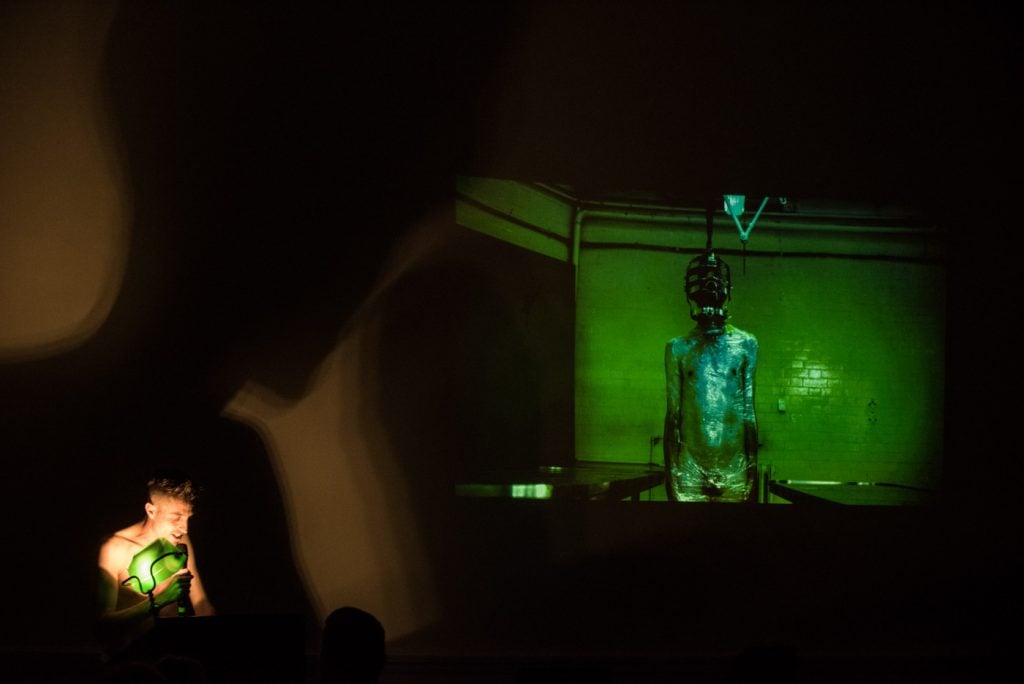

In the former cells in the basement of St George’s Hall, O’Brien’s three channel video installation is a durational piece filmed in an old abandoned morgue in south east London in the 30 hours leading up to his 30th birthday. He films an action on the hour, every hour, sometimes on his own, sometimes in collaboration with artist friends. These actions are, at times, uncomfortable to watch.

Lying on a stainless-steel gurney, he beats his chest with his fists until it is red raw and he begins to cough, hacking up a glob of mucus which he places in a specimen jar. When he has filled enough jars, he kneels on the gurney, looks at the camera and begins to use the sticky threads of mucus to style his hair.

In another instance, he places a rubber hood over his head. He slowly pulls in deep, rasping breaths making the hood cling to his face. He drops to his knees and slowly crawls around the base of the gurney. The tension becomes almost unbearable as his breathing sounds more desperate. Eventually, he comes to his feet, finally pulling off the hood.

O’Brien’s practice appropriates the sick body. Subverting his potentially passive, submissive and vulnerable state, in performance he has agency over his body and creates space to utilise medical procedures and aestheticise medicine. He says that “performance is the place where I can be sick in the way I want to be sick, or I can use medicine in the way I want to use it. I have total control over that space.”

‘Until the Last Breath is Breathed’ is a significant piece of work in many ways. It operates as a retrospective of an artist whose practice, until now, has been overshadowed by the presence of death and through performance has appropriated a condition which should have ended his life early. It’s a visualisation of O’Brien’s personal path of coming to terms with the situation and consequently a reflection on his identity as an artist.

Having worked on the piece for over a year, O’Brien found the most appropriate context to show it was this year’s DaDaFest International. The theme of the festival (‘Passing: what is your legacy’) clearly resonated with the work. DaDaFest platforms the work of deaf and disabled artists and aims to present the lived experience of disability. O’Brien’s work does exactly this in a way that challenges the viewer, demanding us to confront the visceral reality of sickness, pain and death. He talks about the significance of politics and the taboo within his practice: “I think with illness and death, it’s hard to talk about it, and it seems to me completely pointless to try and make it clean and pretty. So to actually bring or allow a dirtier or kind of difficult practice of work is really important.”

‘Until the Last Breath is Breathed’ is the artist’s rite of passage which marks the transition from one self to another. From the artist moving towards death to the artist “having death inside him”. Carrying this experience, O’Brien is currently planning a new commission which can take place over the next five years and being in the early stages, he does not yet know where the work will take him. With such a profound understanding of the fragility of the body and the passing of time it will be fascinating to watch how his future work takes shape in the zombie years.

You can have a look at Martin O’Brien’s DaDaFest profile here

Filed under: Theatre & Dance

Tagged with: body, cystic fibrosis, DaDaFest, Disability, lecture, Martin O'Brien, performance, physical, sickness, St George's Hall, visual art

Comments