“I’ll find friends to wear my bleeding roses” – Somerset, Henry VI part 1 (2.4.73)

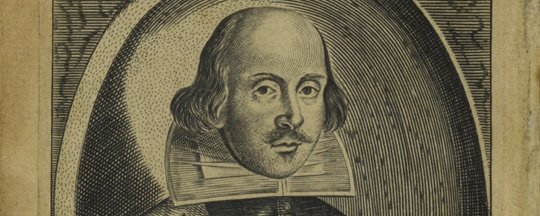

2016 marks the four hundredth anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 1616. To celebrate this milestone and honour the bard of Avon’s work, the University of Leeds’ Treasures of the Brotherton Gallery plays host to a special exhibition featuring some of the world’s rarest printed Shakespearean texts and paraphernalia.

This exhibition is a must-see for any Shakespeare enthusiast who has an affinity for Yorkshire history; to qualify, that of course includes anyone who speaks the English language and has any real taste. The exhibit explores Shakespeare and the idea of regional identity, which is reinforced by a huge medieval map of Yorkshire festooning an entire wall. Rather than being an amalgamated merging of both Shakespeare and the history of Yorkshire, the display wisely chooses to parallel the incredible Brotherton collection of Shakespearean texts and contemporary works with a digital exploration of the history that links England’s national poet with God’s own county.

Considerable chunks of both Henry VI (part 3) and Richard III are set in Yorkshire, and the arrangers at the Brotherton Gallery have picked up on this, choosing to display a fabulously ornate fourth folio (a collection of Shakespeare’s works dated 1685) open on the title page of the eponymous Richard; one of Shakespeare’s most heinous villains, who was the last Yorkist king and incidentally the last English monarch to die in battle. This is displayed alongside Edward Hall’s ‘The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of Lancaster and York’ (1548) a key chronicle that is said to have been Shakespeare’s main inspiration for his War of the Roses history plays; Richard II, all three parts of Henry VI and Richard III.

The exhibition also shows off some other fantastic tomes. A luxuriously bound version of the second folio (1632) is possibly the rarest and definitely the highlight of the Shakespearean literature on display. Other later works include; Ben Jonson’s 1616 Collected Works which set the precedence for the posthumous collating of Shakespeare’s work and Beaumont and Fletcher’s 1679 collection of ’50 comedies and tragedies’.

Astutely, the gallery also displays a number of Brotherton’s re-worked Shakespearean texts. Including Nahum Tate’s famous re-working of King Lear (1681), Dryden and Davenant’s musical version of ‘The Tempest’ (1735) and Garrick’s “Romeo & Juliet” (1766). Shakespearean scholars will appreciate this as a nod to the integral nature of editing to the Shakespearean process. By this I mean that Shakespeare’s works themselves were hardly ever original material, and that the precedent in Elizabethan times was to re-work existing texts, something which the bard of course excelled at.

This dynamic editing process continued long after the bard’s death. Most famous is Nahum Tate’s re-working of King Lear. Lear, one of Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies, was considered too bleak for restoration stages and subsequently had its infamous ending completely re-written. The ‘original’ version of Lear didn’t return to stages until 1838, and it probably wasn’t until the nihilism of the 20th century with the threat of nuclear annihilation looming large that Shakespeare’s version found the popularity it deserves.

There is even a collection of Shakespeare’s sonnets (1640), bound in red leather and velvet, which are edited into longer versions and given titles. The traditional Petrarchan (Shakespeare’s form was a slight variation of this) sonnet, at its height of popularity in the 1590’s, had fallen out of fashion by the mid 1600’s. Such open editing, almost plagiarising, further emphasises the integral nature of the editing process to the success and endurance of Shakespeare’s work.

The Brotherton gallery chooses to explore this rich blending of history and fiction through the use of digital interfaces, which one can peruse and interact with alongside viewing the exhibits. These ipad-like interfaces illustrate not only how Shakespeare used history as a mirror for his present, but also how his plays could be powerful political weapons. This is highlighted by a disclaimer on Henry IV part 2, separating the perceived likeness of the jovial Oldcastle (later changed to Falstaff) with the real-historical John Oldcastle.

Finally, the exhibition chooses to link the regional history of Yorkshire and the Bard of Avon’s work by displaying the apocryphal ‘Yorkshire Tragedie’, a work by Thomas Middleton about murder in god’s own county that was wrongly attributed to Shakespeare. This is accompanied by the more recent ‘Shakespeare’s War of the Roses’ (2006), a Northern Broadsides production directed by Barrie Rutter that blends Henry IV parts I,II and III with Richard III, a version which roundly sums up the entire exhibition.

Pleasingly, the exhibition accurately recognises the fallacy of the idea of a definitive Shakespeare. The linking of Shakespeare and Yorkshire is a clever, if slightly tenuous, way of displaying this incredible collection in a way that draws in those who perhaps are less interested in Shakespeare as they are Yorkshire history. The good people at the Brotherton Gallery have done a terrific job of modernising what is essentially a text heavy display by including digital interfaces and wall projections. The be all and end all* is that this exhibition is a must-see for any worshipper of Shakespeare and any lover of Yorkshire history, and it is thanks to galleries such as the Brotherton that the legacy of the bard’s work really will last forever and a day**.

*Macbeth

**As You Like It.

For more information please visit the Leeds University Library website.

Filed under: Art & Photography, Theatre & Dance, Written & Spoken Word

Comments