The cumulative weight of the numerous reports describing this dire position should alarm anyone committed to equality, but if the sector insists on categorising class as a ‘tricky’ issue, any sustained change will continue to be avoided.

It feels like only yesterday that Maxine Peake gave her keynote interview at the British Film Institute in 2018 during the launch of the paper ‘Panic! Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries’ from Arts Emergency and Create London. Peake shared her experience of the prejudice she encountered as a working-class woman, at one point being asked to adopt a more class appropriate accent to play a barrister. It’s been two years since then, so has anything changed? Do British TV producers still think it’s implausible that someone with a Bolton accent could pass the bar examination? According to two reports published this year ‘Getting in and getting on: Class, participation and job quality in the UK’s Creative Industries’ from the Policy and Evidence Centre and ‘Cultured Communities: The crisis in local funding for arts and culture’ from the Fabian Society, nothing much has changed at all. Despite a steady stream of papers and reports decrying the systemic underrepresentation of diverse working-class and other marginalised communities in the arts and culture sector, this dismal situation has effectively been preserved in aspic since at least 2014.

So what’s with the inaction? Well, wider society still views the working-class as beneficiaries of creative output but not necessarily the curators, originators or producers of it. I learnt this early on in an encounter with a careers advisor. My Mum delights in telling people that I dreamt of being an archaeology curator from an early age. Liverpool Museum (now World Museum Liverpool) had certainly cast a spell on me, as had watching repeated television screenings of Harry Hamlin as Perseus in ‘Clash of the Titans’ (1981). By 15 I had my sights firmly set on becoming an archaeologist but the careers advisor wasn’t too convinced. He politely asked me to choose something seemingly more attainable for a working-class teenager: I opted for marketing because I had a thing for graphic art and had taken part in Young Enterprise. You’ve probably guessed by now that I wasn’t snapped up by Saatchi and Saatchi. Instead I ended up in a ditch digging up Roman roof tiles in southern Italy for a University of Edinburgh archaeology degree.

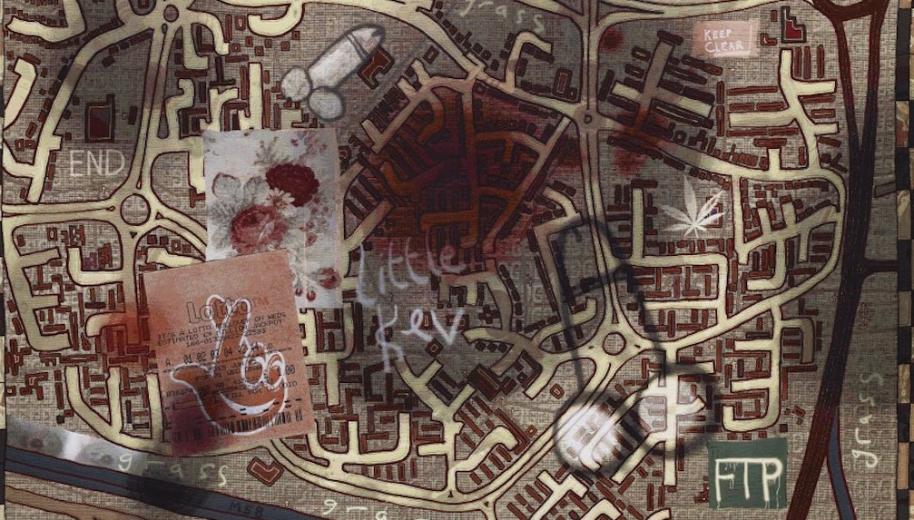

I don’t think any of those roof tiles ended up in a museum but contrary to my careers advice I eventually did. For 15 years I was a curator at both the International Slavery Museum and Manchester Museum, with a stint as a visitor services assistant at Urbis (now the National Football Museum) and temping at a café, call centre and housing association in between contracts. So you can imagine how excited I was when working-class artist Grayson Perry paid a visit to Skelmersdale, my home town, back in 2015 to shoot an episode of his Channel 4 series on masculinity ‘Grayson Perry: All Man’. The theme resonated with me because as a queer kid growing up in Skelmersdale my manliness or otherwise was a source of fascination and frustration to fellow classmates. The episode stoked the ire of locals for repeating pessimistic clichés about the town but Grayson was undoubtedly sincere in his aim to understand the abandonment felt by working-class men. Their lives inspired Perry to create two artworks, ‘King of Nowhere’ (2015) and ‘The Digmoor Tapestry’ (2016).

Grayson Perry, The Digmoor Tapestry, 2016. Source

The artworks didn’t remain in the town for long, instead they embarked on a tour of art galleries in more well-off areas, including the Serpentine Gallery in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London. Here audiences from privileged backgrounds could expose themselves to working-class angst from the comfort of an exclusive postcode. It’s unsurprising they didn’t stay in Skelmersdale, firstly because there’s no art gallery and secondly because working-class access to art and culture is often seen as a luxury not a necessity. Art critic Brian Sewell exemplified this attitude claiming audiences in the capital were more sophisticated than their northern counterparts back in 2003. His indignation was driven by the opening of ‘Cobra’, a touring exhibition of radical post-war artists and poets at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead, and not a London venue. Sewell, who passed away in 2015 aged 84, courted controversy but to dismiss his elitist views as an aberration or anachronistic would be remiss.

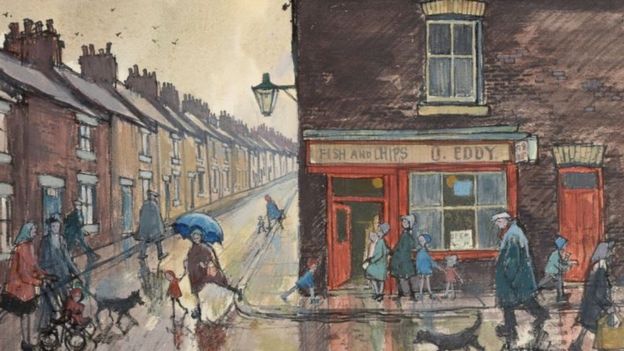

Only several miles north of the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, working-class historian David Olusoga was raised in a council house during the 1980s. The idea that a council estate in a post-industrial town like Gateshead could produce an academic, broadcaster, filmmaker and writer of such esteem would have probably been inconceivable to Sewell and his peers. Equally as improbable would’ve been the idea that working-class art made in the region was of any repute. Just over 20 miles from where Olusoga grew up is Spennymoor, home town of miner and artist Norman Cornish. Cornish became a professional artist aged 47 in 1966 and documented life in County Durham. He was spurned by the art world but remained popular in the north east. He posthumously received critical acclaim and two centenary exhibitions of his work in 2019, ‘Norman Cornish: The Definitive Collection’ at the Bowes Museum and ‘Norman Cornish: The Sketchbooks’ at Palace Green Library, were extended due to popular demand.

Credit: Norman Cornish

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not looking to cancel careers advisors or art critics. My point is this: classist attitudes and behaviours are deeply ingrained in the arts and culture sector, and without a seismic attitudinal shift to address this, working-class inclusion and opportunities will remain at microscopic levels. The cumulative weight of the numerous reports describing this dire position should alarm anyone committed to equality, but if the sector insists on categorising class as a ‘tricky’ issue, any sustained change will continue to be avoided. That being said, diverse working-class young people aren’t simply waiting around for things to change but are taking action now. Organisations like Arts Emergency and Reclaim are working with these youngsters to ensure that they have the confidence, resources and support necessary to realise their ambitions, including becoming a museum curator should they so wish. For those of us from working-class backgrounds that have managed to get our foot in the door, we need to do much more than simply prop it open. We need to act in solidarity with other marginalised communities and, to quote Michael Caine’s character Charlie Croker in the film ‘The Italian Job’ (1969), metaphorically “blow the bloody doors off!”.

Filed under: Community

Tagged with: accent, art, attitiude, class, classist, Culture, curator, David Olusoga, diverse, Grayson Perry, inequality, marginalised, Maxine Peake, museum, Norman Cornish, opportinity, sector, solidarity, support, working class, young people, Youth

Comments