The photographs in Martin Parr’s book, Small Worlds (1995) are of tourists. They are photos of people taking photos, of souvenirs with photos printed on them, of people wearing t-shirts with the photo of the attraction they stand in front of printed on it. The photos display people and places and things transforming into images of themselves. Martin Parr manages to poke fun without being malicious. He makes apparent with his photographs the way in which two very characteristically modern activities, photography and tourism, have grown in tandem. Susan Sontag, points out that most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever it is that they meet. Photographs both certify experience and limit it, by converting the experience into an image, a souvenir. Martin Parr’s photographs, showing tourists mimicking and mirroring the forms of the object of their visit, for me so perfectly illustrate the funny way in which we experience the world around us. The way in which tourists photograph what they see not to discover something but instead to confirm that the way in which they see the world is right and true.

With this collection of photographs in mind I was excited to hear about an exhibition, currently on show at Manchester Art Gallery, curated by Parr, of photographs taken of Britain, by photographers from elsewhere. The work of 23 photographers, from Europe, Japan, North America, depicting British life as it has been lived over the past 80 years.

A large proportion of the show is taken up with the kind of photographs you would expect to see portraying Britain. Bruce Davidson and Evelyn Hofer capture the habits and tastes of British people, their photos containing formal dress codes, seaside rituals and whimsy. Frank Habicht, Gian Butturini and Candida Hofer show us the swinging sixties. Viewing these photos today they are steeped in nostalgia. It is a nostalgic time right now, and photographs actively promote nostalgia. It is almost as unusual to pass a day without seeing a photograph as it is to miss seeing writing. As well as seeing photos on our mantlepieces, in advertising and television, we now have Facebook, Instagram and Pinterest permeating our environment with photographs. Photographs of the past constantly bombard us making us nostalgic for times we weren’t even a part of; and with all the filters available to us, we can make it appear like we were in fact a part of them. With all this imagery available to me every day, pictures featuring bowler hats, tea-drinkers, doorstep milk, double- deckers buses and other cliches of British culture are slightly lost on me.

Parr writes in the catalogue, “cliches have not become cliches without good reason”. He claims these portraits of Britain to express a truth about the place that a homegrown photographer may have deliberately avoided, or forgotten through over-familiarity. This may be the case, however for an audience I don’t think these photos surprise or amuse in the way that Parr’s own photos do.

Where this exhibition does succeed is in its transparency. Each photographer is introduced, the motives for their photo-taking explained and an idea of where they are coming from given. For example we learn that Bruce Davidson was commissioned by a British magazine called The Queen in order to ‘portray an outsider portrait of England in 1960’, that Cas Oorthuys was a photographer for a Dutch social-democratic workers press and the photos by Garry Winogrand, were taken after he’d already had his own show at MOMA, and therefore was a very well established artist photographer. With this information given to us about the photographers whose work we view, we can make our own minds up about the Britain that is presented by them and consider how their political and artistic backgrounds will be influencing their work.

Photography so often stands for ‘truthful representation’ over other art forms. However the camera is never neutral. Just as a painter creates an artwork so does a photographer create their image. In deciding how a picture should look, in preferring one exposure to another, photographers are always imposing standards on their subjects. We might see a photo of a sad looking child and let that photograph speak for not only that child but also the place and time in which it is captured. But we have no idea of how many shots the photographer took before they came to that image. They may not have merely captured that image while passing by but have photographed over and over again until the precise expression on the subject’s face supported their own notions about poverty, dignity, or whatever it may be, in that location they photograph.

While photographs appear to speak for themselves, art historian, Abigail Solomon-Godeau urges us to ask the question ‘Who is Speaking Thus?’. She insists we examine the photograph as:

• ‘spoken’ within language and culture

• ‘speaking’ of agenda both personal and institutional

• ‘spoken’ in a particular historical frame

In giving us information about the photographers and the conditions in which they took their photographs, Parr enables us to consider these questions in contemplating the works on show.

In a series of photographs taken of Glasgow by the French photographer, Raymond Depardon in 1980 an understanding of the background of the works is particularly important. These photographs of Glasgow’s dreary streets depict what we would expect of Thatcherite Britain with its recession and record unemployment. However when we learn that Depardon was commissioned to document Glasgow for the Sunday Times as ‘part of a series on european cities whose reputation had fallen by the wayside’ it makes us question their validity. Depardon approached the city with an agenda in mind, to photograph an impoverished place a place ‘fallen by the wayside’. Without social change as its purpose these photos were taken for The Sunday Times, a paper in favour of a Thatcher government and most commonly read in southern parts of England and very little in Scotland. These photographs highlight the differences between the then viewer of the photograph (largely tory southerners) and the subject of it (working class Glaswegians) by presenting one as educated and informed about its ‘other’ and one as oblivious and ignorant, both to the photographer and to those viewing the photograph.

This ‘othering’ or exploitative ability of the photographer and its camera, is most apparent in this exhibition in the work of Bruce Gilden. His photographs are of faces, close up, cropped tightly so that no sign of the street is left, the viewer is confronted with every contour and crevice of the face.

Gilden may be attempting to questioning perceived notions of beauty with his photographs of ‘faces were inclined to look away from’, but the exploitative way in which he captures the images overrides this. He catches his subjects on the go, unawares, lost in thought, using a flash to shock them and to capture their surprised faces. His images of the ‘invisible people of Dudley’, an attempt to document working class Britain fall into the trap of what the feminist artist Martha Rosler calls ‘victim’ photography. These subjects are twice victimised – first by society and then by the photographer who presumes the right to speak on their behalf. We do not feel invited to identify with the people photographed but instead to look upon them and feel uncomfortable. The camera has the power to catch so-called normal people in such a way as to make them look abnormal. These subjects are caught looking straight into the camera, shocked by the flash making them look almost deranged, the extreme close-up and high-definition of the images only adding to this.

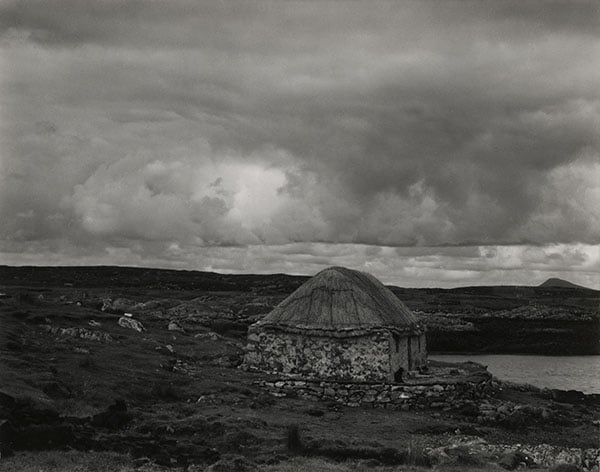

The photographs I really loved in this exhibition, and that provided a refreshing, interesting and unexpected portrait of Britain, that did not fall in to the traps of those previously discussed. were those focused on places and activities over people. Paul Strand’s beautiful images of the Outer Hebrides, of still and brooding buildings and landscapes as heroic in their resistance of the relentless thrust of capitalism.

Axel Hutte’s photographs of London social housing estates, architecture once signalling a progressive and optimistic era, now symbolising anonymity, austerity, alienation. Jim Dow’s colourful portraits of shop fronts. Focussing on corner shops, independent shops, those shops now disappearing rapidly from our streets. These three photographers all focus on capturing declining and disappearing aspects of British culture, they present nostalgic imagery without giving in to cliches. Cameras began duplicating the world at that moment when the human landscape started to undergo a rapid rate of change: these artist make use of the camera as a device, available to record what is disappearing, beautifully.

Shinro Ohtake’s scrap books filled with sweet wrappers and tickets, may seem out of place in a photography exhibition but the art of collecting often goes hand in hand with that of photography (Parr himself is an avid collector of postcards and other souvenirs), and the inclusion of these in the exhibition alongside Ohtake’s photographs of advertising, is a clever way for Parr to draw attention to the photographers included in this exhibitions status as tourists, visitors to Britain, collecting souvenirs to take home with them.

Hans van der Meer’s photos of amateur football matches draw parallels with Dutch landscape painting, the backdrops to the games, mountain views, cloudy grey sky, pointing to the theatre of the game and providing endearing images of a game so ingrained in Britain’s culture. These photographs are such a welcome alternative to the images of football fans so often favoured by photographers to represent the place of football in our culture.

Sergio Larrain’s blurred, black and white photographs are great examples of ways in which a photographer can approach people and places while avoiding stereotypes and the expected. Setting out to photograph the dramatic change of a post-war Britain Larrain uses weird angles to capture movement and the beautiful shapes created by light and objects in the city. Photography often implies that we know about the world if we accept it as the camera records it. However this is the opposite of understanding. Understanding starts from not accepting the world as it looks and that is why Larrain’s surreal images of London, showing us the city in a way we don’t often see it is far more honest and interesting than those photographers delivering us images we expect and already know to be ‘what Britain looks like’.

The Anglo-German photographer Bill Brandt, stated, a photographer needs the “receptiveness of the child who looks at the world for the first time or of the traveller who enters a strange country”. Many of the photographers in this exhibition appear to have achieved this, to have captured unexpected and wonderful images of Britain. These displayed in contrast with those photographs captured by artists with obvious agendas and already decided outcomes makes for an interesting exhibition that is well worth a visit. Martin Parr’s varied choice of photographers and informative labelling leaves the viewer not only with a layered and interesting portrait of Britain but also with an insight into the pitfalls, problems but also the power of photography.

Comments