The Long Read: Agency and ethics in documentary photography – on Don McCullin @ Tate Liverpool

January 13, 2021

The current Don McCullin show at Tate Liverpool raised a lot of questions for me around ethics and agency in the field of documentary photography, a medium which I am not particularly well informed on. I asked my good friend and recent MA Documentary Photography and Photojournalism graduate, Ed Carey to talk through his thoughts on the exhibition with me. For context, we saw the show separately; I only saw it at Tate Liverpool, and he saw it both at Tate Liverpool and pre-COVID at Tate Britain.

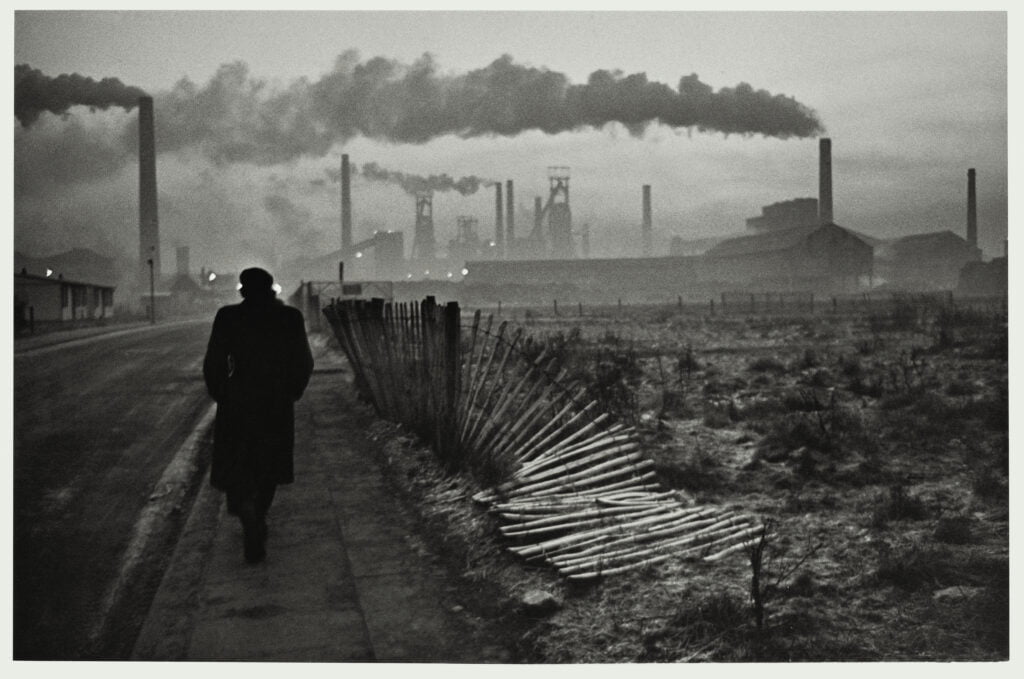

Don McCullin Early shift, West Hartlepool steelworks, County Durham 1963 © Don McCullin

Kezia Davies: When I visited, it was the first weekend Tate Liverpool had opened post-lockdown. I was expecting it to be busy, with that horrible atmosphere of each person shifting from one work to the next. But surprisingly, it was actually completely empty, there was only one other person in there. It was one of the nicest viewing experiences I’ve had in a while. So quiet. I think with the specific work that was on display, it was a better way to view it.

Edward Carey: Definitely. When I saw it at Tate Britain, it was horrible because it just was packed. I knew the images already, I went more to see how it was curated and feel it in the room, but you just couldn’t get a sense of it. Seeing it in Liverpool was much nicer in the sense that it was a lot quieter. I think it felt so much more charged, because there wasn’t that distraction of people talking or other people in the room. There was a much stronger connection to the work.

K.D.: Yeah, the silence gives it more of a sombre atmosphere, which I think is what it needed.

E.C.: Yeah, and it made it a lot more of a challenge to the viewer to approach and to see. The original point of a lot of that work was to shock people, and challenge your sensibilities, and make you realise a world outside of your own. I think in that setting, again, because there’s less of a distraction, you could feel a bit more of the power of it. Especially towards the end, after seeing so many images, I was finding it really hard to look at any of them.

K.D.: Do you think there’s a sense of desensitisation that happens at a certain point?

E.C.: Yeah, it definitely happens. I mean, shock photography is less seen now, because it’s become very clichéd, and people are much more desensitised to it. Charities used to use it a lot, but even they’ve started to change the kinds of images they use, going for images of active work being done, rather than shock photography.

K.D.: I guess in society in general, people are more desensitised; it’s very easy to go online and see those images, so that shock factor kind of dies down. The original aim was to widely disseminate the images to raise awareness and incentivise people to help those in the photographs. But then you put those same images in a gallery, and what happens to that context?

E.C.: It’s really interesting, especially with McCullin’s work, as he said repeatedly “I am not an artist”. But I think, as happens with a lot of photographers and artists, towards the end of their careers their work gets brought back up and viewed in a new light. Photography in the UK has been a lot more popular the last few years so it’s no surprise McCullin’s work has gained popularity in big galleries.

Don McCullin © Tate Liverpool (Roger Sinek)

I think it does become quite murky, but so does a lot in the art world. My take is that the work was made to be widely seen, and the need for it to be seen isn’t gone. If galleries are a way for people to view it, if it’s still having the same, or even any impact, then I can understand it. I also think the distinction is fading between documentary photography and artwork – recently I’ve seen art become much more about message and conversation, and become more politicised, and all of that falls solidly into the framework of documentary photography. So putting it into that setting isn’t jarring for me.

But yes, that idea of putting work in a gallery and claiming yourself not to be an artist – I think it’s just a personal distinction. Considering all he’s done, I could understand how standing in a battlefield taking pictures of people dying and thinking “I’m an artist” would feel very flippant.

K.D.: That makes sense. I guess when he’s taking the photos he’s thinking about how the images created will help the people in them, rather than their artistic potential. But, because the events he was photographing are no longer active crises, the work is essentially historic, right? Do you think that distinct line between documentary photography and art can blur over time?

E.C.: It definitely can, and I think it will always come down to how the images are treated. For instance, in a curatorial sense, what they’re put alongside I think is hugely important. If the pieces are put alongside work with a completely different tone, then it loses its importance. And yes it’s historic, but I think if we ever look at work like that, and think, “oh, well, it was in the past so it doesn’t matter now”, then we don’t learn the lesson that that work is there for. A week after those events happened, the images would have been on people’s breakfast tables, and images like that stay in the social consciousness for a long time because of the impact that they have. You know, there’s the napalm girl from the Vietnam war, there’s Aylan Kurdi from the refugee crisis a few years back. Images like that stick around. I think it always has a space in a gallery because for me art is about opening up dialogue. So, it will always fit.

K.D.: Yeah, and a lot of that is on the curatorial decisions that are made around the work. Obviously this exhibition is a solo show, so it’s given the gravitas that it deserves, but hypothetically, how much would it change the context of the work if it were in a group show?

E.C.: I think it would massively change it. Even if you did a huge group show of all documentary photography work, they would merge together, and something of the work would be lost. Something that Tate Liverpool did really well was having separate spaces for each topic of his work, be it his photographs of the Vietnam war, or of the poverty in Northern England. Giving each of those subjects separate spaces was a really smart way of giving them each the respect that they needed. I think if you then had other work alongside it, it invites comparison, which puts the focus on the artist and the aesthetics rather than the subject of the work. It has to be about the people in those images.

K.D.: That’s very true. I think one point that was really interesting was that, in the opening wall text, it said that McCullin did all of his own printing, which would usually be considered something that an artist does, not something that a documentary photographer does. Obviously, if they were going to be featured in newspapers he’s not printing the newspapers himself, but I’m wondering what happens when you print and frame those images, without the context of the newspaper articles alongside them?

E.C.: So printing your own work would have been much more common in his era, just because it would have been all film work. Yes, he wouldn’t have been printing the newspapers and magazines they originally featured in, but he would have been treating his own film. Printing them up for these kinds of shows does change it but I think maybe the context of the solo show, you could argue, gives it appropriate respect. While those magazines would have been the perfect way to disseminate that work, the images in those magazines would have been alongside adverts and other elements that would lose some of that sense of respect. Having a solo show of just those photographs blown up and framed does heighten it to a certain extent.

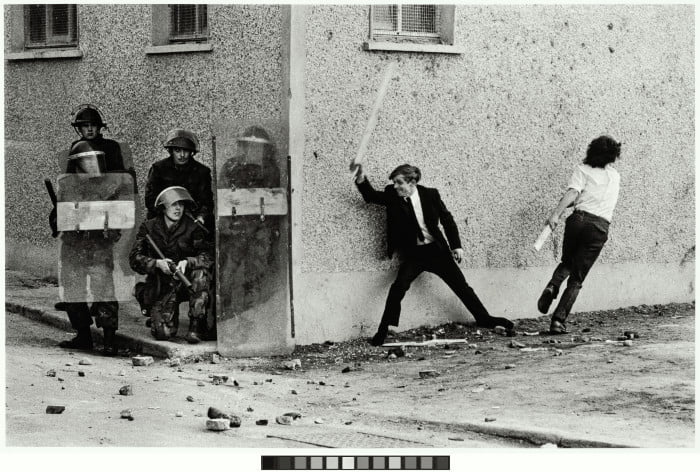

Don McCullin Catholic Youths Attacking British Soldiers in the Bogside of Derry~Londonderry 1971 © Don McCullin

K.D.: It puts the focus on them. Like you mentioned before, each subject had its own section, and each section had its own text panel, but rather than the usual retrospective exhibition texts that would discuss the artist’s life, and the motivation behind the work, it informs us of what was happening in those situations and provides the information and the context that was required to frame the work without centering McCullin. With those text panels, it’s almost like a newspaper that you walk into, in that it frames the images with the relevant context.

E.C.: Yeah completely, and so many newspapers as well, over such a long period of time. While they are historic, they’re not that long ago for some of them. So I think there’s definite worth, and you could say a need to have those images revisited because if the magazines were reprinted and put out again as like, I don’t know, an Anniversary Edition, I don’t know if they would have the same viewership, certainly not the same impact. I mean, the turnout for the London show, obviously pre-COVID, was huge, and it was like that every day that the show was on. So people want to see these photos because they know his name and they want to see them in that context. I think nowadays we are more readily understanding of them in that context than perhaps in magazines.

I had a look at the magazines on display at the show; I think it’s really interesting to read the articles that go alongside them. Images and words go together really well, particularly when you’re looking for context and understanding about a certain situation, an image can only say so much. There’s that adage of “a picture tells a thousand words”, but in reality, you can change the meaning of any image with one word. Having all of the original articles available I think is the only thing that I would add to the exhibition, but it’s the images that people celebrate, and that really tap into this idea of truth and proof.

K.D.: Just going back to the fact you mentioned that the magazines were displayed within the exhibition – I’ve always had this curatorial interest about the distinction between work that goes on the wall and the work that goes in the vitrine, or the display table. It’s always deemed, not necessarily lesser, but supplementary to the artwork. You know, the stuff that’s in the vitrine is not the artwork, there’s a very physical distinction. It’s like wall = artwork, vitrine = not artwork. And it’s really interesting in this context because it’s the exact same image, one in a frame, and one in a magazine.

E.C.: But also the images in the frames are reproductions of the ones in the magazines, the magazines came first, and they’re the reason those images are known. So yeah, I did think having so few, and displayed as they were, was something I would have changed. But also allowing the people in those images the power that they were given by having them framed is important, because agency is always a huge thing in visual art, and particularly with documentary photography. So maybe having the magazines there would have changed it from conversation about the people in the photos and more about “oh look at how these were printed. Isn’t that interesting?”

K.D.: Picking up on that theme of agency, one thing that stood out to me was that none of the people in the images had a voice. In all of those articles, none of them interviewed the people in the photographs, none of them asked their take on what was happening in their own countries. It was a white British man coming over and framing things in his narrative, rather than centering the voices of people living through it.

I think it’s really interesting to think about what happens to the people in the photographs, you know, some of them will still be alive. They’re still alive, and their images are up in the Tate, probably unknown to them. I wonder whether the Tate considered trying to find them and ask for their consent on their photographs being used, because McCullin realistically won’t have got all of them to consent. Even if they did consent to their photo being used in a magazine, they didn’t agree to it being used by Tate, which I think is a really murky area in terms of the ethics of the show.

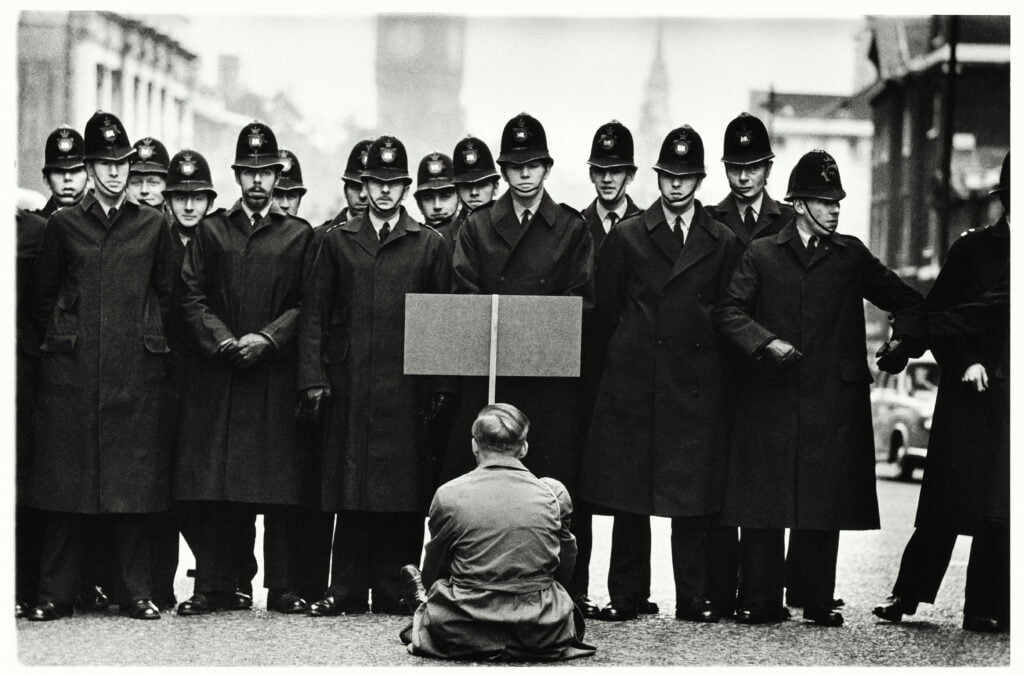

Don McCullin Protester, Cuban Missile Crisis, Whitehall, London 1962 © Don McCullin

E.C.: Definitely. I think a big issue with documentary photography, and any photography really, is agency, because it’s not just artist and audience, it’s artist, audience, and subject. You’re showing people in really vulnerable states, and in really vulnerable situations, and I think McCullin, from what I’ve read about him, and from his interviews, is someone who always approached those situations with empathy and good intentions for the people he took photos of. There are people who won’t have done that, and people who have taken advantage of it.

Documentary photography was born out of a history of colonialism, and was at the foreground of early ethnographic research. It will never escape that, so I think whenever you work with this medium, and especially that subject matter, you have to pay it mind. In those situations, being active in the situation as well, not just walking around the battlefield and taking people’s photos, I think is crucial. With the work itself, these shows now are a sort of a historic view back at these pictures, and, certainly from Tate’s point of view, there’s this really famous photographer, who’s got this incredible back catalogue, people really know him so we know they’ll turn up for the show, let’s get his images and celebrate that. Certainly, when you walk out of a show with that level of impact, your empathy ought to be heightened. But is that enough?

The problem with a lot of artwork, certainly in mainstream galleries, and especially with more political work, is that it’s not active enough. It’s not engaged enough. People can treat the subject with as much kindness as they like, but if the work doesn’t go some way towards solving the problem – not even solving, but at least engaging with the problem – then it’s lacking. It could do better, and all the money spent on it, perhaps could have been used in a different way.

K.D.: I think it very much changes depending on what you’re photographing. For instance, when he was abroad, the likelihood was he couldn’t engage with those people because they didn’t share a common language. But when he was taking photographs in London, and then later on around the North, he really related to the people he was photographing. It says in the wall text these were very similar situations to the one he grew up in, and people even invited him into their houses, like “come and take photos, I want other people to see how I’m living”.

I think that’s different. I think when you’re photographing what’s happening around you, you then have the agency to give that voice, because that’s your lived experience. But when you’re going to another country and photographing someone else in a situation you could never fully comprehend, that becomes problematic. So I think, with your work, for instance, you photograph the context in which you’re living, so you kind of have the agency in that right?

E.C.: Yeah, the difficulty with it is there are so many levels at which the meaning can be completely lost. We’re taught this idea of the three points of viewership; the artist, the audience, and the subject matter. There’s subjectivity at every point of that. I could go somewhere with a solid idea of what I want to shoot, take pictures of people who think they know what the project is, show it to people in a gallery who think they know what the project is, and ultimately, everyone could have a completely different interpretation of what’s going on.

I believe that the work I’ve made about Brexit or my own mental health tells the story that I think it does. But someone from Boston could look at the pictures I took there, and I could definitely see how they could interpret them differently. I went there with an intention, I went there with an idea of “Okay, this is a place to vote entirely opposite myself. How does that come about?”, and I went looking for photographs that might depict that.

Agency and photography, it’s one of those things where it’s really important, because as a photographer, you like to think you are tapped into reality in a slightly different way than a painter or a sculptor. And generally it’s viewed that way by the public, so I think you have to approach it expecting people to interpret it accordingly. So you have to understand the impact that those photographs can have if you get it wrong. That photo can be really damaging if it’s interpreted in the wrong way. As a photographer or an artist, you give a platform to certain things, and what you might intend as a critical political comment might be interpreted as supportive by someone else. And the artist has then legitimised that viewpoint because they’ve put it on the wall. So you have to be very careful.

Especially with McCullin’s work, the idea that the meaning of an image that extreme is so loose, is something to be very conscious of, as both a photographer and a curator. Because our photos are often treated like solid ground. They’re used as evidence in court trials, and they come with the baggage of that. But they’re as shifting as anything else.

Don McCullin Grenade Thrower, Hue, Vietnam 1968 © Don McCullin

K.D.: I think, especially now that anyone can manipulate a photo, and we live in this post-truth era where masses of people don’t trust their governments or even basic science, people have a much more innate sense of distrust than they ever used to. Given the time that a lot of McCullin’s photos were taken, editing photos wasn’t a thing in the way that it is now, people seeing a photograph in a magazine would believe it was the truth. Whereas nowadays, when people see a photograph in a magazine they’re a lot more sceptical.

E.C.: I think they’re a lot more sceptical, but a lot of it is down to the availability of the technology. Everyone who has a smartphone has the ability to take thousands of photos. Even back in the day, if you were lucky enough to own a film camera, you’d have 24 shots that you could take, and the cost of producing those, with the cost of the camera itself, meant that the understanding of how easily swayed an image could be was very different.

We’ve all spent an embarrassing amount of time trying to get the best angle on a selfie, photographers on battlefields are doing the same thing. They’re looking for the right angle or the right moment to take a photo that tells the story they want to tell. So when you look at photographs like those, yes, it’s definitive in a sense, but there are also images either side of that that they’ve chosen not to show you. That choice, you have to remember, is where the subjectivity comes in. This image hasn’t come out of nowhere, it’s come off the back of someone’s opinion and someone’s agenda.

K.D.: And it loops right back to the agency issue. You have to remember that there was a person behind that camera and you have to question what they were trying to do. What was the context of it? How were they framing what was happening? Because it’s just one single image.

E.C.: You can’t walk away from any exhibition like that, or any series of images by a single artist and say “oh, I understand completely that situation” because it comes from a photographer’s viewpoint, it comes from their opinion. Other newspapers or magazines will have sent other photographers who will have had a completely different angle on it.

The day the image of Aylan Kurdi washed up on that beach was published, every newspaper in the UK used it. Looking at how they used it is really interesting. In The Independent, the whole front page was that photo, no text, just ‘The Independent’ over the top. But other newspapers all put different headlines alongside this same photograph. Publishers have agendas, artists have agendas, galleries have agendas. You see that quite plainly just from the fact that it’s one image that they all use, and they all chose to use it in different ways.

K.D.: I remember writing about that photograph when it was published and saying that image had no politics. It’s a child drowned on a beach, it has no agenda, how can it? Unfortunately, I have to look back on that and think how naive it was, because of course it does. It didn’t have as much of an effect on the conversation as I would have liked, but it certainly got David Cameron, and a lot of the press to stop referring to refugees as cockroaches, and a swarm. His speech the next day was a complete U-turn from what he had previously said, saying that we now needed to help with the refugee crisis. I haven’t read every publication, but I’m sure the Daily Mail didn’t have anything too nice to say.*

EC: I think shocking images like that still have worth, and as much as we sometimes forget the subjectivity of them, and how important agency is, if they’re used in the right way, it can sometimes not matter. The image of the girl in Vietnam running from napalm without any clothes is another image that people know. Yes, there’s not a lot of agency in there, that is a child in excruciating pain, whose home has just been destroyed, but it had a huge effect. So sometimes slightly dubious ethics when it comes to taking those photos can ultimately have a positive result. If you go into it with the idea of wanting to change the narrative, and you try to help after you’ve taken the photograph – you take the picture and you put the camera down, and you make sure that that person is okay – I think that can be enough. I don’t want to stick to that because I also think there’s a lot more that could be done. But on occasion, those things work.

K.D.: I think the difficult thing is that you can’t know unless you have the hindsight of what that photo did. Both of those images are defining photographs of a period of time in society, and influenced a huge societal shift. But the photographer at the time couldn’t have known that.

E.C.: No, they couldn’t have known that. And yes, they did have an effect, but is it enough of an effect to justify it? I think probably not.

K.D.: It’s murky, isn’t it? Because with hindsight, you can say, “well, yeah of course it’s worth it, because it led to this huge change”, but without that hindsight, how can you know?

E.C.: It’s not just down to agency, but also how the images are disseminated. Sometimes it’s not enough to just hang a picture on a wall and hope the right person sees it. You have to put it in front of them, and you have to show them why it’s important. We can’t all just sit around as artists and tell each other why certain things are important, because the people that need to see it aren’t coming to your show. Galleries are fantastic, in all sorts of ways, but they don’t work when it comes to active conversation. You have to be more active. Otherwise, it’s not enough to have good intentions.

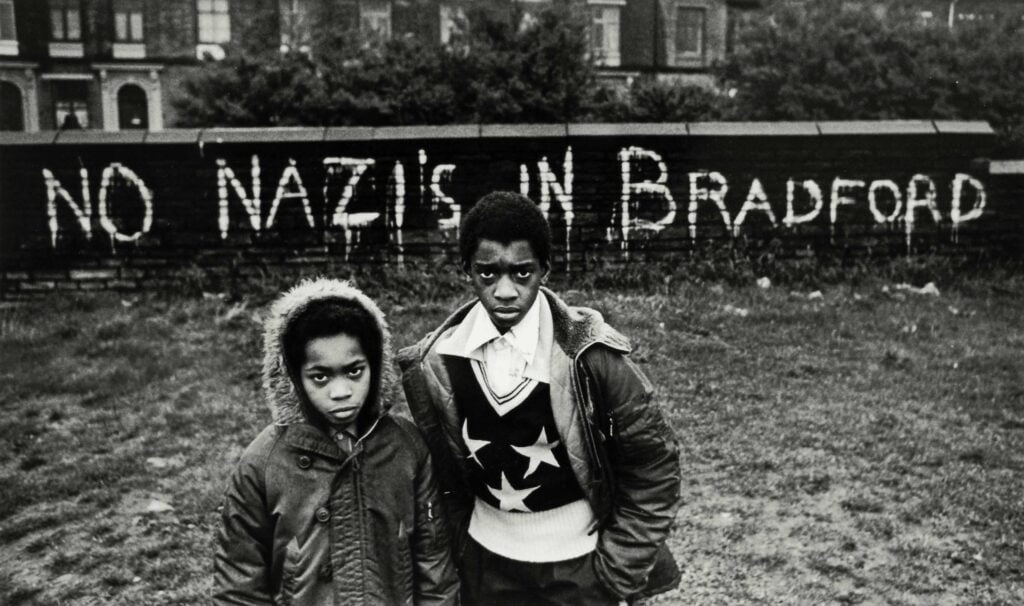

Don McCullin Local Boys in Bradford 1972 © Don McCullin

K.D.: And I guess that comes full circle back to McCullin’s photos being in magazines and newspapers rather than galleries.

E.C.: Yeah, that’s where they were initially and that was an active way of using them. People would be sitting around their dinner table drinking their morning coffee and then suddenly here’s a shocking photo. It’s incongruous, and that shocks you into wanting to take action.

K.D.: Exactly, and when you’re going to see a Don McCullin exhibition, you’re expecting to see those images, you’re mentally preparing yourself before you get there, whereas, like you said, if you just open a newspaper in the morning, it’s much more confrontational.

E.C.: And also if you’re sitting around with your family reading the paper, those images would spark so many conversations in a way that they might not in galleries. The problem is, like you say, we prepare to think about things in that space. I think that sometimes it’s great that we go there and we look at art with that more engaged eye, but sometimes it’s good to use it outside of those spaces as well to evaluate those same problems and have conversations in a way that people don’t in galleries.

K.D.: I think also as soon as something is in a gallery and is framed as art, people feel that they don’t have the right or the intellect to comment on it, galleries are intimidating spaces. So then when you’re putting work in those spaces, you’re presenting it to people who feel like they have a right to view it.

E.C.: My favourite gallery in the UK is the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. For the sole reason that families take their kids, they take their dogs, there are sheep next to Henry Moore sculptures, and kids climbing all over them. If that same sculpture was in a gallery, it would be roped off, and people would freak out at the idea of touching it. But if you’re five years old, and you see a big, weird metal shape, why is it wrong to climb on it? If you went into a gallery and all the walls disappeared – I mean, yeah, terrifying – but the meaning of the work doesn’t change. Galleries to me are a convenient space to store artwork, but when you start charging ticket prices, and intimidating people into thinking they can’t have those conversations, when you have to go through a gift shop and a cafe before you can talk to someone about what you think about the work, it loses it for me. Creating space where people can actually discuss what they’re looking at and the idea – that’s what the arts are for.

*After this conversation I did a little research and found that The Daily Mail, unsurprisingly, published an article titled “This child’s death was tragic but it was not our fault”, and that’s word for word.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: agency, artist, curator, documentary, Don McCullin, england, ethics, experience, gallery, liverpool, newspaper, North, photographer, photography, Poverty, press, shock, soldier, Tate, Vietnam, war

Comments