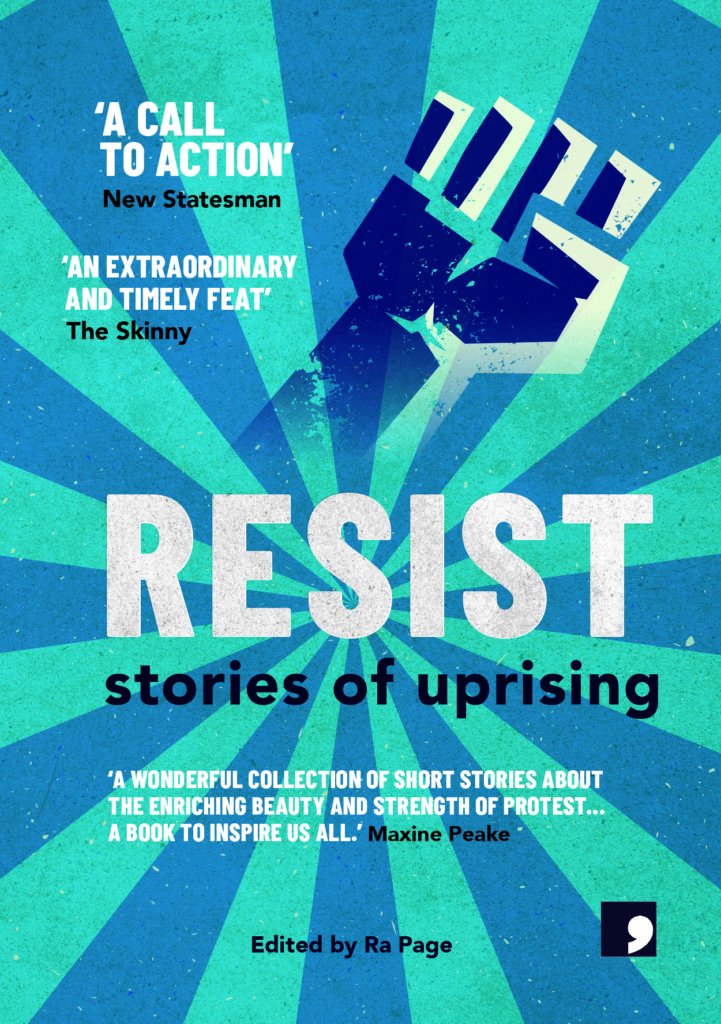

In October 2019, Comma Press will publish ‘Resist: Stories of Uprising’, the follow-up anthology to ‘Protest: Stories of Resistance’, introducing 20 new re-imaginings of key moments of British protest history, written by 20 acclaimed authors, each in consultation with a specialist to help them set the stories in a wider, historical context.

The protests in ‘Resist’ span from Boudicca’s revolt against Roman occupation in 45 AD, to the Grenfell Tragedy of 2017, and range from historical Welsh protests, Liverpool’s history of strikes and dispute, racially charged riots and murders, women’s rights movements and the beginning of climate strikes.

The collection features writers such as Kamila Shamsie, Luan Goldie, Eley Williams, Lucy Caldwell, Irfan Master and many more.

In this month’s column, we talk to three of the contributing authors and one of their specialists to gain more of an insight into the process of re-writing Britain’s history of protest, and the importance of undergoing such a task now.

Nikita Lalwani, author of ‘Two for One’ on the Tottenham Riots and the death of Mark Duggan.

Q: Where did your take on the Mark Duggan riots for this story originate from?

A: I read through all of the transcripts that came to me through Roger after our conversations about his research into crowd motivation during the Duggan protest and afterwards, and kept thinking about the moments where the consensus of the crowd around the red lines of protest is pushed and pulled in different directions. I wanted to put this complicated tornado of a situation into the domestic setting and locate the political in the personal – a wounded couple who don’t agree about their child’s involvement in the riots.

Q: How do you think your re-telling of the past re-contextualises current, similar issues?

A: There is something in understanding motivation – how it begins, grows, changes, goes back on itself and meets up with post rationalisation and/or regret in this protest and others like it that I found really compelling when writing this story.

Q: What was it like to work with Roger Ball on this piece? How did his expertise influence you?

A: Roger was an incredible resource – and his research is of huge value to anyone trying to understand how and why that particular protest began and grew into what would later be called the 2011 riots. I am indebted to him.

Dr. Roger Ball, Nikita’s specialist:

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your research background, and what makes you a specialist on the Mark Duggan riots?

A: I have been researching post-war urban riots in the UK for over ten years, first as part of my History PhD studies and more recently working with social psychologists on the Beyond Contagion project. The latter involves applying social identity concepts to understanding the spread of riots across cities and the country in August 2011 rather than reverting to outmoded (though popular) theories involving unconscious, disease-like mechanisms for the diffusion of collective violence. The remit for the work on the August 2011 disturbances required both detailed micro-histories of disorder events as well as quantitative, macro studies of all the riots. Unsurprisingly, the first case study we undertook was to look in depth into the disorders in Haringey in the aftermath of the shooting by police of Mark Duggan, the incident that precipitated a wave of around 100 subsequent riots. As a historian, I am a great believer in finding out ‘what’ and ‘how’ something happened before diving into the ‘why’.

Q: What was it like to work with Nikita on fictionalising this moment in history?

A: It was a breath of fresh air to work with Nikita. ‘Riots’ in themselves are problematic events because they do not necessarily satisfy the ‘protest’ paradigm and involve taboo-like behaviours such as property destruction, looting and even partying! I was nervous about fictionalising the riot in Tottenham because it was such a recent event, without the moderation of time, and represented as the unacceptable face of protest. However, I was able to speak frankly to Nikita about these taboos and the processes which transform protests into episodes of collective violence, and protestors into ‘rioters’. She quickly grasped the meaning of the Tottenham event for the friends and family of Mark Duggan and the dynamics of the interactions between the police and the crowd that fateful evening.

Q: What do you think of the finished piece, and the impact it might have on shaping current views?

A: Nikita’s take on the Tottenham ‘riot’ is fascinating. To step back from the event itself and consider the effect on the parents of the imprisonment of their son is a clever angle. It places the reader in the position of the parents in trying to understand second-hand how someone they love could transform from a ‘respectable’ protestor into a rioter and then looter. This set me up nicely to outline some of the recent research on these social-psychological processes. I hope that this piece will go some way to dispelling out-dated ideas of mindless, irrational or even ‘feral-like’ behaviours of crowds that were touted by many politicians and journalists during and after the riots of August 2011.

SJ Bradley, author of ‘Black Showers’ on the Oxfordshire Rising:

Q: Where did your take on the Enslow Hill Rising for this story originate from?

A: When I initially read about the Enslow Hill Rising itself, one thing that really interested me was the idea of a ‘failed rising’. What we know is that, though there was increasing landlessness and hunger amongst the peasants of this period, only four people attended the so-called “Enslow Rising” on the hill.

Initially this got me wondering whether there’s a British tradition and culture of apathy. Do we, as a nation, just generally not care enough about what’s done to us to get out on the streets and protest? I was really interested in thinking about whether that played a part in the failure of the rising, but when I tried to look more into what had gone wrong at the Enslow Hill Rising, I soon found out how little was known about peasants’ lives. Most working people of the time were uneducated. What information they had was spread verbally, and not written down. Most written records of the time were things like laws, deeds, and letters, written down by aristocrats, or those with an education. We have more written records left by Edward Coke, the attorney general who prosecuted those involved in the Rising, and therefore more known about Coke, than we do about the agitators of the Enslow Rising themselves.

Q: How do you think your re-telling of the past re-contextualises current, similar issues?

A: One of the things that really interested me in this story was its parallels with our lives today. During the 1590s, peasants were reliant on their land to feed themselves, and dependent on the wealthy aristocracy for paid work. During the period immediately before the Enslow Rising, The Enclosures Act meant that wealthy landowners in the Oxfordshire area had ‘enclosed’ more and more land for their own use, greatly decreasing the amount of arable land available for peasants. Several poor summers in succession meant that the peasants were without food and were starving; young people were leaving the villages if they were able, leaving them depopulated and empty, whilst the Lords were enjoying having barns full of corn and hundreds of acres of land to use as their own personal parks, and for grazing their sheep.

Whilst lots has improved since then – we have a better legal system for one, meaning more equitable access to justice, and improved access to education – some things have stayed the same or got worse. We’ve got people in this country who are in work and using food banks, whilst the super rich can use the capital they already have, and exploit the labour of others, to get even more super rich than they already are.

Q: What was it like to work with John Walter on this piece? How did his expertise influence you?

A: The only history I really knew before this process was mostly 20th century history. I didn’t really know anything at all about the middle ages. John taught me a lot about what life was like back then, how brutal it was, and how different from our lives now. As an author, I found myself approaching it the way I would writing speculative or sci-fi fiction. Creating the world, thinking about what would have existed then, and what would not have, and how that influences how people act in that world.

Luan Goldie, author of ‘The Done Thing’ on the Ford Dagenham Women’s Strike:

Q: Where did your take on the Ford Dagenham Strike for this story originate from?

A: Growing up in East London/Essex, the strike is part of your history. You know about it, though not really enough to talk about it in detail, but there’s a general understanding that not so long ago a group of everyday women were brave enough to stand up for themselves. So the idea of fictionalising this was quite daunting at first.

I knew I didn’t want to write a piece set in the sixties. I love history but didn’t feel that I could accurately write a piece set in a time period I didn’t live through. I also had it in my mind that these women were tough, they were unionists, they were balancing their work and campaigning along with being mums and wives, so I wanted that to be a big part of the story. Also and most importantly, I didn’t want to paint the women as these plucky, cheeky, Essex girls.

Q: How do you think your re-telling of the past re-contextualises current, similar issues?

A: Between the Gran, who was part of the strikes in the sixties, and the somewhat self-righteous and overly woke daughter, is Tony, the dad. He’s the bridge between the generations. So in the story you hear him get upset about feminism, not because he doesn’t think women should be equal, but because he doesn’t’ understand it. To him, the idea of change and marginalised people using their voices more just means that he’s always in trouble for saying the wrong thing, like referring to ‘girls’ rather than ‘women’. Tony is surrounded by women in the story, he loves women, but he’s put out by his daughter who always wants to talk politics and is still reeling from getting into trouble at work for complimenting a woman on her appearance. It’s like he’s worried about being left behind, just as some of the men must have felt back when the women started demanding equal pay.

Q: What was it like to work with Jonathan Moss on this piece? How did his expertise influence you?

A: Having an expert source of information on hand is an unusual, but amazing, way to write a short story. I had all sorts of ideas in my head before speaking to Jonathan and while I was excited to get some more context from him, I did feel anxious about it dictating the story too much. Though this never happened. I really enjoyed hearing about the climate of the time as it made the Gran character so much clearer in my mind. I also loved hearing all the tiny details the women had passed onto Jonathan through his interviews and research. For me, all I do is make stuff up, whereas Jonathan’s work is, obviously, the complete opposite. I was quite amazed at the kind of detail he could speak in about the strikes and the time period in general. All this information I pulled and attempted to seed throughout the short story.

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: author, books, Comma Press, expert, Fiction, history, northern fiction art alliance, Protest, resist, riot, uprising, women

Comments