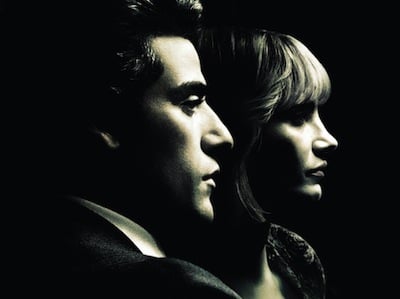

Pic: Darkest Hour via HOME Manchester

Darkest Hour tells the story of the weeks surrounding the evacuation of Dunkirk and Winston Churchill’s sudden rise to power. Facing a crushing defeat, Churchill delivers his famous speech and galvanises the British resistance to Nazi tyranny. So it’s a true story, set during WW2, about an iconic figure who overcomes the odds and cynicism of their peers, and said figure is played by a universally respected character actor. In other words, it’s premium Oscar bait. And while it is just as starchy and calculated as that sounds, it is, at times, undeniably affecting and rousing.

With the sheen that history has afforded Churchill, it’s easy to forget both just how dire Britain’s situation really was when he suddenly ascended to power, and just how much he was disliked and feared by establishment Conservatives and King George. Assuming power with Parliament adrift and in crisis, 300,000 British soldiers trapped in Dunkirk, and the very real threat of a full-scale mainland invasion, Churchill’s refusal to concede anything to the Nazis – while easy to commend in hindsight – at the time was actually a hugely unpopular and possibly suicidal notion that threatened the very existence of Britain. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine today, but a large number of influential members of Parliament favoured a peace deal with Hitler rather than face annihilation, in a time when the full horror of his rule was not understood.

What’s particularly interesting is the fact that the audience are made to feel a certain ambivalence about Churchill’s stance. Surely a peace agreement with favourable terms is more agreeable than the destruction that would surely entail continuing the fight? While history has cast a rather unfavourable light on figures like Chamberlain, the film is canny in the way it makes us understand and empathise with their views, rather than simply demonising them or portraying them as cowards; the idea of fighting a hopeless battle really does seem mad in comparison. And that’s important because it would have been all too easy to play it straighter and more unambiguous in its support for Churchill.

Gary Oldman looks almost unrecognisable as Churchill, and, somewhat predictably, he is very good. Oldman is a dazzlingly versatile actor who, unlike so many other actors, moulds himself into the character rather than the other way around (just look at his role in True Romance). But even in comparison to other similar what a transformation!-type roles where a few pounds of make-up and prosthetics substitute for an actual performance, Oldman manages to find something memorable and unique. Churchill is such a thankless and difficult role to play because, for a figure so iconic, he exists in cultural memory mostly through pictures and his famous speech. Therefore, it can be difficult to create a portrayal that is recognisable, yet distinctive and surprising (see Brian Cox’s reviled Churchill if you don’t believe me). You know him and you don’t. Yet, Oldman manages to hit the key points of the character as we know him and also to surprise us with his intricacies and complexity, bringing Churchill to life with considerable aplomb.

And to the film’s and Oldman’s greatest credit, it is made clear that Churchill, in many ways, was actually a rather limited politician: unpopular and uncompromising at a time when the country needed unity and strength. There’s a great scene where we hear snippets of different conversations about Churchill in Parliament. He’s “an actor in love with the sound of his own voice”; “delusional”; and a man who “stands for one thing – himself.” What’s most interesting about it is that the film clearly doesn’t wholly disagree with their views. He comes off as pig-headed and blustering at times because he was pig-headed and blustering at times. It’s a somewhat unexpected take of his character, and it’s particularly clever because it makes us face the uncomfortable truth that Churchill may have staked the country’s very existence on his sense of pride alone. But it is exactly this pride, the film argues, that contributes to his true strength: the power of his words and his ability to unite the people behind a common cause.

The film is perhaps lucky that the story it tells is tailor-made to be affecting and rousing, climaxing with one of – if not the – most famous call to arms speech ever. Not all true stories are blessed with cinematic moments such as this. And with film-making this competent, and a lead performance this good, it’s hard to hold too much against it despite its very consciously calculated attempt to be a prestige, awards season historical drama. Director Joe Wright is in fine form, remaining classily understated and willing to let Oldman’s performance do the talking rather than relying on gimmicks, and mostly transcending the starchy, generic tropes of similar awards season dramas like The King’s Speech.

I say ‘mostly’ transcends these common failings because it is not without issues. For one, this is Oldman’s film through and through, and – perhaps inevitably – his co-stars suffer in comparison. Lily James and Kristin Scott Thomas both appear as Churchill’s typist and wife respectively and while they’re both fine, they’re not given enough dramatic space to really make any mark. Ben Mendelsohn fares better as King George, but only because he’s given more to do. The film’s most grievous misstep, however, is a bizarrely conceived scene near the end where Churchill rides on the tube to gauge the public’s opinion on the war. While one has to grant some artistic license in stories like this, portraying Churchill as a man in touch with the common people was probably a step too far. Moreover, it’s played as the moment when Churchill realises – through the honesty and bravery of his fellow passengers – that he must continue the fight against Hitler rather than submit, which, for my money, felt maudlin, mawkish, and downright dishonest. To go and suggest that his possibly suicidal decision to keep fighting Hitler was actually the result of a meeting with the common people leans far too much into the lionised, History Channel version of the character which the film had, up to this point, wisely stayed away from.

But beyond some weird decisions late-in-the-game that diminish some of the interesting character work that had been established beforehand, it’s an undeniably solid drama with a great turn from Oldman and a climax that would get anyone – though British audiences in particular – jumping out their seats. At an earlier point in the film, an angry colleague incredulously argues the insanity of Churchill trying to fight Hitler with “words, words, words alone!” It is those words, the film argues, that might have been just enough.

Filed under: Film, TV & Tech

Tagged with: Darkest Hour, film, Gary Oldman, Historical Film, HOME, homemcr, Joe Wright, manchester, Winston Churchill

Comments