Quarantine are a Manchester based ensemble of artists and producers who have been making original theatre since 1998. 12 Last Songs, is a 12 hour piece where workers perform their paid shifts on a stage, whilst being asked 600 questions. It is being performed at HOME on 24th September 2022 from 12 midday to 12 midnight.

12 Last Songs aims to capture a ‘fleeting portrait of society as a live exhibition of people’, and this prompted my discussion with director Richard Gregory.

Photo credit: Lowri Evans

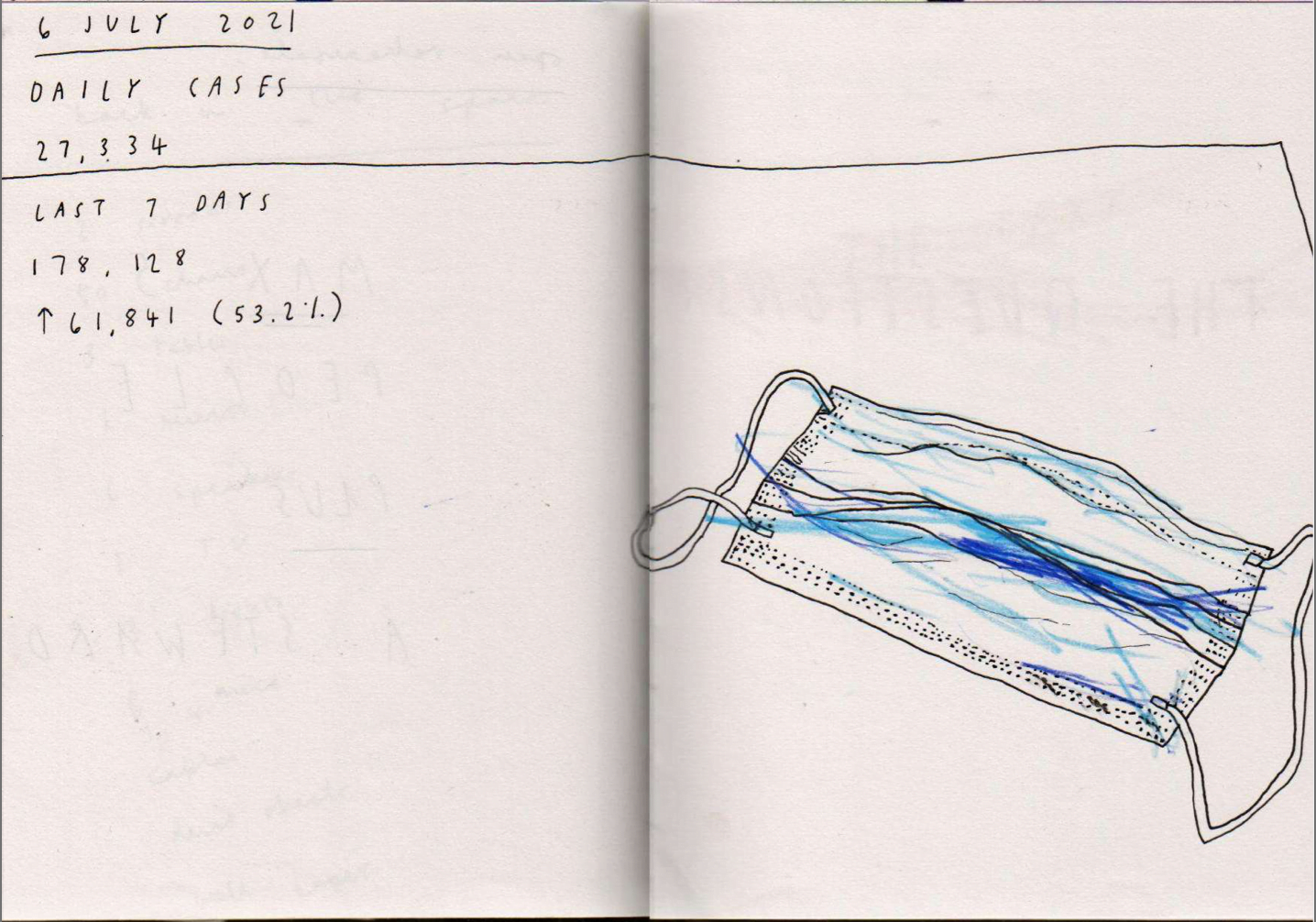

From the sketchbook I can see that you began the creative process during covid? What was this like and how did this influence your performance/creative direction?

The big shift was how the subject of ‘work’ took on a huge resonance, particularly during lockdown. We actually began working on the project before the pandemic. The first version was supposed to happen at HOME in March last year, but of course that got delayed.

Early on we decided on inviting people in because of the work they do, because it’s a way of finding people from all walks of life. And then when the pandemic happened and people started to clap for the NHS and notice the importance of supermarket workers and delivery drivers etc., the subject of work took on a sharper focus. Sadly I think as a society we seem to have very swiftly forgotten some of those lessons – the response to recent strikes being a good example of how quickly we seem to shift our focus and our values…

What is the process of gathering the people who are involved in the performance?

We broke the list down into certain categories – e.g. “morning jobs”; “skilled manual jobs”; “political jobs”; “jobs involving children”; “cerebral jobs”; “night-time jobs” etc. Then we start to think of who we might know, who might know someone who might know someone else who might fit into one of those categories.

We do it in this way because over time we’ve learned that having some kind of connection or relationship from the outset helps to build a sense of trust. We mostly try to avoid the idea of the ‘open call’ because they tend to not really be very open at all – often only reaching or attracting the ‘usual suspects’, people who already know that they want to do this kind of thing. We’re not interested in that quality – there’s plenty of other outlets for people who want that. We’ve found that personal contact is vital for what we do. For 12 Last Songs in Manchester we’re interested in where power lies (or indeed doesn’t…) in the city.

What is your intention with the theatre you create?

We try to create the circumstances for conversation between strangers, often bringing people together who might not normally meet. All of the projects somehow contribute to making a complex, kaleidoscopic portrait of contemporary life. It’s important that this fragmented portrait – across a 24-year history and dozens of projects – makes space for all kinds of people.

Photo credit: David Lindsay

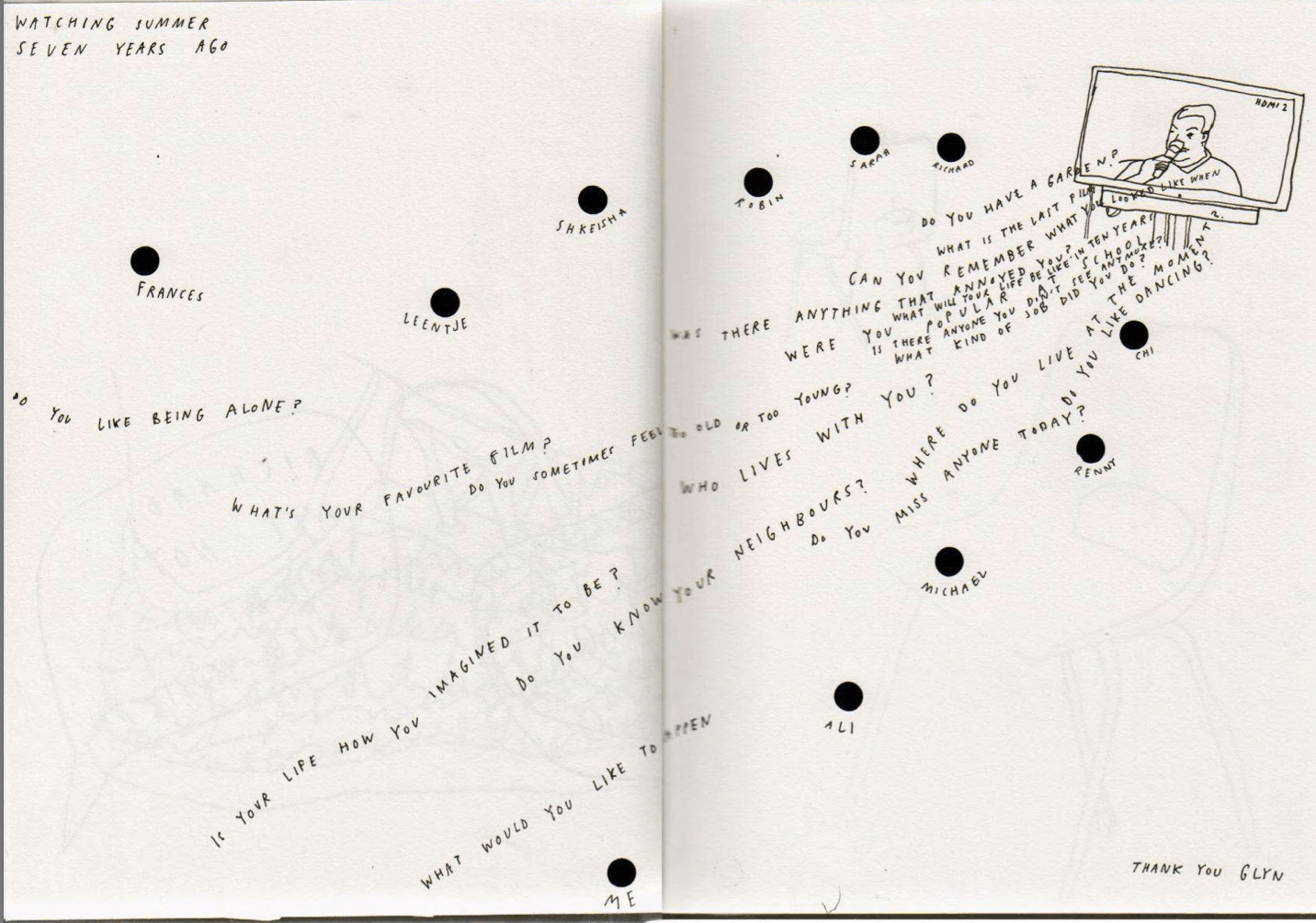

What was the process of deciding the 600 questions?

We’ve used questions as text a lot. They let us make a dramaturgical framework that holds the trajectory of the work, aware that we don’t know what response each of the workers will make to them. Across 12 hours, they move from questions about the start of a day, the start of a working day, the start of a working life, the start of life through to questions about the end of a day, the end of a working day, the end of a working life, the end of life….

We created the questions through discussion in rehearsal, trying them out in practice with workers that came into rehearsal. Then our dramaturges – Sarah Hunter, Renny O’Shea & Leentje Van de Cruys (who’s also one of the performers) – pulled all 600 together (with a bit of input from me). If you hear all the questions read one after another, it works as a single text.

A well experienced theatre company like yourselves, after creating for 24 years, have you found any challenges or difficulties when adapting with the world around you?

Responding to what’s happening right now in the world has always been a fundamental part of what we do. It’s one of the reasons we choose to work in a live medium that allows us to create with a sense of immediacy and directness. In the last decade our work has focused on making situations where the content emerges live during the event – we carefully make the form, the structure and the provocations in rehearsal, but we deliberately don’t know what the performers – who are all kinds of people – might do or say in the moment.

Of course the pandemic has thrown huge challenges at everyone. We were forced to pause and adapt and rethink certain projects. For example, in 2020/21 where we were supposed to make residencies in 7 European cities and ended up not being able to go to any of them! However, we were fortunate to be able to keep going and continue to make work – like 12 Last Songs – that talks about being alive right now.

With the piece being 12 hours long, how did you decide that the piece was complete or is this piece ever complete? Does it change every time you perform?

The version of 12 Last Songs at HOME will be absolutely unique – starting at noon & (if we get it right!) finishing exactly at midnight. This version will be complete at midnight on 24th September. Each version takes the same structure and the same set of questions but of course the content changes hugely because the 24 workers are different in each city – except in Manchester, we have the same painter and decorator, Jane, who was in the show in Leeds – because she’s brilliant at what she does, was really fascinating to talk to – and we felt like we had more questions for her.

So – as a piece of work it’s never complete. That’s why we continue to be excited by it – each time we need to really pay attention to what the next one might become. We have dates lined up next year in Strasbourg, Cambridge & Gateshead, and it looks like there will be versions in the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, Egypt, Australia maybe. It’s fascinating to think about what portrait might emerge of all those people in all those places.

Photo credit: Lowri Evans

Who is your audience and why? Due to the duration and the planned time of the piece do you have any concern as to how many people will attend?

I know very well that there are all sorts of barriers for people with the very idea of coming to see ‘art’ or ‘theatre’. So many people feel like it’s not for them – an ongoing problem, trapped by ideas about class and culture and not helped by the ways that much of art and theatre presents itself. One of the things we’ve found over time is that if you invite people to be involved who might not normally do this kind of thing – in this case, the workers in 12 Last Songs – often their family, friends, neighbours, work colleagues etc. will come to see them in it. That creates a new kind of audience and an atmosphere that I really enjoy. There’s nothing worse than being stuck in a room with people who know exactly what to expect and have a fixed idea of how you should behave – the new audience can really break that, which is great.

What we’ve found in the previous versions in Leeds and Brighton is that people attend in all kinds of ways – popping in for an hour and that’s all; coming for an hour or two, going away & then coming back later; and a surprisingly large number of people who stay for the whole 12 hours! I’m sure they nip out for food or to use the toilet but otherwise they’re present throughout.

Past audiences have described it as ‘addictive’ with one saying he ‘planned to stay for an hour, ended up staying for four and wished he could have stayed for much longer…’

After researching the concept of the piece I wonder if there were any ethical implications that you had to consider? If so, what were they and how did you take these into consideration?

We try to take our responsibility for the people we work with and the workers we invite in seriously and with care. A vital thing is to try to ensure that everybody fully understands what it is they’re being invited into and that they have agency in how they might respond to the situation, especially when they’re being asked questions live in front of an audience. It’s an unfamiliar situation for most people so much of our rehearsals were about developing our performers skills to deal with that with sensitivity.

And – perhaps a territory where ethics, politics and economics overlap – we pay all of the workers at the same rate of £25 per hour, whether they are a politician, midwife, cleaner, surgeon, plumber or property developer.

***

It was a pleasure to understand Quarantine’s process of working and how they have created such a unique and dynamic piece. This performance is a ‘pay what you can’ and tickets are available via this link.

You can view the trailer to 12 Last Songs here.

Filed under: Theatre & Dance

Tagged with: 12 hour, community, creativity, homemcr, performance, quarantine, shift, stage, theatre, workers

Comments