Fernand Léger, 1881-1955 Two Women Holding Flowers 1954 Oil paint on canvas 972 x 1299 mm Tate. Purchased 1959 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 201

A sense of excitement, and a thrill for modernity proliferates in Fernand Léger’s exhibition ‘New Times, New Pleasures’, currently on display at Tate Liverpool.

Depicting the noise and dynamism of the modern age in the early 20th century, Leger’s work is filled with movement, colour and bold lines; an interest in depicting dynamism is balanced with exploration of the figure.

As I navigated Tate Liverpool’s selection of the French painter’s work it became clear that his Cubist style overlaps with a preoccupation with figurative representation, a characteristic present throughout a significant period of modern history – the machine age. Although painting was Léger’s technique of choice, the exhibition also highlights his interrogation of the mediums of film, printed books and textiles alongside a nod towards his contribution to postmodernism in collaborations with Man Ray and film director Dudley Murphy.

The show begins with the period in his practice nicknamed ‘Tubism’, a term coined by the art critic Louis Vauxcelles to describe Leger’s style, originally meant to ridicule his work by referring to the artist’s preference for cylindrical shapes and robot-like figures.

Léger’s later collaborations and large murals are a contrast to his earlier work. This can be seen in the painting ‘Study for “The Constructors”: The Team at Rest’ (1950) which centres around labour and the suggestion of modern improvement. To some, it can also read as a symbol of cultural acceptance of the unity of technological progress and the organic world.

Fernand Léger, 1881-1955 Study for ‘The Constructors’: The Team at Rest (Étude pour ‘Les Constructeurs’: L’Équipe au repos) 1950 Oil paint on canvas 1620 x 1295 mm Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh. Purchased 1984 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018. Photo: Antonia Reeve

Léger’s early enthusiasm for the machine age is juxtaposed with other notable artists who worked during the war, including painters from the German Expressionism movement who, like Léger, were involved in military service. Their practice, like that of Ernst Kirchner, often resulted in paintings full of anxiety, fear and tension. Kirchner’s work exudes emotion with dramatic brush marks and vivid tones that often appear somewhat intimidating, unlike Leger’s flowing shapes and primary colours.

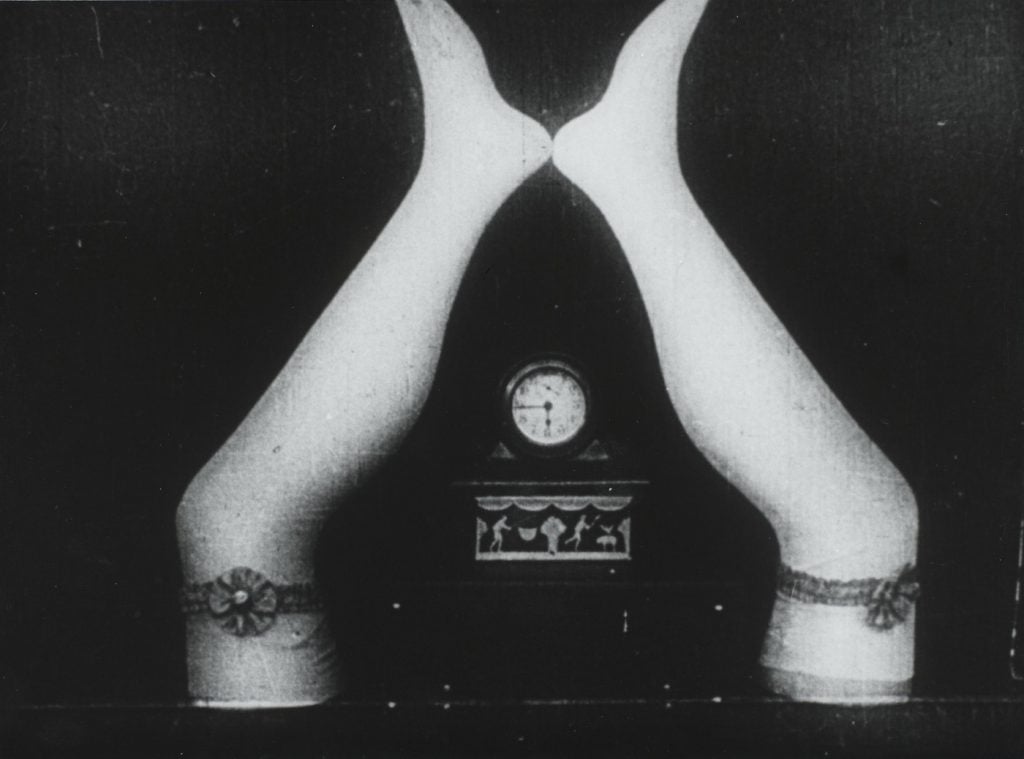

Parallel to Legers investigation of modern life with machinery, an equally intriguing discovery at the exhibition was his experimentation with film in the early collaborative piece titled “Ballet Mécanique” (1924) in which the Post-Cubist visual language and narrative were formed with Murphy and Man Ray. The film was a particularly memorable part of the exhibition due to its unnerving, fast-paced musical score. Abstractly paired with mysterious clips of a woman on a swing cutting to frames of rotating shapes and objects, the film left a feeling of confusion that made the experimental nature of the collaboration more obvious.

Fernand Léger, 1881-1955, George Antheil, 1900-1959 and Dudley Murphy, 1897-1968 Mechanical Ballet (Le Ballet mécanique) 1923-1924 35 mm film, 13 mins © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018. Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI

The inspiration Léger gained from his experiments with film is reflected in the layout of the exhibition, which reveals how his subsequent work gained a hint of cinematic movement. Despite being displayed on a flat surface, it remained full of atmospheric liveliness. Prior to his experimental film, I could sense the artist’s desire to capture movement and a certain atmosphere, for which the two-dimensional tools of painting are not always enough.

Another aspect of Léger’s remarkable artistic achievement was his belief in improving accessibility to fine arts; understanding the value of developing a practice that can reach out to audiences regardless of identity and class. The exhibition addresses this with a selection of printed books and graphics including “Broom”, a printed publication that ran from 1921-24 that introduced European Avant-Garde artists to America, making sense of a new cultural shift.

Léger’s diverse contribution to the arts was made in the years during and after the World Wars amid the new waves of technology that followed, when the sensations of pleasure and curiosity within European art were restored, eventually leading to more experimental movements such as Pop Art and increasingly popular crossovers between film and contemporary art.

In this exhibition selected significant components of Léger’s career have been robustly interrogated to achieve an understanding of his fusion of day to day life with his interest in technological advancement. The show helped me follow the development of Leger’s practice while providing context for why his work changed so drastically. Perhaps more from his collection of prints and work in publications could be a successful addition so we can gain a better appreciation of another aspect of his multidisciplinary career.

‘New Times, New Pleasures’ is on display at Tate Liverpool until the 17th of March. You can find out more here.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: avantgarde, cubism, Experimental, fernand leger, film, man ray, modern art, painting, Tate, tubism

Comments