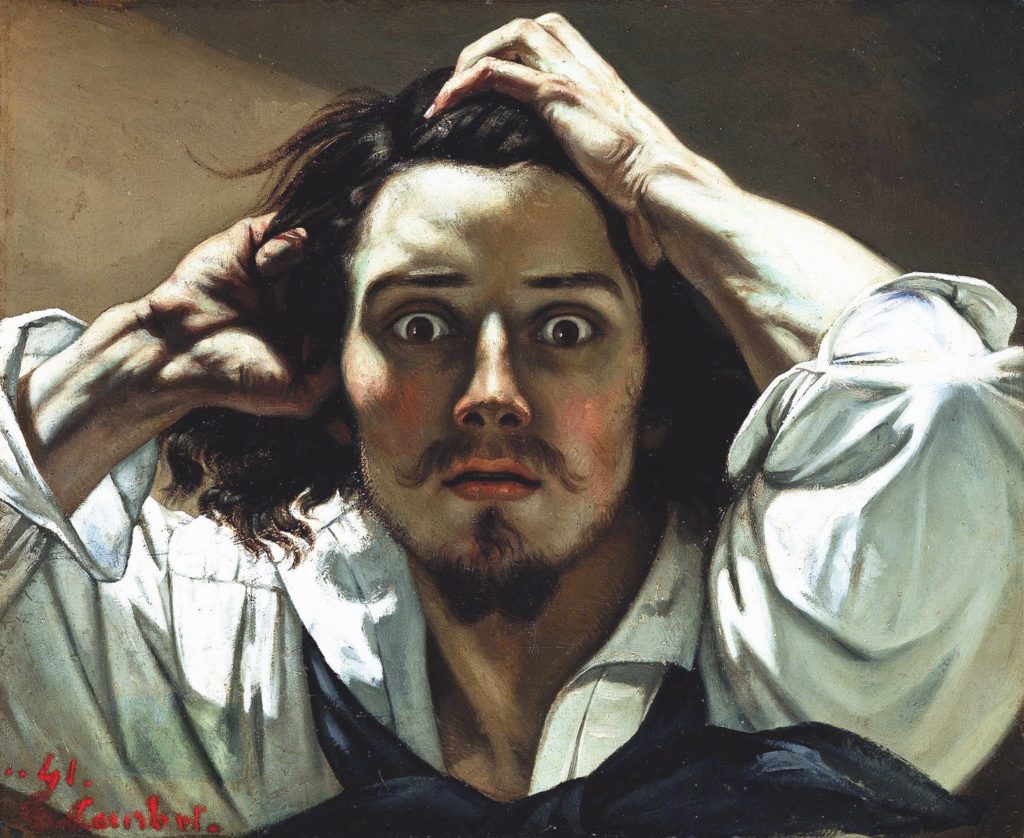

Gustav Corbet, ‘Self Portrait (The Desperate Man)’, c. 1843–45

The trope of the mad genius is a familiar one. From wild-eyed professors to obsessive and socially inept detectives to, perhaps the most prevalent variation of all, the ‘tortured artist’: the brilliant and radical painter, composer, or writer pursued by dark and unrelenting demons. It’s a tradition that spans the centuries, from Dürer’s ‘Melacholia’, to Gustav Corbet’s ‘Self Portrait (The Desperate Man)’ and Munch’s infamous ‘Scream’. For the Romantics, the badge of the melancholic, deeply feeling artist was worn proudly, a sign of artistic authenticity, and then in the era of Expressionism, during and after two world wars, the trope became darker, and more extreme.

When we fictionalise, or attempt to reimagine the lives of troubled artistic giants, there is an almost ubiquitous tendency to draw a direct link between their mental health battles and the astounding quality of their work, as if one were the direct result of the other. But, as the recently closed exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum has emphasized, that relationship is far from simple. The reality is much more complex, and there is a stark difference between navigating Dryden’s ‘thin partition’, and tumbling through the other side.

A quick Google search floats a raft of ‘scientific’ research on the matter—it’s the kind of clickbait science that tabloids and broadsheets alike love to overstate. In 2009 it was reported that scientists had discovered a gene that was linked to both creativity and schizophrenia, yet at the same time multiple studies also conclude that creativity is negatively affected by low mood. Similarly, while one research project suggests that the occurrence of mental health problems in artists is no greater than in that of the general population, others (Kay Redfield Jamison’s ‘Touched by Fire’) conclude that mental illnesses are 10-30 times more prevalent in artists. The fact of the matter is we have grown attached to the image of the manically scribbling virtuoso in emotional turmoil. A disheveled, unkempt aesthetic, and outlandish unpredictable behavior are considered the markers of a true artist and when we see a black and white group shot of the Surrealists attired in suits, ties, and spectacles, looking like bank managers and their secretaries, it jars with our sense of the artist as outsider, as eccentric, and necessarily a little unhinged.

‘The Surrealists’, New York Fall, 1942. Photo: Hermann Landshoff

There is a presumption all too often that it is the madness that makes the artist. That the dual forces of mental instability and creative brilliance are a double-edged sword with which the true artist is simply, born. What if, by contrast, it’s the very life of an artist that seemingly leads so many to the brink?

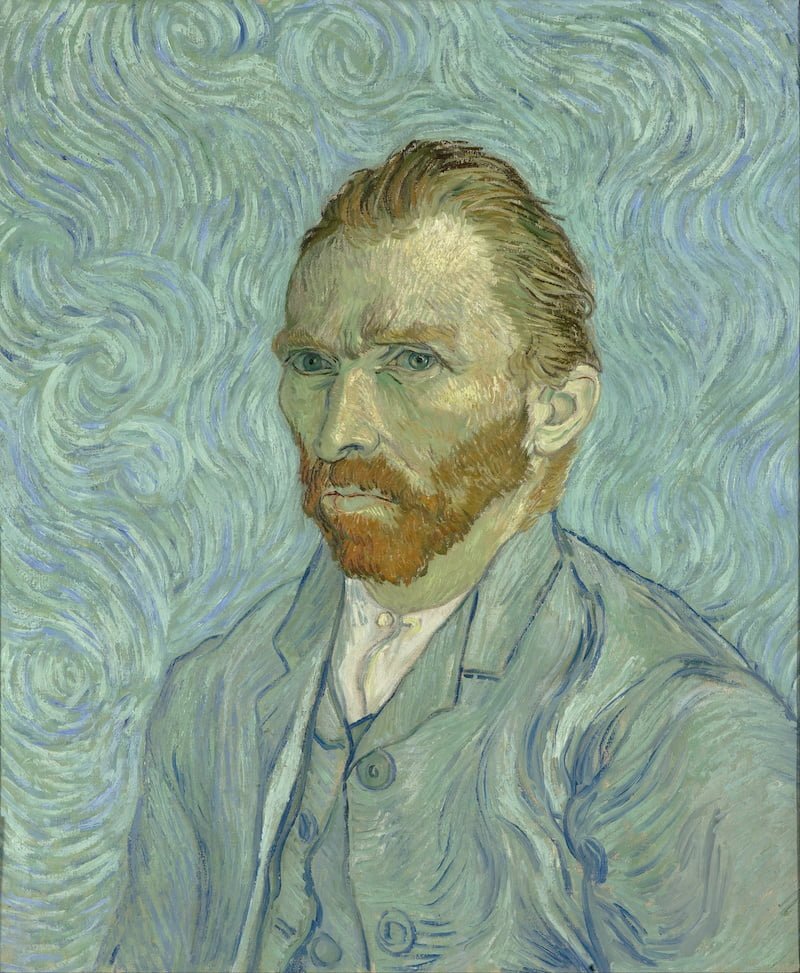

After his most significant break down whilst living in Arles, Van Gogh’s doctor diagnosed him as ‘suffering from a form of epilepsy brought on in part by too much coffee and alcohol and too little food’. Historically (and arguably still today) an artist’s existence has been one of instability, poverty, malnutrition, and constant self-doubt. Do these not seem like the perfect conditions for tipping someone over edge?

It’s true there are rich artists for whom commercial success has come within their lifetime, but this brings its own battles. After all, less than a decade after Time Magazine suggested he was the world’s ‘greatest living artist’, Jackson Pollock had died in a car crash after two fitful years of drink and depression, and in 1987, two years after he appeared on the front cover of the New York Times Magazine, Jean-Michel Basquiat was dead from a heroin overdose. This is not say that if you choose the career of an artist you are doomed to premature death (just look at Dalì, commercially successful and successfully odd until 85 years of age!) but we do tend to focus on the macabre stories with more fervent curiosity. We don’t romanticize the high occurrence of mental health issues in the teaching or health care professions, so why the creative pursuits? And is our expectation that those who suffer from mental health problems, a whole quarter of the population, should necessarily have an artistic genius in them somewhere?

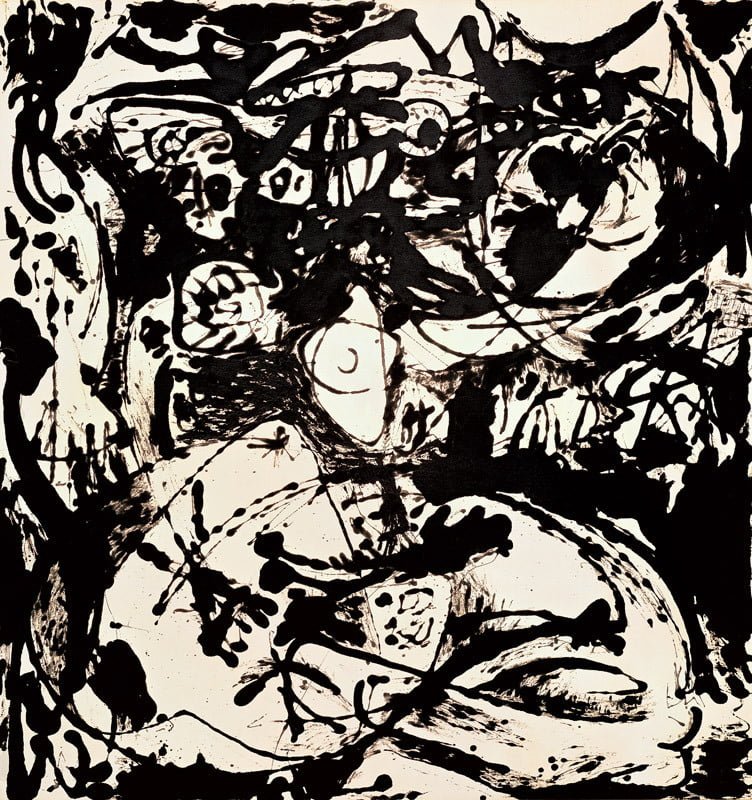

Jackson Pollock, ‘Number 18’, 1951,

To have an ‘artistic temperament’ is a by-word for both the infuriatingly self-obsessed and the genuinely ill, and much like TV portrayals of high-functioning autism can do more to hinder than help our understanding of the condition, our Hollywood-isation of the tumultuous artist can do more damage then good. We should be opening up our discussions on mental health, to some degree normalizing it, as you would for a broken arm or a bout of flu, not over-emphasizing innateness or the doomed trajectory of the brilliant, mad artist. As Van Gogh wrote in a letter to his brother in 1889, “I well knew that one could break one’s arms and legs before, and that then afterwards that could get better but I didn’t know that one could break one’s brain and that afterwards that got better too”. Clearly Van Gogh’s wellness was no long-term achievement, but to read these words from a man whom popular culture has so saturated with insanity, is quite an eye-opener.

Vincent Van Gogh, ‘Self Portrait’, 1889

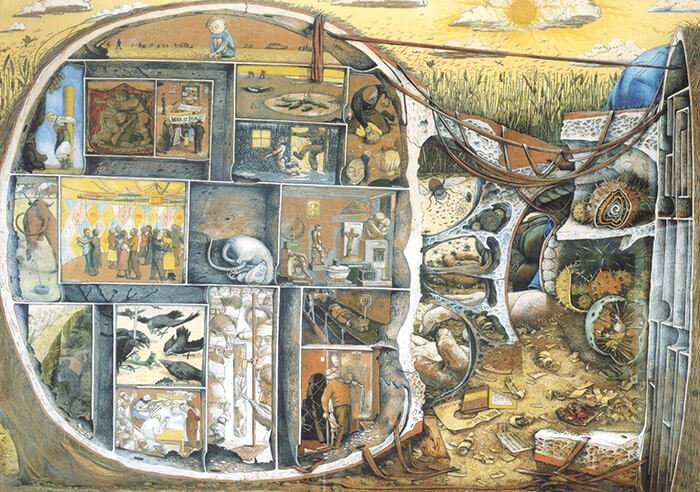

The truth is that for artists, and for anyone suffering with depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, what ever it may be, it takes a heavy toll. Many view the black, frenzied, and blotchy paintings that Pollock undertook in his heavy drinking years post-1950 as a stupendous plummeting from the peak of achievement, but on the other side of the coin, Canadian artist William Kurelek is best known for his painting ‘The Maze’ which was produced inside a mental health institution. While many artists have found that they simply cannot work when in the grip of a psychological crisis, others confronted with the dark abyss see it as a well from which to draw, and for others still, it is the key, or at least a part of the key, to recovery.

An exhibition at the Wellcome Collection, entitled Bedlam: the asylum and beyond opened in London last month, and will run until January 15th 2017. The exhibition delves into the rise and fall of the mental health institution in this country, taking the most famous, Bethlem Hospital as a central point, and exploring the work of pioneering psychologists, patient testimony, and art.

William Kurelek, ‘The Maze’, 1953

The exhibition highlights the work of pioneering art therapist Edward Adamson, showcasing work from the Adamson Collection, pieces produced by patients at the Netherne Hospital in Surrey in 1946. Adamson’s view that mental health problems could be managed and even cured through art was groundbreaking. While others saw the paintings as useful tools for potential diagnosis (it was thought that schizophrenics would use more red for example), Adamson’s insistence on the use of art as alternative to medication or surgery was well ahead of its time, and since the intervening decades have seen more and more research and personal testimony that attests to its efficacy, art therapy is increasingly available through the NHS.

It seems, then, that the relationship between art and madness is intimate and complicated. From melancholic romantics with ample yearly allowances, to impoverished Post-Impressionists, and alcoholic drip painters, art has had a historical role to play in the cause and exacerbation of mental instability, and now it seems, it can also prove the remedy.

Comments