The Story of ‘Selling Out’: popular music, advertising and the Walkmen

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the use of popular music in advertising was the main focus of selling out debates. While there had been some high-profile cases in the past – the use of the Beatles’ ‘Revolution’ in a 1987 Nike ad was for many fans an unwitting lesson in copyright ownership– ‘sync’ placements became a common strategy for advertisers by the late 1990s. A Volkswagen ad featuring ‘Pink Moon’ propelled singer-songwriter Nick Drake to posthumous fame; Moby licensed every song on his 1999 album ‘Play’ for use in screen media, including advertisements; and indie-pop artist Feist was one of many musicians to find widespread exposure through use in an Apple iPod ad. In this period, the possible stigma of selling out to a commercial company was weighed against the specifics of an ad (the reputation of the company or product, the artistry of the ad) and the potential benefits an artist might reap (the fee for the sync license, album sales, radio play). The use of music in advertising was so hotly debated in discussions about changing practices in the music industries that I wrote a book about it.

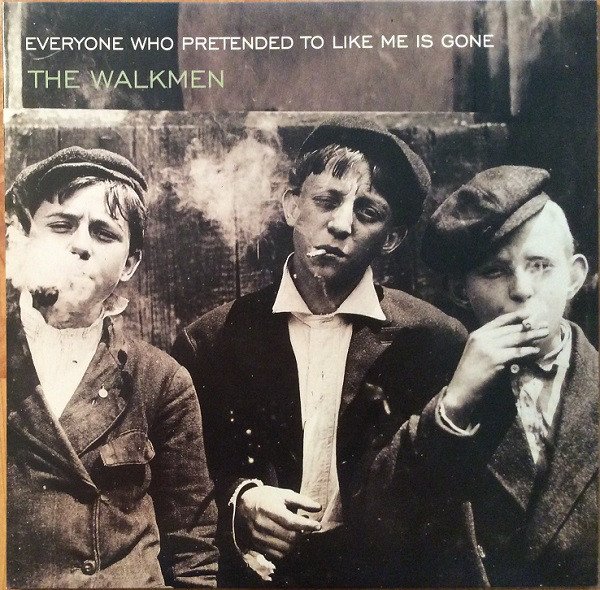

The example of the Walkmen and Saturn offers a handy illustration of when a placement works out well. The New York-based indie rock group licensed the song ‘We’ve Been Had’ for use in a 2003 commercial for the car company’s Ion model, with positive results. Although singer/guitarist Hamilton Leithauser anticipated that some people would think the sync “was lame and we’d lose a little respectability in the, whatever, rock world”, any criticism was muted and benefits were plenty. Isaac Green, owner of the band’s then label Startime International, explained that there was a direct correlation between ad plays and record sales, and although Leithauser was not convinced it led to much radio play (a later single got more), the fee gave the band a useful cash injection while they recorded their next album. It helped that all the pieces fell into place: since cars are a key site for listening to music, car ads offer a more natural fit for music than some other products; the ad, which featured a car full of young adults driving through scenes of childhood, was affecting; and the song, which fit the ad thematically, is great!

The group’s sync experience no doubt informed future opportunities: the Walkmen, members’ subsequent bands and solo efforts have featured in popular television programmes and ads.

While the success of bands following sync placements was cheered by many in the music and advertising industries, the normalisation of popular music in advertising had serious consequences for the potential benefits. Just a few years after the Walkmen placement, Startime’s Green explained that where once ‘the ad agency was compensating the band for the damage they would be doing to their career. No one feels that way anymore.’ Success stories instead brought closer to reality the joke that bands should be paying advertisers for the exposure: as the stigma attached to licensing lifted, the one guaranteed benefit, the sync fee, decreased.

Debates about the use of popular music in advertising were often marked by claims that there is no such thing as selling out anymore, a contention that has ushered in an era of artists partnering with brands and presenting themselves as brands through a dizzying array of promotional opportunities, but at what cost? As Dorian Lynskey wrote in a 2011 Guardian piece, “In the past, the idea of selling out could be too unyielding and punitive. But if we say that there is no room for it any more then we’re also saying there is no dignity in saying no, and no principle more powerful than the logic of the market”. Rather than dismiss the concept of selling out, we should take seriously the principles its use has sought to protect.

This is the fourth in a series of posts about the concept of ‘selling out’ in popular music culture in advance of the August publication of ‘Selling Out: Culture, Commerce and Popular Music’ by Bloomsbury. You can read the previous post, which considers rap, commercialism and Public Enemy, here. Follow @bethanylklein on Twitter and register for the 6th August online book launch here.

Filed under: Music

Tagged with: adverts, book, commercial, criticism, Feist, launch, Moby, music, music label, selling out, The Beatles. Nick Drake, The Walkmen

Comments