Travis Scott’s gig in Fortnite, source

What role has music played in your life over the past few months? I polled my Instagram followers a few weeks back and found a mixed bag: some were listening to less music (less commuting, less socialising), some more than ever (more time to listen, more need for the company); some were using the time to discover new artists, whilst some were clinging to failsafe favourites, playing albums on repeat for the comfort of familiarity. Back in March, Spotify streams dropped by 8% since lockdown began, with radio listener figures rising by 18%. Physical album sales plummeted alongside digital streams, whilst music video views shot up by 12%. It’s a confused set of figures for a confused time. The one clear insight? The crucial part that music plays in our daily lives: Our routines change, so do our listening habits.

So what happens when live music is taken away from us? Music is a thread that runs through our days and lives. Through headphones and aux-cords, yes, but also, perhaps more memorably, through pub gigs and club nights and summers full of festivals. 9 months ago, the UK live music industry was valued at its highest ever, at £5.2bn, contributing £1.1bn to the economy (not to mention the unquantifiable cultural and emotional value it produces). It doesn’t need me to spell out how deeply the industry has felt the impact of the past months: us loyal punters have all felt it too.

The response has been fascinating to watch. The internet, suddenly the only music venue open for business, has come alive in a way we haven’t experienced before. Twitch reported that audience numbers for music and arts livestreams grew five-fold in March alone, with Instagram reporting a similar surge in Live users. So what does this mean for the live music industry? And what does it say about the ways in which we will consume music going forward?

I started off by speaking to Ben from Readymeal, a Leeds-based collective and music label. Live music is in their DNA: they started out performing together at local venues, regularly playing Sunday nights at East Village, a much loved bar and venue that has fallen victim to COVID-19. Faced with a festival-less summer, they started to consider how they could use their time to support the struggling industry. “We started ringing up venues and being like ‘we can’t come and play with you, so would you be interested in joining us on this live stream?’” Soon, they had organised a virtual tour, seeing them partner with pubs and bars across the country to raise money for Save Our Venues.

They weren’t the only ones. Digital gigs, as a form, can be celebrated for their ability to break down the barrier between artist and audience, and give access to those who may not otherwise be able to view such music live. It breaks down barriers to access for performers too, which can never be a bad thing. But in a sea of livestreams, what makes you stand out? Ben says “there are a lot of people that do, like, acoustic guitar and an iPhone, which is brilliant – it’s obviously always brilliant seeing music – but you don’t get the atmosphere. You basically have to compete with what someone would want to watch on TV, which is quite a hard thing to do. We knew we could make it a higher production value – which makes more sense for these venues to come on board and support the whole movement.”

The comparison that Ben drew between the hundreds of music live streams that we saw over lockdown and the live music that we’re used to seeing on TV – Jools Holland, Top of the Pops and the like – was interesting to me. In recent months, virtual gigs and events have been used by organisers and audiences alike to try and fill a live-music sized hole in our lives. But this format is nothing new. Channels posting high-production videos of live performances, like Boiler Room, NPR Tiny Desk and Colours, are a form of music consumption in and of themselves, and have been popular for years. During lockdown, they came into their own – Boiler Room’s Streaming From Isolation series has featured sets from 120 artists to date, raising money for the likes of Global FoodBanking Network and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund – but it wasn’t anything new. Speaking to members of The Identification of Music Group – a community of DJs and dance music fans – about their increased consumption of live streams during lockdown, they all echoed the same sentiment: there is undoubtedly a place for live music on the internet, however, for the majority, it is a necessary, and wholly temporary, fix. You only have to look at the #SaveOurVenues tag to see how this surge in digital music events is fuelled by a yearning for the physical.

It’s true, but it’s not the whole story. Back in April, Travis Scott’s record-breaking Fortnite concert drew in 12.3 million live attendees, and 27.7 million over the full 5 days of concerts. An audience equivalent to 51 times the size of Glastonbury, or 3 times the size of London, is no joke. The show was a spectacle, taking players on a 15-minute, perspective warping ride around the Fortnite universe, from land to space to underwater and back again. And the timing was perfect, allowing hoards of players to escape the confined reality of lockdown and commune in this psychedelic alternate world. Whilst the concert remained traditional in the separation between performer and audience (the UI was suspended for the duration of the concert, allowing players to express a limited range of moves and emotes) it nevertheless represents a key moment: people choosing to experience music not just via a screen, but via an entirely separate virtual universe. Are you skeptical? I was. But if you listen to the commentators, Fortnite represents a key moment in the dawn of the metaverse, a development of the internet as we know it that will consist of a virtual universe that sits parallel to our own.

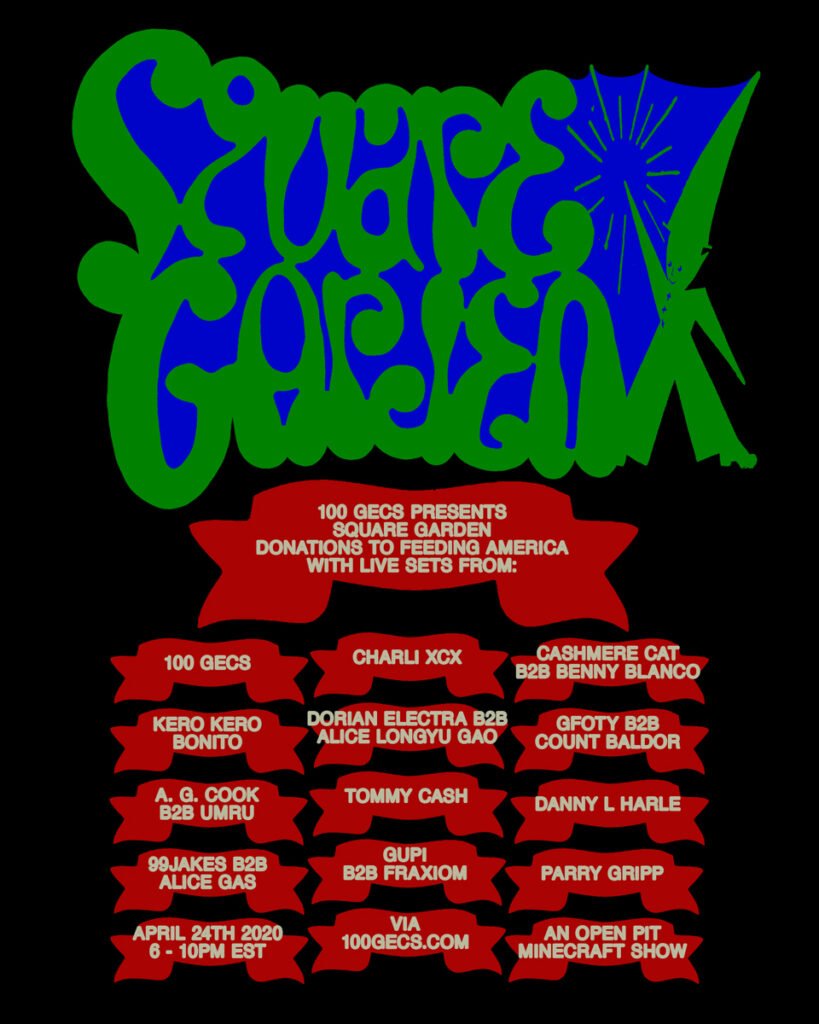

Poster for music festival in Minecraft, source

Whilst we sit here yearning for the sweat and shouting of live events, the inevitability of such a development feels far off at best, undesirable at worst. I spoke to an artist who recently played a set in Minecraft, who said: “As an interactive and immersive virtual experience it’s really cool, but I for one cannot wait to get back to playing irl. Isolation has definitely made me understand how crucial the live scene is to music”. But there is a real market for it. Minecraft regularly plays host to whole music festivals, particularly ones that cater to alternative music scenes. Lockdown has seen a real uptick, as audiences spend more time gaming and artists look for new ways to play, with pop acts like Charlie XCX and Arlo Parks performing in gameplay becoming a common occurrence.

Lockdown is yet to make digital natives of us all. We are screen-weary, fun-starved. But I’ll say it here: Watch this space. We all remember our first really good gig – sweaty? Mosh-pit-y? I wonder if for today’s teens it’ll be characterised by pixels and a global audience. Yes, the future of virtual gigs may lack the atmosphere we know and love, but it is democratic, accessible, and probably, to some, feels just as hedonistic. Let’s reserve our judgement. For now… get me to the nearest pub.

Filed under: Music

Tagged with: audience, charli xcx, concert, fortnite, future, gig, instagram, live, live stream, minecraft, music, performance, travis scott, twitch, virtual

Comments