“You have to allow yourself pleasure as well as angst.” – In conversation with Susie MacMurray

September 15, 2020

Credit: Susie MacMurray

‘Murmur’, Susie MacMurray’s forthcoming exhibition at Pangolin London in October, is an exhibition of firsts. It is Pangolin London’s first physical exhibition since lockdown and it’s MacMurray’s first collaboration with Pangolin Editions, the foundry associated with the gallery. MacMurray is excited by how the collaboration has enabled her to develop her work, “My work has never really been that kind of work so it’s really exciting to have that opportunity and to have all those skills, and to have my mind stretched a bit with what I could do.”

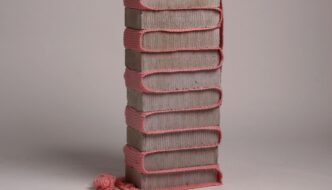

The result is a series of new bronze and silver works which she will exhibit alongside exquisite objects created in contrasting materials and drawings. ‘Medusa’, a large figurative piece produced in 2014, will become an addition to the Pangolin Sculpture Trail in Kings Place.

Although this was an opportunity to make sculptural pieces rather than the installation work which forms many of her commissions, during the site visit, MacMurray responded to the possibilities presented by a large expansive wall running the length of the gallery. “It did make me think, ‘What can I do with that wall?’ This (the installation, ‘Murmur’, after which the exhibition is named) came out of that and it was with that space in mind. It came out of the opportunity to use that as a huge drawing board.”

Her response is characteristic of MacMurray’s approach to her practice. Whether it is responding to a site for an installation or making large or small scale objects, “It’s a kind of juggling things together and it requires you to keep your peripheral vision open. If you get too ‘it’s about this or its going to be that’, you miss stuff.”

Credit: Susie MacMurray

Ostrich feathers, dipped in wax and suspended on fishhooks attached to piano wire, will sweep across the length of the gallery wall. The tension arising from not quite knowing how the installation will work in situ excites her, “What I’m hoping is when people come in you will see it from the side first and I think it will move. I’m really looking forward to seeing how it behaves. That’s part of the fun of doing these kinds of things and the fear because you really don’t know what it’s going to do until you’re there. You can’t rehearse it completely; it’s a calculated risk.”

The exhibition, ‘Murmur’, continues an exploration of the themes of fragility and courage, vulnerability and loss and the exploration of female identity, which dominates her work. Tension inherent in these themes plays out in MacMurray’s use of contrasting materials and the juxtaposition of impressive scale with the fragile nature of the elements that make a piece.

Although the exhibition had been commissioned before lockdown and much of the work was quite far on, lockdown placed the momentum on pause. Normality, whatever that is, was suddenly and irrevocably altered. MacMurray, like all of us, was left to resolve the feelings of being trapped and unable to see loved ones that surfaced. MacMurray used the opportunity to focus her mind and push her work further, creating work which may not have happened had she not had this hiatus. ‘Murmur’, emerged from this process of reflection.

“I started thinking about how I was sort of in the middle. I am a mother, but I am also a child. I was thinking about my relationship with my mother and children, about the feelings of letting them go. The piece, ‘Murmur’, is about taking flight and movement. The desire to break free and the fragility of it and the uncertainty of it and almost the joy and the fear in that. It just focused my mind in a more particular way on the things I am exploring anyway.”

Before she was an artist, MacMurray was a professional musician in the Halle Orchestra. Out of a personal crisis and a period of intense self-reflection, she made the transition to art carrying questions that continue to inform her practice and which she explores in both the work and the process of making the work.

Credit: Susie MacMurray

Smaller pieces in the exhibition, like ‘Clutch’, a nest constructed in sensuous, crimson velvet protecting smooth wax eggs out of which protrude fish hooks, suggest vulnerability and strength echoed in earlier works like ‘Widow’ (2009). ‘Widow’, made after the loss of her husband, is a garment sculpture made of leather and pierced with 100,000 two-inch dressmaking pins. From a distance, the piece shimmers, but as you get closer the element of danger becomes apparent. “I’m not denying the hard stuff or the danger, but also this power. I am trying to understand how to balance power and softness and how to be soft and kind and generous and good without being weak and vulnerable.”

‘Medusa’ (2014), like ‘Widow’, explores female identity. It is a powerful work, painstakingly made from copper chainmail, hand produced from copper wire. It is a contradiction of power and fragility which echoes MacMurray’s own feelings. “There is a definite sensuality about it. I want to be confident. I want to be comfortable in my body. I want to revel in it. I want to be like what the French feminist philosopher said about Medusa that she’s not screaming, she’s laughing and revelling in her sensuality and going, ‘Deal with it, guys. Tough, this is me.’ ”

“The figurative pieces are explorations of who I would like to be, who I would like to reassure myself of who I could be. It’s finding a balance between seduction and danger, vulnerability and strength, mortality and life. Through materials, the juxtaposition of things that have a little frisson with each other, have a conversation with each other and bring up that edginess and that energy that happens. I am trying to understand the crack in the middle that’s so tiny and you can’t see, that might explain everything. Which it never does. But it’s the process of asking. It’s the process of doing it that’s meaningful.”

The process of making is an extension of this enquiry. ‘Medusa’ was created over a period of eight months. MacMurray was aided by a group of young artists who came together to produce the chainmail from scratch using copper wire and literally stitched the sculpture together. “ I was thinking about it in terms of her mythology and I was also thinking about it in terms of the history of sculpture, how generally up until very recently bronze statuary on the whole has been very masculine, made by men, made of men, or if it’s of women it’s in the gaze of men. It tickles me enormously to think about subverting the process of making what looked, at first site, like bronze or a statue made of metal. It was literally made by a group of women sitting around like they were quilting or stitching and there was a sort fairy tale of exchange of knowledge and passing on of knowledge about the art world, or in any other time, fairy tales, cautionary tales and that sharing that goes on.”

“I used raw copper which will eventually tarnish and that was very purposeful in reference to her as a tarnished woman that had been raped. So, the materiality and the story and the process of making all intertwined into the meaning for me. It doesn’t matter whether anybody knows that, but it does somehow feel that the fact that it’s in there makes it stronger.”

Credit: Susie MacMurray

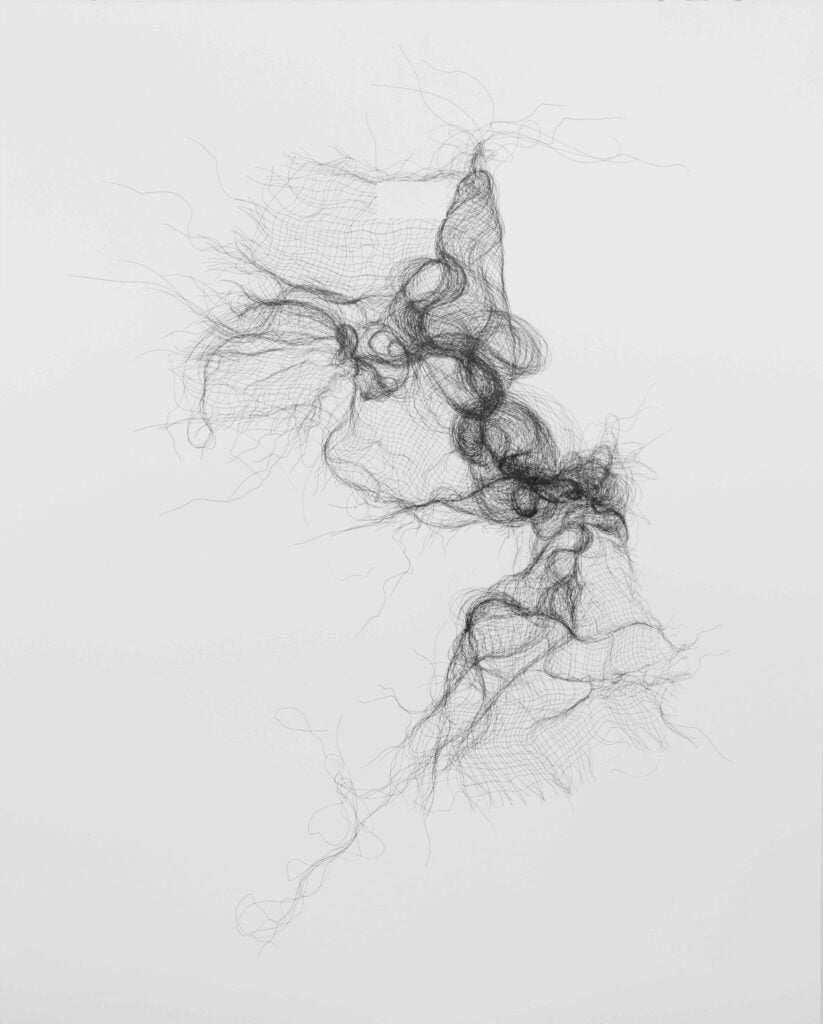

Alongside sculptures, MacMurray will show a series of drawings. They are intricate, delicate drawings of the materials she uses in her sculpture. MacMurray uses drawing as a meditative process to shut off the critical mind and tune into her creativity and spend time with the materials she uses. “It is thinking time. I solve problems unconsciously when I draw. I’m not pushing the boundaries of what drawing is in any way, but it is important. I’ve been responding to the feathers I’ve been using in small works. They’re a great pleasure to do and you have to allow yourself pleasure as well as angst.”

‘Murmur’ runs from 21 October – 22 December at Pangolin London in Kings Place. Find out more here.

Comments