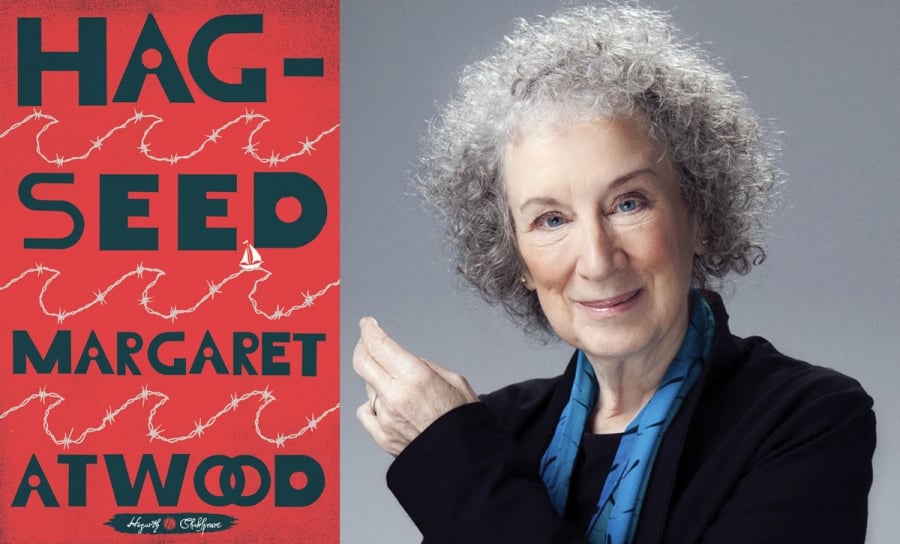

Canadian author Margaret Atwood joined writer and broadcaster Alex Clark at RNCM for Manchester Literature Festival this year. The event launched Hag-Seed, her new novel based on Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Hannah Gaunt tells us about the night’s proceedings.

After brief introductions and speeches of gratitude from the MLF directors, the main event was quickly underway. Margaret Atwood is something of a festival regular, but that fact did not seem to lessen the hushed anticipation which filled the auditorium as she moved to take her place on a comfortable looking armchair alongside Alex Clark, our interviewer for the evening.

Atwood is introduced with accolades. Hag-Seed, released this October, is her sixteenth published novel, the most recent of a notable body of work including numerous plays, pieces of short fiction, children’s books and poems: an impressive back catalogue. “You’re prolific”, says Clark. “Well, I am really old!” quips Atwood.

Those who have followed Atwood’s writing career (and at 76 years of age, perhaps not many of us can say we truly have) will be familiar with the author’s tendency to defy convention, to reinvent and to surprise. Hag-seed, Clark leads on, is yet another departure for the author. And this new novel certainly seems to fit that bill, as Atwood found herself exploring unfamiliar territory in order to participate in Vintage’s Hogarth Shakespeare initiative – a major new project reimagining the bard’s work for new audiences.

Writing for the project, she explains, was something that “sounded like a good idea” initially, but then soon became a much more complex task. Despite this, Atwood knew immediately that The Tempest was the play she wanted to retell – because it is “the closest Shakespeare comes to what he himself did every day; which was putting on plays”. When read through that lens – a play about writing plays is undoubtedly a well-made match for the author who penned the non-fiction work Negotiating with the dead: A writer on writing over a decade ago. Perhaps this long-standing interest in the motivations of writers is what stirred Atwood to take on the brief in the first place, seeing a unique opportunity to get under Shakespeare’s skin.

One of Shakespeare’s most acclaimed works, The Tempest tells the tale of a royal party and ship’s crew who find themselves on a desert island after a mysterious storm. The island is already inhabited by the usurped Duke of Milan, Prospero, and his daughter Miranda who have lived alone there for 12 years. Prospero is a practicing magician who has cunningly orchestrated the shipwreck and events that follow with the help of an island spirit named Ariel. He conspires to have revenge on his treacherous brother Antonio, and secure his daughter Miranda’s marriage into royalty. Literary scholars agree that Prospero’s magic intentionally alludes to theatrical illusion, and therefore his character can be seen to represent the role of a theatre director – or even Shakespeare himself.

Atwood reimagines the shipwrecked characters from Shakespeare’s original as inmates in a correctional facility in the 21st century. The characters are engaged in a rehabilitative literary programme, and readers join the story as they attempt to stage The Tempest themselves, under the guidance of Felix Phillips, our modern day Prospero. Rather than a betrayed Duke, Atwood’s Felix is the wronged ex-artistic director of a theatre festival, who is using his new teaching job with the prisoners to see out his wicked revenge on the rival who dared to cast him out.

When probed to explore the content further, Atwood is understandably reluctant to give away spoilers, but shares some insight into her thinking behind the updated characters and setting: “A shipwreck wouldn’t work in the modern day”, she explains, so instead a prison facility provided an interesting alternative space and set of characters on which Felix can work his ‘magic’. Ariel – a non-human character in the original, is reimagined as a convicted hacker in Hag-Seed, with handy skills and technical know-how to make the theatre director’s vision come to life. The character of Miranda presented a problem however: “In what situation would you see a man living with his teenage daughter, who has never seen another male?”. The solution was to give Felix a daughter who has already passed away, and then, in a clever twist, introduce a new female character in the form of a recruited actress brought in to play the ‘Miranda’ character in the inmates’ play.

A well-known difficulty with The Tempest is Prospero’s lengthy speech to Miranda detailing the character’s back-story for the theatre audience. It is an essential part of the play, providing the context for all that is to follow, but is nonetheless hard-going for actor and viewer alike. In her retelling, Atwood’s inmates decide to liven this section up by making it into a rap song – and, to our delight and amusement, Atwood and Clark perform this for us, rounding off the formal part of the event. If that comical and clever snippet is anything to go by, I am certain that Hag-Seed will not disappoint Margaret Atwood fans.

At this point in the event, appetite for the new novel sufficiently whetted, Clark turns to the audience for further questions. Atwood is asked about her intentions for Hag-Seed – is there a moral? Revenge is a key theme, she says – and forgiveness, but ultimately, “whatever a writer puts into a book and thinks of as the moral, it’s in the hands of the reader – the reader will decide”. Atwood skilfully springboards from these questions to touch on topics as wide ranging as utopias, politics, religion, and indeed the nature of writing – all of which she deftly explores with wit and insight.

Throughout the event she showcases a knowledge and appreciation for Shakespeare as well as many other great writers, and so it seems apt to return to one of them again to conclude:

“Writing a novel is liking walking through a dark room with a lantern which illuminates the things that were always there” – Virginia Woolf

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: female author, Hag-Seed, Manchester Literature Festival, Margaret Atwood, McrLitFest, MLF16, RNCM, Royal Northern College of Music, Shakespeare

Comments